In parts of San Mateo County, a quiet street with a bike lane can abruptly lead a bicyclist onto a dangerous six-lane traffic sewer with no bike infrastructure or wayfinding signs. Pedaling over a highway overpass or traveling to and from Caltrain can also be a daunting trip.

"You find stretches where it's good and then you get to the next stretch that's good and there's a life or death connector," said John Murphy, a longtime bicycle commuter who rides through San Mateo County to his job in the South Bay. He said there are comfortable points on the county road in San Carlos and Belmont that run adjacent to the rail tracks, "but if your job is on the other side of the 101 freeway there's no way to get across without kind of taking your life into your hands."

The scattered and incomplete 246-mile network of on-street bike routes and off-street paths that stretch across the region's 21 cities, according to advocates, reflects a decade of poor funding and stagnant political will to make a region dominated by auto travel inviting to bicyclists.

"There's this perception in San Mateo County that there's not a lot of cyclists and it's one of those kind of vicious circles of 'well, there's not a lot of infrastructure so there's not a lot of cyclists,'" said Caryl Gay, a Peninsula advocate for the Silicon Valley Bike Coalition (SVBC). "The people you tend to see out there are the die hard people who don't really care that there's no infrastructure. But there are a lot of people who I talk to that say 'oh it's really great you bike, I would love to if only it were safer.'"

"It's got fabulous potential," said Jean Fraser, Chief of the San Mateo County Health System and a daily bicycle and Caltrain commuter. "It's mostly flat and the weather's great most of the time and many of the streets are very calm but it is very spotty."

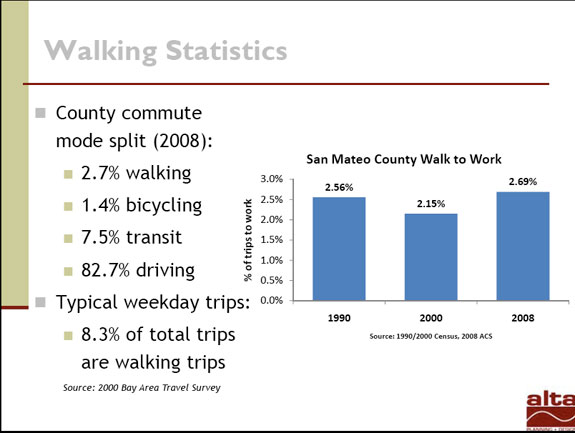

According to census figures outlined in a report [pdf] prepared by Alta Planning and Design, only 1.4 percent of San Mateo County's 718,000 residents ride their bikes to work. That figure does not include bike commuters who live outside San Mateo County and may also take Caltrain.

San Mateo County's regional government association, C/CAG, adopted a bike plan in 2000 but less than half of the 334 miles of planned bike routes have been installed, according to Alta.

"There's no real drive in the county to do too much," said Steve Vanderlip, who used to work on behalf of the SVBC before starting Bike San Mateo County a few years ago. "The county plan is a good example. It just kind of sits there because the cities don't have to do it, the county can't make them do it and there's not much enthusiasm among the cities to do a lot."

"The problem with advocating on the Peninsula is that you have to approach all these different cities, which means that you have to have a good network of advocates and a good rapport with the public works directors," said bike advocate Pat Giorni, who along with Vanderlip used to sit on the Peninsula SVBC committee.

A New County Bicycle Plan

Some progress could be on the horizon, though. For the first time in more than a decade, C/CAG is working on updating its bike plan and is also tacking on a pedestrian component. The draft plan, according to C/CAG project manager John Hoang, calls for adding 246 miles of on-street bike routes and 50 miles of off-street paths. He could not say how many miles of the on-street routes would be Class II bike lanes, as opposed to Class III bike routes that only have signs or sharrows. A map of the proposed routes is being presented at a public workshop tonight.

"We would like to see much better east-west connections, particularly across the (101) freeway, because that's really the choke point and is really difficult for a lot of cyclists," said Corinne Winter, the executive director of the SVBC. "There are a lot of people who won't bike simply because the freeway presents a barrier. So, in terms of big projects, putting in more bike and pedestrian bridges or modifying the existing overpasses to accommodate bikes and pedestrians is definitely our top priority."

Last December, a 68-year-old Palo Alto man was killed while he was pedaling over the six-lane Hillsdale Boulevard overpass. Vanderlip said he and other advocates have been reviewing existing overpass conditions [pdf] and hoped to "identify and work toward some improvements." It took a few years, he said, to get bike lanes and a fence installed on the north side of 19th Avenue over Highway 101.

"The chain link fence was required by Caltrans to allow a bike lane to be placed. Maybe they figured bicyclists were more likely to fly over the old low railing if a bike lane is installed," he said.

The process has also been complicated by jurisdictional issues with Caltrans, an agency that is focused mostly on moving automobiles and very slow to act on bike and pedestrian facilities. It owns the right-of-way on many routes and bike advocates would like to see a change so that their projects can be prioritized. One example is El Camino Real, a north-south corridor and high-volume state highway that has the highest rate of crashes involving bicyclists and pedestrians in San Mateo County. Although El Camino Real is an official bike route, it doesn't have a single bike lane. That could change under the Grand Boulevard Initiative, which calls for better bicycle and pedestrian amenities along El Camino Real from Daly City to San Jose.

"I feel like we haven't really focused very well on trying to think about how people (who bike) move through the Peninsula," said the SVBC's Gay. "We have one main north-south route, but I think there should be many more than just one. There are people who live in the hills, on the east side of the freeway, and I don't think we're really there yet in terms of thinking how we can move people by bike over longer distances."

Vanderlip crafted some recommendations [pdf] to C/CAG and hoped that the agency's Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (BPAC), which makes funding recommendations for bike projects countywide, would seriously consider them before updating the San Mateo County Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan.

Some cities are also in the process of developing bike plans, including South San Francisco, Redwood City, Menlo Park and Pacifica. Winter of the SVBC said what is really needed is a countywide bicycle coordinator, who could either work for C/CAG, the county government or even under the San Mateo County Health System.

"I think that the reason that San Mateo County is lagging behind a number of Bay Area counties in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure is because there has not been a county bicycle/pedestrian coordinator with the staff of any of the agencies at the county level who is able to coordinate getting good funding," she said.

Pedestrian Improvements

Funding has also been scarce for pedestrian improvements. Pedestrian deficiencies, according to Alta, include disconnected streets, missing connections, physical barriers and major streets that have few crossing opportunities. Fehr and Peers, a transportation design firm, has been hired to develop the pedestrian plan, which will be especially important for the county's growing senior population. By 2030, the region's total population is expected to grow by 14 percent, including a 72 percent increase in the number of people over 65 and a 150 percent rise of seniors over 85.

"Many of the diseases, conditions and effects of old age can be really mitigated by exercise. So, exercise not only helps the body it helps the mind. From a public health perspective, with an aging population, it's even more critical to have a wonderful pedestrian environment," said Fraser.

The proposed policy framework [pdf], which is supposed to define C/CAG's role in developing and implementing the plan, sounds promising. The vision statement sees a future when:

San Mateo County has an interconnected system of safe, convenient and universally accessible bicycle and pedestrian facilities, for both transportation and recreation. These facilities provide access to jobs, homes, schools, transit, shopping, community facilities, parks and regional trails throughout the county. At the same time, the county has strengthened its network of vibrant, higher-density, mixed-use and transit-accessible communities, which enable people to meet their daily needs without access to a car.

Although many advocates are glad to see the county update its plan, they remained skeptical that it would be enough to cause a significant mode shift and said it is complicated by the fact that many people who sit on government bodies making funding and policy decisions are mostly drivers not bicyclists.

"I feel like they're making incremental improvements and I think, especially when you think about a plan that could last us another 10 years, we need to be thinking visionary," said Gay. "And so we have to ask ourselves, 'what do we actually want the bike infrastructure to look like in 2020?' It's going to be here before we know it."

She added: "I feel like if we don't have the vision of what it could be we're never going to reach it."

A map of the proposed routes will be presented tonight at the only public workshop that will be held on the San Mateo County Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan. The two-hour meeting begins at 6 p.m. in the 2nd floor auditorium of the SamTrans building at 1250 San Carlos Avenue in San Carlos. If you can't make that meeting, advocates say it's still very important to submit written comments.