“If the increase continues, the time is not very distant when not to own and ride a bicycle will be a confession that one is not able-bodied, is exceptionally awkward, or is hopelessly belated.”

—“The Bicycle Festival,” July 13, 1895 New York Times

The bicycle came to San Francisco during the last quarter of the 19th century. Like other places, it first developed based on wooden wheels, similar to those that were bearing stagecoaches and being drawn by horses. Horse-drawn streetcars were the predominant mode of transit in the 1870s, peaking in the 1880s, at a time when the individual horse was also still a major source of personal transportation.

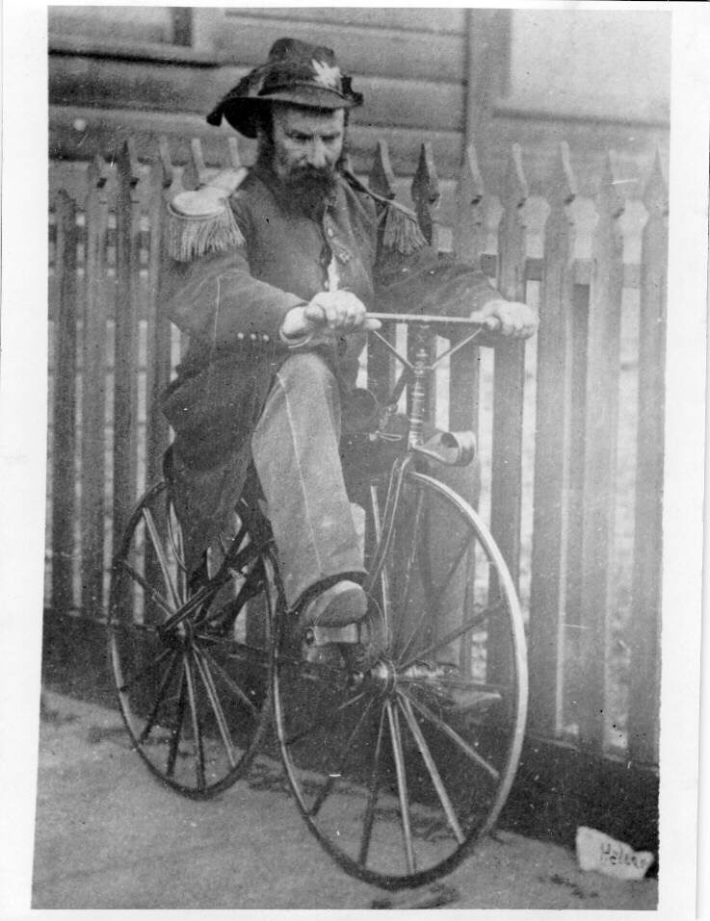

And then came the velocipede, an odd device that attracted some early adopters of the era. Here’s Emperor Norton, a fellow who was adept at self-marketing long before Facebook made it a basic survival skill!

The boneshakers were aptly named, running over heavily rutted streets on solid wooden wheels, eventually improved by coating the in solid rubber. The bicycle was not a transit option at that early stage, but a novelty, and a device that attracted the adventurous few who were ready to break with the limits of human powered locomotion. In “The Winged Heel” column in the San Francisco Chronicle of January 25, 1879, the writer fully grasps the possibilities:

“The bicycle ranks among those gifts of science to man, by which he is enabled to supplement his own puny powers with the exhaustic forces around him. He sits in the saddle, and all nature is but a four-footed beast to do his bidding. Why should he go a foot, while he can ride a mustang of steel, who knows his rider and never needs a lasso?.. The exhilaration of bicycling must be felt to be appreciated. With the wind singing in your ears, and the mind as well as body in a higher plane, there is an ecstasy of triumph over inertia, gravitation, and the other lazy ties that bind us. You are traveling! Not being traveled.”

(I have to admit a great appreciation for that last aphorism, echoing through time a later motto of Processed World magazine that I helped produce in the 1980s: Are you doing the processing? Or are you being processed?)

The second club nationally and the first on the west coast was the San Francisco Bicycle Club, founded on December 13, 1876. They petitioned the Park Commission for permission to ride their new-fangled devices in Golden Gate Park. Overcoming their astonishment that there was actually a club for wheelmen, the park commissioners allowed them to “enter Golden Gate Park at the Stanyan Street entrance to the South Drive before 7 a.m. only.” Intensive self-policing kept the wheelmen within the bounds of the concession, and before too long the “privileges were extended.” (“When San Francisco Was Teaching America to Ride a Bicycle,” by Ida L. Howard, San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 26, 1905) But it was in the next decade that bicycling began its precipitous take-off.

“The Bay City Wheelmen [founded in 1884] was the first competition for the SF Bicycle Club. It raised enthusiasm to the highest pitch. Each man was eager to find opportunities for the keenest rivalry, for the honor of his club was at stake, and in those days wheeling was a clean sport. Sport for the true love of sport. There were none of the sordid motives which follow in the train of professionalism. To become a professional was to place one’s self outside of the social pale.”

The explosion of bicycling is easily traced in the production statistics over a scant ten years, from 1885 to 1895. Where six factories produced about 11,000 bicycles in 1885, there were 126 factories in the U.S. producing a half million bikes ten years later. (SF Chronicle, May 12, 1895)

The bike clubs organized century rides around the Bay Area and annual “Bike Meets” where the fastest cyclists would compete against each other before large audiences. One of the biggest ever was during the 4th of July weekend in 1893 when an estimated 20,000 spectators would jam a special track built at Central Park just south of City Hall to watch the scorchers as they hurtled around the loop.

Generally absent from most accounts of the bicycling boom in the 1890s is a closer look at the key ingredient that made it possible: rubber. Rubber was the magic ingredient that altered the transportation landscape, but not before it had already become an essential ingredient to much of the newly industrializing world. In his excellent book, The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power, and the Seeds of Empire (Penguin: 2008), historian Joe Jackson describes the Rubber Age:

[During the 1860s] rubber had become essential for war. In addition to its many uses in railroads and steam engines, military catalogues of the era show new designs using rubber for shoes and boots, blankets, hats, coats, pontoon boats, bayonet guards, tents, ground sheets, canteens, powder flasks, haversacks, and buttons. Rubberized silk was used for military balloons. War also created a boom in reconstructive surgery using hard rubber teeth, nose pieces, and custom-molded prosthetics.

Jackson continues a hundred pages later:

The 1890s would be the decade of the bicycle. The seven million bicycles found worldwide in 1895 used most of the world’s rubber, a boom that would not have occurred if not for the invention of the “pneumatic rubber tyre.” Although there had been bicycles previously, they rode on solid rubber tires. These were puncture-resistant, a boom on roads where nails were frequently shed from horseshoes, but they lacked suspension, were hard to steer, and were an unpleasant ride. This changed by the late 1890s. The market was flooded with steel tubes, ball bearings, variable speed gears, and high-quality chains. Above all else, it was flooded with replaceable rubber tires and inner tubes, mass-produced in the factories of Dunlop in Birmingham, England; Michelin in Clermont-Ferrand, France; and Pirelli in Milan, Italy. The bicycle was cheap and popular. People suddenly had a means of freedom that had been unknown.

But where did this rubber come from? Synthetic rubber was not developed until WWI. Before that it was derived entirely from several species of latex-sweating trees, the finest of which was Hevea, found scattered throughout the Amazon. Two major regions of the world were permanently altered in the frenzied pursuit of rubber supplies: Amazonia and the Congo. In both cases, an extreme brutality was used, mutilating and murdering literally millions of people to produce the precious rubber, the whole process lashed by the rising demand in the U.S., Europe, and Japan created by the bicycling boom.

Five major tire and rubber companies emerged in the three decades after 1870, the three mentioned above and Goodyear and Goodrich in the U.S. North American rubber imports jumped from 8,109 tons in 1880 to 15,336 in 1890. From 1875 to 1900, the U.S. consumed half of all the rubber produced in the world. What was happening at the point of production? Joe Jackson spares us little in his description:

During the fifteen years of Belgian King Leopold’s stewardship, the population of the Congo Free State dropped from 25 million to 10 million—15 million dead for approximately 75,000 tons of rubber. That equaled one life per every 5 kilograms. In 1907, similar evils came to light on the Upper Amazon. The Putamayo is a vast area around a river of the same name, which runs through territory that was disputed between Peru and Colombia; the river joins the Amazon near the western border of Brazil… Slavers rounded up entire tribes and forced them to work on rubber plantations… Rubber baron Julio Cesar Araña’s company “systematically employed terror and torture against it native work force for higher profits. The Indians were beaten, mutilated, tortured, and killed as punishment for “laziness” or the amusement of bored overseers. Women and girls were raped, the elderly were killed when they could no longer work, and children’s brains were bashed out against trees. Morever, Araña registered his Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company in London, thus linking Britian, the world’s leading antislavery nation, with a firm that was enslaving Indians… Araña had manipulated the British cult of free trade like a maestro, equipping his company with a tame set of British directors who allowed easy access to London funding… The Huitoto, Boras, Andokes, and Ocainas were flogged till their bones showed. They were denied medical treatment, left to die, then eaten by the company’s dogs. They were castrated. They were tortured by fire by water, by being tied head-down, and by crucifixion. Their ears, fingers, arms, and legs were lopped off with machetes. Managers used them for target practice and set them afire with kerosene on the Saturday before Easter as human fireworks for the Saturday of Glory. Whole tribal groups were exterminated if they failed to produce sufficient rubber. Julio Araña’s peak production of 1.42 million pounds of smoked Putamayo rubber cost thirty thousand lives.

Meanwhile, bicycling was being embraced by women in unprecedented numbers, as many saw the device as their best means for at least a partial self-emancipation. Women’s clothing was changing, and social mores were too. In “Thousands Ride the Noiseless Bicycle,” in the San Francisco Chronicle (May 19, 1895), the shift is described:

In the Park the other day, out of forty wheelmen, thirty-five were appropriately dressed in knickerbockers of some sort, short coats and caps. It is the same way with women. The long skirt is being pretty generally discarded, and if a woman cannot wear either bloomers or a short skirt she might as well keep off the wheel… People used to ride only for pleasure. Now they ride instead of taking the cars, and own wheels instead of feeding horses and washing carriages. Doctors use the silent and inexpensive steed very extensively in making professional calls. For night calls it is always ready, and there is a considerable saving in hack hire, livery stable fees and coachman’s wages. The keepers of livery stables say the bicycle has cut into their business far more seriously than electric cars ever did.

A well-known riding teacher says that most of his women pupils take their first lessons in skirts on a woman’s wheel. They go out on the road this way from three to ten times. They they come back to him in bloomers, learn to mount and dismount from a man’s wheel, which is a great deal harder than the other way, and never again can be induced to ride a woman’s wheel. Girls who ride for pleasure like to ride with men, of course, and the only way to do it is to keep the pace they set. It cannot be done in skirts on a woman’s wheel, and a man, even a polite escort, cannot be expected to ride slow forever, and so it happens that men’s wheels grow more popular with women every day, and after awhile when people stop talking about it and the small boy stop hooting it will all be very charming and agreeable.

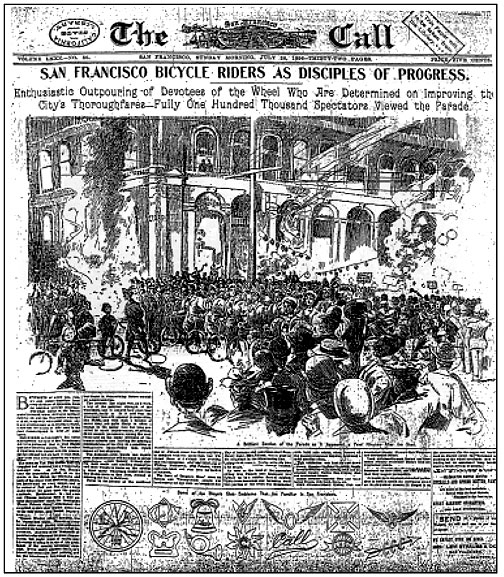

The mass of cyclists in San Francisco were not narrowly focused on bicycling alone. They became the backbone of a broad movement for improved streets and “Good Roads.” On July 25, 1896, thousands of cyclists filled the streets in the largest demonstration seen in the City’s history. Hank Chapot wrote a great article (pdf) about the Great Bicycle Protests of 1896, and here’s a brief excerpt:

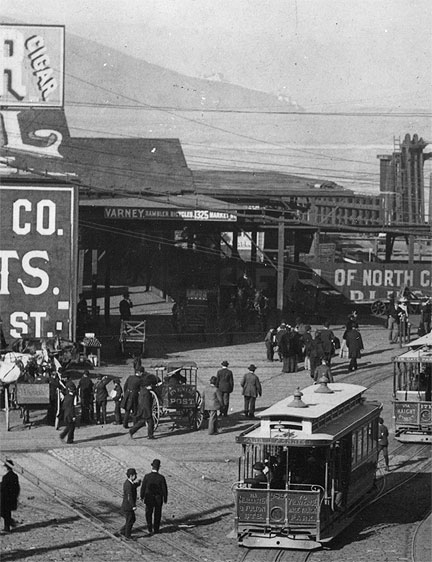

San Francisco, though the third wealthiest city in the nation, was an aging boomtown. Streets were muddyor dusty, full of horseshit, and increasingly crisscrossed with a hodgepodge of streetcar tracks and cable slots, creating an unpredictable, hazardous mess. The city’s old dirt roads and cobblestone thoroughfares were originally laid down for a village of 40,000 were now serving a metropolis of 360,000.

On Saturday July 25th of 1896, after months of organizing by cyclists and good roads advocates, residents took to the streets in downtown San Francisco, inspired by the possibilities of the nation’s wonderful new machine, the bicycle. Enjoyed by perhaps 100,000 spectators, the parade ended in unanimously approved resolutions in favor of good roads, and a near riot at Kearny and Market.

A five-year wheelman named McGuire, speaking for the South Side Improvement Club stated: “The purpose for the march is three-fold; to show our strength, to celebrate the paving of Folsom Street and to protest against the conditions of San Francisco pavement in general and of Market Street in particular. If the united press of this city decides that Market Street must be repaved, it will be done in a year.” Asked if southsiders were offended that the grandstand would be north of Market, McGuire exclaimed, “Offended! No! We want the north side to be waked up.We south of Market folks are lively enough, but you people over the line are deader than Pharaoh!”

So as we continue to ride in a new bicycling renaissance in San Francisco more than a century later, we can take inspiration and lessons from our predecessors. A citywide system of dedicated bikeways is long overdue. Imagine how many would ride if there were safe thoroughfares to bicycle on that would make it the most pleasant and most direct way to get from anywhere in the city to anywhere else? Point A to point B, smelling the flowers, the clean air, hearing the birds, and enjoying your friends and neighbors… why not?

“When you have attained a proficiency which enables you to take out your handkerchief, wipe your nose and replace the mouchoir in your pocket without slackening your pace, you have fairly graduated… For fun there is nothing like cycling, and before many years two or three family wheels will be as much a part of the ménage as the modern range and sewing machine are now.”—San Francisco Chronicle, 1896