San Francisco’s many auto repair shops are mostly concentrated along its motor traffic sewers, but when they’re placed without restriction in the thick of restaurants, shops, and pedestrian traffic, can they hinder our city’s most valuable streets as desirable places to be?

“Auto repair shops, and other auto-oriented uses like parking and gas stations, can degrade the pedestrian environment in neighborhoods,” said Tom Radulovich, the director of Livable City.

On Ninth Avenue in the Inner Sunset, one of the city’s many commercial streets, three repair shops sit in the mix of residences, shops and restaurants. Street life is plentiful on the stretch, but the space around the large auto shop between Irving and Judah streets in particular appears empty. Shelby, a resident of the neighborhood, was enjoying a snack outside Arizmendi Bakery a few doors down.

“Randomly, you’ll have a little strip of small restaurants and art galleries, but then you’ll have places like that that don’t seem to fit in because they just got there first,” said Shelby. She also pointed out that many vehicles pulling in and out of some garages, and the illegal parking they attract, can hinder and endanger passersby.

“It sucks as a bicyclist when you’re trying to go up a hill or something and there are three cars double parked,” she said. Cars left on the sidewalk aren’t an uncommon sight, either.

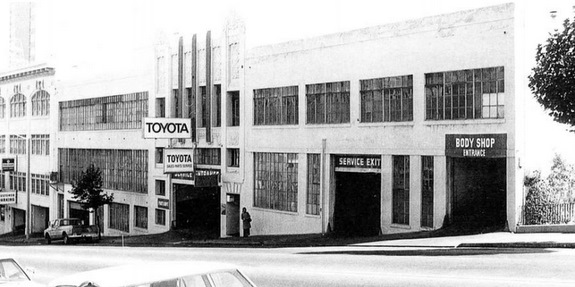

Auto shops began appearing in the city around the time of World War I, growing primarily in the 1920s and largely around a stretch of Van Ness Avenue called Auto Row, according to architectural historian William Kostura [pdf]. Construction of buildings designed for fixing and selling automobiles continued throughout the mid-20th century.

Auto repair prior to the war was largely done as a secondary job in various types of mechanical facilities, and "the first business to advertise in city directories under the heading of 'automobile repair' was, in fact, a bicycle shop" on Larkin Street which began offering the service in 1904, writes Kostura.

But auto shops, if not integrated carefully, can impact a street’s quality as a place to be on foot, on bike, or to pass through on transit, something that city planners have taken more seriously in more recent years.

Transportation planner Jeffrey Tumlin, a principal at Nelson/Nygaard Consulting Associates, thinks there’s a place for auto shops in commercial districts “provided they treat them respectfully.”

“It’s possible to design them in a way that doesn’t destroy the positive qualities of walkable neighborhoods,” said Tumlin.

“For what’s effectively an auto-oriented use, they have some interesting qualities,” he said. “If you can minimize the damage and the danger associated with the driveway, the buildings themselves can be quite lovely. Watching cars being repaired up on their lifts with repairmen wandering around is a kind of interesting urban activity.”

Although Tumlin said they might not be ideal on the city’s “more precious commercial streets, it’s something that can lend authenticity and local character to the more work-a-day centers of neighborhoods.”

“If you recognize that some percentage of San Franciscans will continue to own cars for a long time, that repair needs to happen some place,” he said. “And for people who are getting their cars repaired, when their car’s in the shop, they need to be able to get around without their car, so putting auto repair shops in an industrial ghetto doesn’t really work very well.”

In order to lessen the impacts of auto shops on pedestrians, cyclists, and transit “and make the business a better neighbor,” legislation has been passed to make requirements on auto shops generally more restrictive, explained Radulovich. However, most auto shops were built under the looser regulations of decades ago and “grandfathered” in.

That means a new auto shop built on a neighborhood commercial street like Ninth Avenue today would be subject to stricter requirements, if permitted at all, than it would have been before the 1980s when restrictions on permits were put in place.

Currently, new auto shops are prohibited in residential districts, allowed in industrial districts, and only “conditionally permitted in other neighborhood commercial and mixed-use districts,” said Radulovich. But ”such businesses only have to comply with the current code if they move into another space, or if the building is rebuilt or undergoes certain major renovations.”

For new shops, restrictions are now in place under Planning Code amendments passed in April that were pushed by Livable City and Supervisor Ross Mirkarimi. They require smaller widths for garage entrances, restrict them from being placed “on important walking, cycling, and transit streets across the city,” and require that they be located on smaller side streets where possible, said Radulovich. Car storage is also required to be “screened behind active commercial or residential uses,” he said.

But constructing new auto shops in San Francisco hasn’t been an issue of late, as the demand seems to be dropping. Joshua Switzky of the SF Planning Department said he couldn’t think of any proposals for new repair shops or gas stations in recent years. If anything, he said demand is so low that on some corridors like Valencia Street, “they tend to be the few development sites that are left.”

Last month, the Planning Commission approved a project to redevelop a closed gas station into an 18-unit residential and commercial building on the corner of Valencia and 20th Streets.

Tumlin noted that auto shops can be converted into other uses, granted they’re designed well, and often have useful features like high ceilings, good natural light, and a lack of columns. San Francisco historian and Streetsblog contributor Chris Carlsson said he “would like to turn them all into community centers.”

Some buildings containing auto shops, like those built in the Tenderloin in the 1920s and 30s, have “spectacular” architecture and “bizarrely contribute positively in many ways to the vitality of the commercial districts there,” said Tumlin. Kostura’s report notes that “former auto showrooms, garages, and repair shops have found adaptive reuse as restaurants, stores or offices.”

Still, Radulovich said current rules can make converting auto shops for other uses difficult. “While controls on new automotive repair and service station uses have generally become more restrictive, another provision of the code makes it very onerous to convert a service station to another use,” he said.

And, he noted, increased restrictions on auto shops can face resistance from labor advocates. “Some activists are concerned that they are eliminating blue collar jobs from the city, and limiting peoples’ access to auto repair services in their neighborhood,” said Radulovich.

Indeed, any auto shops that are converted or redeveloped would likely have to be phased out.

“If they choose to move out,” said Shelby, “then maybe we can go towards” turning auto shops into public spaces, residences, other businesses. “But that business is already there, and if they’re still making money and paying their due, then I think it infringes on their rights as business owners.”

This article was revised from its original version on June 6, 2011.