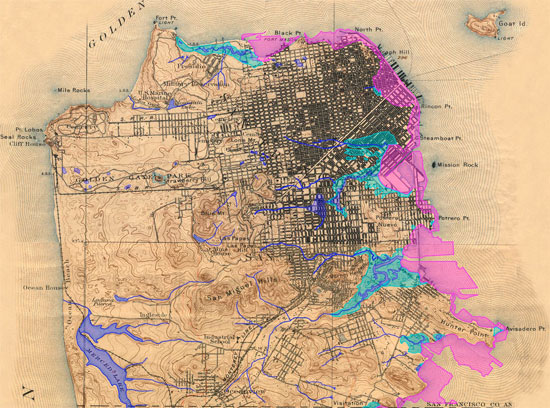

The Mission is more than just a meeting point for different cultures: it's also a meeting point for different waters.

Hundreds of years ago, two water sources converged along what is now Folsom Street. During rainy season, fresh water flowed east down from Twin Peaks, aligning roughly with today's 14th and 18th Streets. Those streams met at what was once a salty tidal estuary, and is today home to warehouses and lofts. That estuary waxed and waned with the tides, filling with bay water at times deep enough to float a boat, and then draining to be little more than a sticky mudflat.

Settlers saw an advantage to the watershed's layout: cows and people drank the freshwater, and deposited their waste in the daily flush of the estuary.

Though it was unsanitary and untenable for a growing population's needs, the echoes of San Francisco earliest sanitation system can still be found in today's sewers.

"In order to understand the sewers of San Francisco, you have to be a historian," said Greg Braswell, an expert on San Fransico's sanitation facilities, during a recent sewer tour called Fathoming.

The workshop and bike tour were organized by Workspace artist Miles Epstein, whose interest was piqued a year ago when the facility was flooded during heavy rains. Epstein, local water historian (and Thinkwalks tour guru) Joel Pomerantz, artist and geologist Judy West, and Braswell combined their unique knowledge to illustrate some of the more interesting parts of the current and historical system.

On the tour, Braswell and the others explained that as the settlement around the Mission and Potero Hill grew, pollution in the estuary became unbearable. Early experiments with wooden box sewers were a failure, unintentionally creating highly fertile, highly unsanitary compost chambers. The first brick sewers appeared from the 1860s through the 1880s, in a hodge-podge that emptied into creeks and marshes that smelled worse and worse over time.

Finally in the 1890s, Carl Edward Grunsky developed plans for an innovative gravity-based sewer that would carry waste all the way to North Point, where the rapid current would sweep it out to the Golden Gate, or back towards Oakland, depending on the time of day. It took years before the city built the pipeline, finally realized during the construction boom after the 1906 quake and silver industry lulls during which there was an excess of unemployed miners.

That pipeline is still in place today, draining all the way from Daly City. It was a giant leap forward in sanitation, which persisted unchanged for decades, despite clear problems. For example, the system couldn't handle large storms and during moderate rain and about sixty times a year it would overflow and dump raw sewage into the bay. Though it would seem terrible to us today to have so many overflows, this was consistent with most cities' practices up until the 1950s.

In 1972, the Clean Water Act changed everything. San Francisco was the first city to experience an EPA enforcement action, which was all due to sewage. "They said, 'you gotta stop pooping in the bay,'" Braswell explained.

Modifying the sewer system would be expensive and the city initially balked. Ultimately, with significant state and federal assistance, a ring of underground chambers was built around the city. Those chambers function like waiting rooms, detaining stormwater until the treatment plants have time to process it all. They're massive, some as big as 25 feet wide by 45 feet tall.

Today, overflows are significantly decreased. On average, the city issues around seven per year off the coast from Ocean Beach, four along North Point, ten into Mission and Islais Channels, and one near Yosemite Slough.

A Bikes's Eye View of the Sewer

The bike tour portion of Fathoming took us to several points of interest, both to the creek system and to the sewer that followed.

The first stop was an unassuming street corner at 19th and San Carlos. Against the backdrop of a windowless PG&E substation, Pomerantz explained that the intersection was once the site of a gully that anchored a marshy resort called The Willows. For several years in the 1800s, The Willows was a rural getaway from the hustle and bustle of "urban" San Francisco, which at that time was a cluster of buildings in what we now know as the Financial District.

At that time, it was about the thirty foot drop into the mud flats. That change in elevation has since been smoothed over with fill and construction debris, often for use as farmland or to reduce the marshy smell.

The next stop was at Shotwell and 17th, another topographic low point. During major storms, Braswell explained, nearby sewers will fill to capacity. At that point, the streets become "emergency relief valves" -- as we graphically witnessed last year -- and the water flows down 18th into a pump station that forces the water back into the sewer. It's not an ideal design, but it's been the most cost-effective for the city for over a century. In 1899, Grusky predicted that developers' low grading would cause flooding to plague the neighborhood, and he was right.

The tour continued down Harrison Street to a wasteland between the ASPCA and Best Buy. That's the point in the system where the sewer lines are the closest to the street, about a foot and a half below the asphalt. There's a brick weir -- a high wall -- in the tunnels at that point, which forces water to North Point under normal conditions and allows drainage to detention basins during wet weather.

"This is ground zero," Braswell said, referring to the convergence of natural historical waterways, sewer systems, and the still-present railroad tracks that once guided trains through the heart of the Mission, almost reaching what we now know as AT&T Park.

From there, the bike tour moved to the traffic circle near the Pacific Design Center, where Kansas and 8th Streets meet. Before there were streets, that traffic circle was likely an island in the middle of Mission Creek. That's another "ground zero" area, the point at which the railroad once marked the southern edge of San Francisco, where the street grid curves and where the street blends nebulously between Treat, Division, and 13th.

Following the creek east, the tour stopped at the piquant pump station at the end of Mission Creek Channel, the only remnant of the once-massive Mission Bay. There, during heavy rain, as much as 100 million gallons a day is pumped to the water treatment plant in the Bayview. And when that system gets overloaded, then gates open and waste is dumped directly into the channel.

The final stop was a tiny paved lot near ... well, not really near anything right now. To the north, Mission Rock once jutted into the bay, but it was blown up long ago. To the south, duck tours plunge off of a pier into the water. Across the street are the brand new UCSF buildings, empty and abandoned on weekends.

Gradually, the land along the bay will become parkland over the next few years. For now, there's a kiosk with Judy-West-designed maps of nearby historical elements, anticipating that future greening.

One of the most significant existing landmarks in the area is under the water: when a bike messenger dies, a ghost ride proceeds to the pier and tosses the messenger's bike into the bay.

The Future of Water

San Francisco has dug itself into a bit of a hole with its current sewer system. Though it works relatively well most of the time, upgrades are needed to improve safety and efficiency, and to replace crumbling brick pipes. On the positive side, those construction projects may present an opportunity to see improvements above ground.

For years, Judy West has campaigned to transform the historical creek alignment into a bikeway. Treat follows the old alignment of the railroad, cutting diagonally through the Mission to Best Buy, where it becomes Division and heads east to the waterfront. The proposed bikeway would roughly mimic the flow of what's commonly called Mission Creek, the combination of the tidal estuary and its small freshwater tributaries.

"It's a fifty-foot-wide swath of land that follows the sewer. I've been trying to push the city to utilize this right-of-way," said West. "There's a lot of underutilized land along this corridor, which is basically the natural drainage system."

As luck would have it, that's just where the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, which manages the sewer, may need to tear up the street for improvements.

"Money for bike improvements is kind of limited," West said. "It might be sewer improvements that make it green."

It wouldn't be the first time that sewage construction results in improvements to public space. A mural at 16th and Harrison marks the former location of a bridge on 16th Street that spanned Mission Creek. In Visitacion Valley, Leland Avenue's new bioswales reduce stormwater runoff.

The area that was once Mission Creek is rife with opportunities for green upgrades. A gravel yard near Mission Bay, abandoned rail lines that still lie in the street near Rainbow Grocery, and wide-open pavement alongside the freeway could all benefit from plantings and pocket parks.

But for now, the neighborhood is little more than an elevated freeway and lifeless intersections. Not quite the Mission, not quite SOMA, not quite Mission Bay, not quite Potero Hill, it's a ghost-corridor in what was once a gateway to our earliest outposts, now obscured both by history and the ground beneath our feet.