The anger of the protestors who blockaded a Google bus in the Mission on Monday was very real and understandable. San Francisco residents, living in a highly sought-after city with a limited housing supply, are coping with a crisis of skyrocketing rents and evictions. Meanwhile, Muni riders increasingly find their stops blocked by private shuttles that appear to be whisking away the very Peninsula tech workers blamed for driving up rents.

Plenty has been written about the strife caused by SF's housing crisis in the last few years. But as we wrote in February, pointing fingers at tech shuttles doesn't help solve the problem -- if anything, it's a distraction from effective solutions.

The real culprits are the decades-long failures of SF and other Bay Area cities to develop efficient transit systems and the kind of walkable neighborhoods that are in ever higher demand, yet in scarce supply in the region. And deeper than that is the cultural aversion to change and the political establishment that caters to it, avoiding tough but necessary decisions.

Don't get me wrong -- the fact that private shuttles are illegally using Muni stops without paying anything for it is unjust and unsustainable, as Monday's protestors rightly called out. But those specific problems can be addressed by devoting more curb space to transit -- both public and private -- the vast majority of which is currently devoted to free, subsidized personal car storage. The SFMTA's plans to convert car parking to shuttle stops and establish a private shuttle fee system are a step in the right direction.

But what's really hampering Muni performance is all the private car traffic that bogs down buses and the unnecessary frequency of stops. Imagine if protestors devoted this much energy and media savvy to demanding speedy implementation of the Transit Effectiveness Project by City Hall.

Meanwhile, the fact is that the Bay Area can't have the dynamic tech-based economy sought by Mayor Ed Lee and an affordable housing supply for middle-class and low-income people without building substantial amounts of walkable development.

One factor we've pointed out on Streetsblog is that housing development in SF and other cities is hamstrung by minimum parking requirements, meaning housing for people is mandated to come with a certain amount of housing for cars. This adds to the cost of building, owning, and renting that housing, and limits the amount of space for residences or businesses. And as research has shown repeatedly, when housing is bundled with a parking space, residents are more likely to own a car and drive, making the transit system less effective.

Unfortunately, the positions staked out by Supervisors David Campos and Malia Cohen on recent housing development projects coming out of the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan work against the goal of affordability. Campos and Cohen have fought projects on the basis that they don't have enough parking, causing developers to add spaces or subtract apartments, flying in the face of smart zoning policies developed over ten years. Meanwhile, parking-free housing is a growing trend in other American cities.

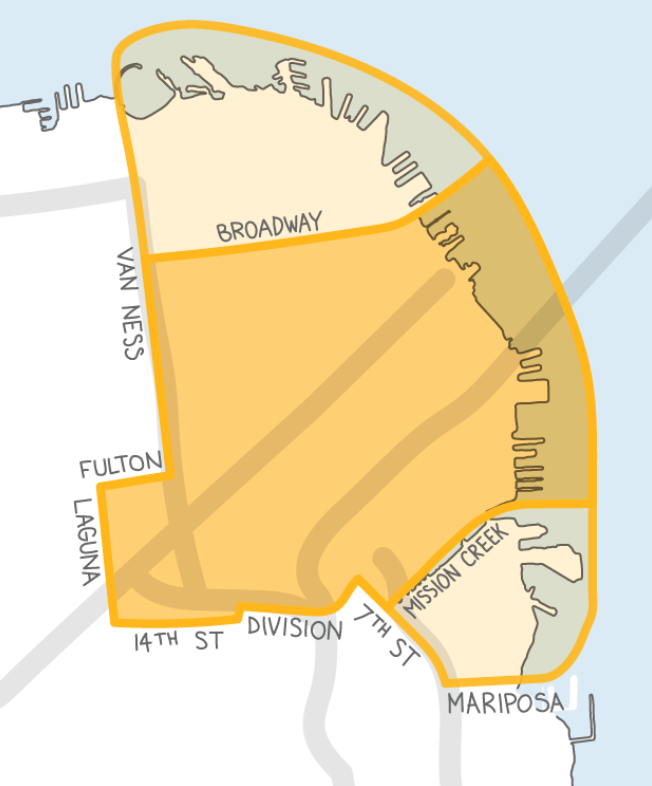

Plan Bay Area is a start on smarter housing development -- it lays out how cities can accommodate population growth around transit hubs like Caltrain and BART stations, minimizing the need to drive and keeping the costs of housing and transportation low.

As David Edmondson of Vibrant Bay Area wrote in November, increased transit-oriented development helped stem the tide of rising rents and displacement in Washington, D.C.:

Rising rents spurred new development, which has halted the rise in most areas and slowed it in particularly high-demand parts of town. Nearly all of this growth has been along the region’s Metrorail subway system, too, so rising population has not equated to rising traffic.

And, importantly for keeping urban character alive, quite a bit of this growth has occurred outside the city core, often in new urban centers in what were suburban strip-mall landscapes. To San Francisco, this has been the equivalent of tens of thousands of new housing units along the East Bay BART lines and Caltrain, and the virtual elimination of the urban strip mall.

That’s not to say DC has been immune to displacement. The once-burned-out H Street NE corridor gentrified quickly, as has Hispanic Columbia Heights. African-American Petworth and Brookland are coming under pressure from well-heeled renters, too.

But the thousands of units in the suburbs and in the city’s center have given these areas time to prepare. Affordable housing, inclusionary zoning, and various direct legislative efforts to keep people in their homes can be attempted, improved, and applied to neighborhoods that have yet to be overwhelmed. Areas without any pressure, armed with these protections, are starting to wonder when their day will come.

In the near term, residents can only do so much to fight the crisis of evictions and insane rents, and it's frustrating. I'm experiencing this myself -- my fiancée and I are fortunate enough to not be at risk of eviction, but we feel trapped in our small studio. Scapegoating private transit that fills the gaps in the public transit system -- perhaps the most visible symbol of change -- is easy, but it's counterproductive.

The bottom line is that San Francisco needs to make the tough political decisions to prioritize people and transit, not cars. Cities up and down the Peninsula and the East Bay need to ditch the suburban model of the 20th century and embrace the creation of more human-scale, transit-friendly neighborhoods that more of us want so badly to live in.