Disappointed proponents of the thwarted Cesar Chavez East plan for a road diet between Kansas and Evans were at least spared the temptation of using cliché after a contentious meeting on June 27. They couldn’t say the city was throwing bicyclists and pedestrians under the bus because there is no bus.

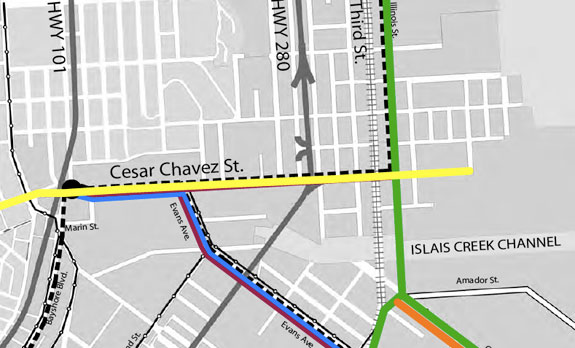

Past Bryant Street, where the 27 turns north toward downtown, travelers heading for points east can choose to hoof it through a nasty freeway interchange, cycle on a glass-strewn path and share a lane with a truck, or drive. But they can’t choose public transit unless they want to go way out of their way and take multiple routes, even then perhaps being left off blocks from their destination. Missing in action Muni completes the area’s trifecta of unsafe or nonexistent sidewalks and lack of bike lanes. Together, these factors make what could be a short, easy distance feel like the other side of the moon.

Meanwhile, the Bayview Transportation Improvements Project, which provided cover for the city’s decision to crush plans to make bicycle and pedestrian improvements along eastern Cesar Chavez, barely mentions Muni. The only reference on its website is a promise for smooth service along the T-Third line by rerouting trucks. The real purpose of the project is clear, as spelled out in its FAQ:

“Q: What is the purpose of this project?

“A: The purpose of the project is to: (1) develop a more direct auto and truck route between U.S. Highway 101 and the redeveloped Hunters Point Shipyard and to the South Basin industrial area; and (2) reduce through truck traffic on Third Street and residential streets in the Bayview.”

Trucks dominated the discussion at the June 27 meeting that put the kibosh on a proposed road diet from four to three vehicular lanes to make room for bike lanes and sidewalk improvements, putting proponents in a tricky spot. No one wants to inhibit industrial uses that provide necessary services and good jobs, and the possibility that increased congestion could worsen air quality in the residential neighborhoods bordering the project has alarmed Bayview residents justly wary of any moves that could dump more pollutants on them. Proponents who fail to deal with these issues could come across as caring more about their bike lanes than a childhood asthma epidemic.

But what has gotten lost in this messy discussion is the role of public transit and the potential for a more comprehensive transportation demand management approach that could help truck traffic flow more smoothly while still allowing space for bicycle and pedestrian improvements. San Francisco General Hospital, facing transportation chaos in 2009 as several years of hospital rebuild construction loomed, held a transportation fair, conducted employee surveys, installed NextBus in lobbies, and educated workers about Commuter Check and Emergency Ride Home programs. SFGH has succeeded in steadily reducing the percentage of drive-alone commuters, even in the face of medical workers’ crazy hours. A survey of current workers along Cesar Chavez could provide crucial information about alternatives to driving to work every day. Why can’t the city proactively target individual drivers to get cars out of the way of the needed trucks so pedestrians and cyclists can claim some space?

Also lost at the June 27 meeting were a few contradictions in the case made by the Mayor’s Office and the Port. A slide [pdf] showing the planned development that allegedly necessitates the retention of four truck lanes on Cesar Chavez features mostly housing and mixed use, plus the new 49ers stadium, not new industrial uses. So are four lanes of traffic really being reserved because we need to support the city’s industrial base, or are they being kept because new residents will likely be more upscale and more likely to drive than current residents? These new residents will also be very unlikely to work on Cesar Chavez. People working there now already need a way to travel on foot, bicycle, or bus.

When the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency conducted a meeting June 15 about the construction of a new Muni maintenance facility on Cesar Chavez between Indiana and 280, a few of us from CC Puede took the opportunity to point out the lack of east-west Muni service for that site and to ask if the SFMTA had any plans to implement new routes so that Muni workers could actually commute on Muni. The response was “we’ll get back to you,” and SFMTA did get back to me.

According to a letter from Jay Lu, Public Relations Officer, dated June 28, “From 2007 to 2008, the SFMTA conducted an evaluation of its existing service as part of the Transit Effectiveness Project [TEP]. At that time, the SFMTA considered additional transit service on Cesar Chavez. However, service changes were not recommended "because of more pressing needs throughout the system.”

Perhaps one of those more pressing needs was the Culture Bus, the $7 a ride vanity ride that ran from September 2008 to August 2009, lost over half a million dollars in four months, and served basically no one.

When CC Puede members spoke up for the implementation of an east-west Muni line down Cesar Chavez during the TEP process, we were told “the numbers aren’t there.” No explanation was offered for how those numbers were crunched. Did the small light industrial workplaces that line eastern Cesar Chavez get a chance to say if workers there would ride a Muni line if it existed? Of course, numbers would indicate low ridership along a street that has no bus.

SFMTA’s thick-headed response to requests for east-west service has at times verged on parody. At one TEP meeting, I tried to explain the need by walking the Muni rep standing by a large map display poster through the difficulties of the hairball, pointing out where you have malfunctioning crossing lights, where you have to run across a freeway ramp, and so on, the point being that no one would have to walk through this mess if a bus could take them to their destinations safely. His response, “So it’s a pedestrian issue then?”

As mentioned, one reason given for the need to retain four lanes of traffic for vehicles on this same stretch of eastern Cesar Chavez is future plans for new housing, retail, and mixed uses in the southeastern part of the city. The sluggish TEP response to a current need for transit versus the energetic defense of vehicular space potentially needed for plans still on the drawing board—in some cases, still in court—exposes the city’s priorities. Trucking companies like Recology have political juice. Workers at small light industry, and even a larger company like Veritable Vegetable on Cesar Chavez and Tennesse, get less attention.

Peggy da Silva of Veritable Vegetable also spoke up at the June 15 SFMTA meeting, after we were initially told that Muni service was already fine. Since she works right there, she was able to call the SFMTA on that claim. In a subsequent letter in response to a hearing specifically about the T, da Silva wrote:

“We are very dissatisfied with the T line. We have 130 staff people and operate 7 days a week, 24 hours a day. It is very difficult for our staff people who have to arrive early in the morning or leave our business late at night. Even at ‘peak’ times, the service is slow.”

Da Silva has spoken up repeatedly for Veritable Vegetable’s many staff people who live in the Mission and would be well served by an east-west Muni line along Cesar Chavez. “One of the reasons we are such strong advocates of pedestrian and bicycle improvements is that Muni does not serve our workplace well,” she said in an e-mail after the June 27 meeting. “Infrequent, unreliable service, and not available 24 hours a day. Therefore, our staff people need to be able to walk and bike safely.”

Veritable Vegetable isn’t the only large employer along the Muni-less eastern Cesar Chavez. The Muni maintenance facility under construction will have about 150 workers around the clock. The Department of Public Works already operates a large maintenance yard near Kansas Street.

The area of Cesar Chavez in question runs between two freeways: 101 and 280. Freeways already function as gated communities for private vehicles, with a few express buses that make no stops along the freeway (as opposed to, say, Golden Gate Transit). The indifference of the Mayor’s Office and the Port to issues of inaccessibility extends the gated community concept to streets that connect to freeways, making them essentially off-limits as well to cyclists, pedestrians, and transit users in the interest of smooth vehicular traffic flow.

The ongoing plan described by the city to reroute trucks could provide a real service to the Bayview community if it does indeed improve air quality in residential areas. But the focus seems to be mostly on getting trucks off Third Street, reawakening concerns that the T line is more an instrument of gentrification than a community service. Mission Bay at one end may fill new housing with physicians at the other end, and god forbid these new Bayview/Hunters Point residents have to get stuck behind a truck on their drive to work. How the city addresses transit needs reflects its respect for users, and so far workers and travelers along eastern Cesar Chavez have gotten no respect at all.