Donald Shoup may be known as a guru of smart parking policy, but even he has found a few surprises in the data collected so far from SFpark.

"The biggest surprise I got was that prices went up and down, but overall, they stayed the same. The average price actually declined by 1 percent," said Shoup, professor of urban planning at UCLA and author of The High Cost of Free Parking, the bible of modern parking policy. "That surprised everybody. People thought it was just a way to jack up prices, but the city specifically said, 'We are going to set prices according to this principle.'"

[Update: The SFpark final report found the average price dropped by 4 percent, not 1.]

SFpark, which uses "smart meters" and ground sensors to measure parking occupancy and adjust prices accordingly, is providing valuable lessons for San Francisco and cities around the world that want to reduce the amount of time drivers spend cruising the streets for a parking space.

The growing body of data collected from the program is shedding more light on the complexities of parking demand. But overall, Shoup says, it's providing hard evidence that raising and lowering meter prices is an effective way to keep enough parking spots available for drivers who need them -- and to help ensure too many spots don't sit empty.

Keeping, say, one parking spot open on every block "will make the transportation work best -- it'll reduce cruising, speed up buses, reduce air pollution," said Shoup. "It's easy to explain [a goal] like that -- we're aiming at what you want to see."

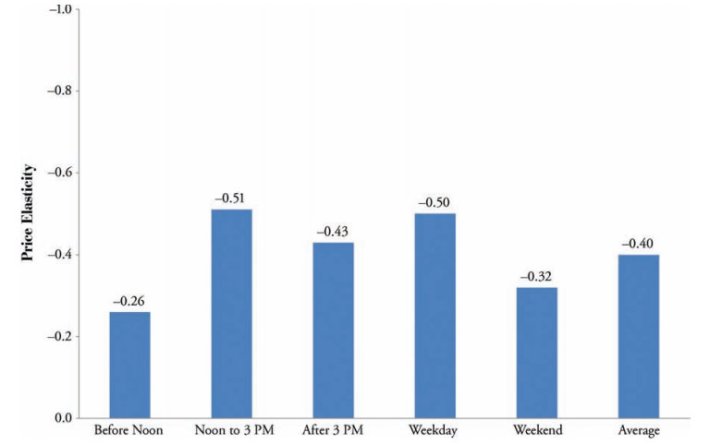

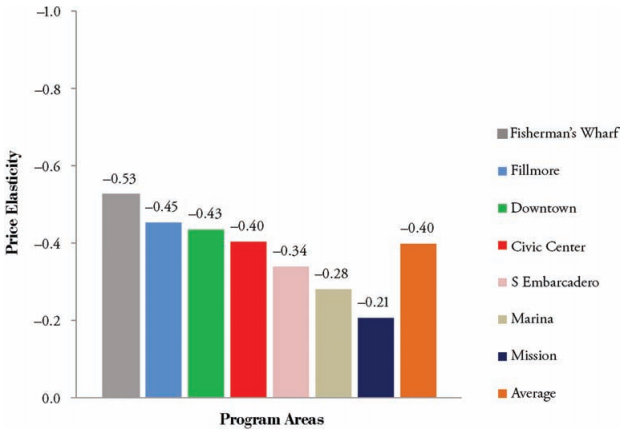

In a recent report [PDF] published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, Shoup and UCLA doctoral student Gregory Pierce explain that since SFpark managers began adjusting meter prices in August of 2011, the "elasticity" of parking demand -- the degree to which price changes affect parking occupancy -- has varied across different locations and times of day (due to different trip purposes, they surmise), and that drivers changed their behavior most profoundly after the second price adjustment, possibly due to a spike in awareness of the program. As prices have been refined, elasticity has declined.

Prices appeared to have the lowest impacts in highly residential neighborhoods like the Mission and the Marina, while retail districts like Fisherman's Wharf and the Fillmore saw the most drastic adjustments to new prices, according to the report.

Parking demand was also affected by temporary events like festivals and construction sites, which Shoup says SFpark should strive to plan for in advance more effectively. SFpark did begin setting special prices at spaces around AT&T Park during Giants games this year. "There are a lot of other things affecting occupancy other than just prices," said Shoup. "It could be road closures, sales in stores, or Christmas season."

As occupancy rates get closer to the target of roughly 85 percent, adjustments to SFpark meter rates have become less drastic and less frequent. Under the last adjustment announced in March, 58 percent of meter rates stayed the same, while 20 percent of meter hours increased by 25 cents, and 22 percent dropped by 25 or 50 cents. In June, the latest adjustment for rates at city-owned parking garages affected only 7 percent of parking hours, and garage rates have generally dropped sharply throughout the course of the program (complemented with signs pointing drivers towards the garages). SFpark managers are allowed to make adjustments every two months at the most.

But a lack of awareness that prices vary between each hour and block can hold back the program's effectiveness, since fewer drivers are looking to park in areas with less demand. For this reason, Shoup and Pierce recommend that SFpark increase the visibility of the program beyond current features like the program's phone app, data-rich website, advertisements, and meter labels. "Many drivers, especially tourists, remain unaware of these price variations and thus miss the opportunity to save money by walking a few blocks from their cars to their destinations," the report says.

The report also calls upon California to tackle the problem of disabled parking placard abuse, pointing to other states like Michigan and Illinois that have removed incentives for drivers to abuse placards to get free parking:

California allows all drivers with disabled placards to park free for an unlimited time at parking meters, so higher prices increase the temptation to abuse placards. Raising prices on crowded blocks may simply drive out paying parkers and make more spaces available for placard abusers. If so, prices will not reduce occupancy, and the price elasticity of demand will remain artificially low.

The SFMTA should also extend its parking meter hours past 6 p.m., when parking demand remains high in many areas, said Shoup. "I hope San Francisco will ask, 'Why is the right price at 7 p.m. on Union Square $0?'" he said. "We have the equipment, all the software, and we just put it to sleep at 6 p.m."

Outdated policies aside, Shoup praised San Francisco for pioneering the most comprehensive system of demand-based parking in the world. "Normally, you expect America to have fallen behind the rest of the world in transportation policy, but this is the one area where the United States has really seized the lead and is way ahead," he said.

Leaders in cities around the world have expressed interest in launching similar programs, Shoup noted, including Rio de Janeiro, which plans to host the Olympics in 2016 but doesn't have a single parking meter on its streets. "They were quite entranced by it," he said.

Shoup calls SFpark a "political success" -- insofar as it's converted existing parking meters (adding new meters is another question) -- and he says the program shows how dynamic parking pricing can be an alternative to congestion pricing that requires less infrastructure and fewer political battles.

"Cities can adopt programs like SFpark even if they do not yet have all the resources and political will to adopt congestion pricing," the report says. "In effect, performance-parking prices are a poor man’s congestion pricing, and they may represent a step toward full congestion pricing."

Down the road, demand-based parking pricing could help make people aware of the hidden costs of car use, say Shoup and Pierce. In fact, they argue, drivers might come to expect the convenience of available parking, even if they have to pay for it. "What seemed unthinkable in the past may become indispensable in the future," they wrote.

"With performance-parking prices, drivers will find places to park their cars just as easily as they find places to buy gasoline. But drivers will also have to think about the price of parking just as they now think about the prices of fuel, tires, insurance, registration, repairs, and cars themselves."