The MassDOT is making plans to install a four-lane, 2,000-foot-long highway above the Charles River for the duration of a construction project that is anticipated to last a decade.

As the state highway agency prepares to file for permits for its “Allston Multimodal Project,” state officials are honing conceptual construction staging plans for the project’s most complicated segment: the so-called “throat” section where Soldiers Field Road, I-90, the Paul Dudley White bike path, the Worcester line commuter rail tracks, and the Grand Junction rail line all crowd through a narrow segment of riverbank behind the Boston University campus.

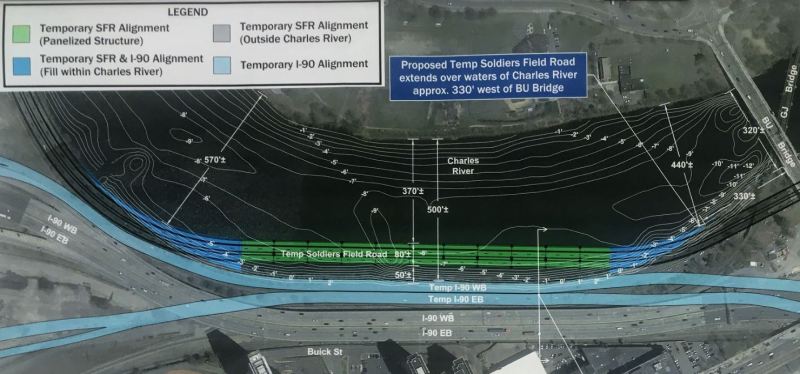

In order to make room for construction workers to relocate highway lanes and tear down the crumbling viaduct that carries I-90, project planners have proposed relocating the Soldiers Field Road and Paul Dudley White bike path to a “temporary” mid-river highway that would remain in place while the rest of the project is built.

In MassDOT’s proposed construction staging plan, contractors would begin the project by driving a wall of steel piles into the river to bury a half-mile length of Allston’s natural riverbank under “temporary” highways, which would then remain in place until the project’s final phase of construction, eight to ten years later:

The natural shoreline would be replaced with ~1/2 mile of metal sheet pile wall pic.twitter.com/q2KxUoXqQp

— People's Pike (@PeoplesPike) November 14, 2019

At an Allston Multimodal Project Task Force meeting last week to discuss these plans, Pallavi Mande, Director of Watershed Resilience for the Charles River Watershed Association, said that her organization is “not satisfied” with the agency’s construction plans.

Mande and other Task Force participants noted that MassDOT would need to clear a daunting number of permitting requirements under the Clean Water Act, the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, and the state’s Public Waterfront Act in order to move ahead with its plan.

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, for instance, states that waterways and wetlands like the Charles River may not be filled in if either “(1) a practicable alternative exists that is less damaging to the aquatic environment or (2) the nation’s waters would be significantly degraded.”

The construction contractors will also need to satisfy Section 402 of the Clean Water Act, which requires that the construction site “achieve specified Water Quality Standards” for any stormwater runoff that would end up in the Charles River.

Task Force participant Glen Berkowitz of A Better City observed that “this trestle bridge is likely to freeze more quickly in the winter than any other bridge” thanks to its lightweight, modular construction. “It’s going to require significant anti-icing treatment, to a degree that’s much greater than today’s Soldier’s Field Road.”

Project engineers acknowledged that any anti-icing chemicals deposited on the proposed bridge – along with other typical motor vehicle pollutants, like dust from tires and brake linings and leaking engine fluids – would wash off directly into the Charles River with little to no treatment.

“We think there’s a lot of room for improvement,” said Mande in a conversation near the end of the Task Force meeting. “I’m pretty confident they’ll figure out a better way to do this.”

MassDOT and federal agencies are taking public comment on the project’s environmental impact “scoping report” until December 12. Comments can be emailed to I-90Allston@dot.state.ma.us.