The Belmont City Council is gearing up to decide on a list of infrastructure investments intended to improve safety and reduce traffic congestion on Ralston Avenue. At a community meeting last month, representatives from consulting firms W-Trans and Alta Planning presented their Ralston Avenue Corridor Study, intended "to improve the multi-modal function" of the busy arterial street.

Ralston Avenue is currently dangerous for everyone, with collision rates higher than statewide averages everywhere along the street except west of Alameda de las Pulgas. On average, there are six traffic collisions on or near Ralston every month, nearly all of them injuring at least one person. The most common primary cause is unsafe speed, according to the Belmont Police Department and the StateWide Integrated Traffic Records System (SWITRS).

"This is the predicted result of higher vehicle speeds," said Belmont Planning Commissioner Gladwyn d'Souza. "Both the frequency and severity of collisions rise exponentially with speeds."

Among other things, the draft Ralston Avenue Corridor Plan recommends new sidewalks, curb extensions, high-visibility crosswalks, bike lanes, and even a roundabout. Residents are hopeful the improvements will reduce speeding and allow more people to feel safe walking with their children, but some say the study has ignored its fundamental charge to propose ways to make all modes of transportation function safely along the entire street.

No bike safety improvements whatsoever are proposed for the street's two most challenging sections: from Highway 92 to Alameda de las Pulgas, and from Twin Pines Lane to Highway 101.

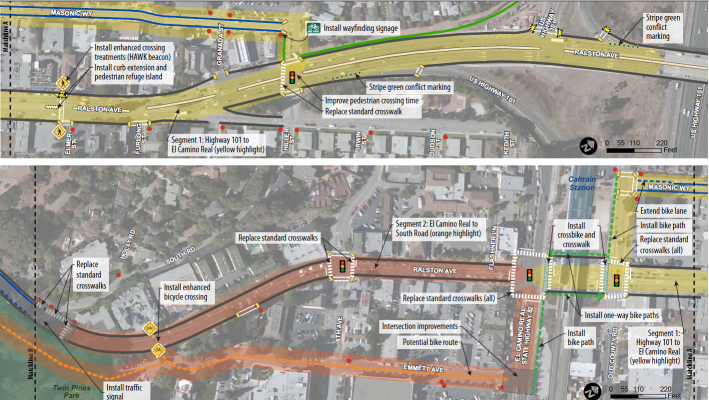

Instead, the consulting team proposes that people riding bikes be detoured through Masonic Way's door-zone bike lanes, the Belmont Caltrain Station (on a series of sidewalks), along El Camino on a future sidepath, across El Camino at a marked but signal-less crosswalk at Emmett Avenue, and through Twin Pines Park on an existing paved path back to Ralston Avenue east of the entrance to Notre Dame de Namur University.

"We've heard from the the community that many folks are already using this route, so we want to provide way-finding signage and sharrows where necessary to direct bicyclists down this route," said Alta Planning Senior Associate Jennifer Donlon Wyant. "We want to promote access to that route that's already being used but that maybe only a few folks know about."

Meanwhile, between Highway 92 and Alameda de las Pulgas, no such alternate route to Ralston even exists, so no bike safety improvements were recommended.

In response, some residents pointed out that cyclists are forced onto alternate routes by dangerous conditions, and that inconvenient, indirect side routes don't encourage people to bike. "These alternative routes that people are taking on bikes are because Ralston is so dangerous for bikers," said resident Ed Mitchell. "If we figure out a solution to that, there will be a dramatic increase in bikers and decrease in traffic."

"Redirecting bicyclists to a less crowded street should only be done if the less crowded street is also shorter, faster, and more direct," wrote Steve Vanderlip, founder of Bike San Mateo County. "People will not use these maybe safer but longer and less convenient routes. The time factor is important."

The Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition (SVBC) agreed, and called for continuous bike lanes on all of Ralston Avenue west of Highway 101, acknowledging that this would require removing vehicle parking and travel lanes in places.

W-Trans said that adding bike lanes on Ralston west of Alameda de las Pulgas would require reducing the number of traffic lanes from four to two. Many such "road diets" have been implemented in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties, including Palo Alto's Arastradero Road, a busy arterial street that carries up to 20,500 vehicles per day, as well as hundreds of children walking and biking to school and many adults commuting by bike as well. Upper Ralston carries up to 25,000 vehicles per day but under the current conditions, very few people walk or bike there.

Belmont Planning Commissioner Gladwyn d'Souza explained how reducing the number of travel lanes would eliminate the street's main hazard -- speed. "The number one complaint over the last 25 years in the corridor is speeding and the lack of enforcement. A road diet addresses the problem by building lower speeds and enforcement into the street."

But W-Trans said that according to the computer models they use to predict future traffic volumes, a road diet on upper Ralston would create four- to six-minute delays for drivers -- in 2035. These models assume a continual 1 percent annual growth rate in traffic volumes and also assume that no one would shift any trips from driving to walking or biking even if wider sidewalks and buffered bike lanes were built.

On the busiest section of Ralston Avenue between El Camino Real and Highway 101, which carries up to 38,000 vehicles per day, wide, buffered bike lanes on both sides of the street could be created by removing parallel car parking. W-Trans doesn't recommend this. "We heard from business owners who were adamant that they didn't want to lose that on-street parking along the front of their buildings," W-Trans Principal Planner Mark Spencer explained.

In response, SVBC wrote a letter citing research conducted in San Francisco, Portland, Long Beach, Toronto, and New York City showing that "an increase in bicycle facilities has positive benefits for businesses," mainly increased retail sales for stores located on streets where bike lanes had replaced parking.

The set of pedestrian improvements included in the study are more comprehensive, and would create a continuous sidewalk along the entire length of Ralston Avenue. Dozens of high-visibility "zebra-type" crosswalks would be installed at intersections all along the street, along with some sidewalk curb extensions and new sidewalks where none exist today.

But some existing hazardous conditions would remain, including long distances and wait times to walk across both Ralston Avenue and El Camino Real in downtown Belmont, narrow sidewalks downtown, and missing crosswalks needed to get across Highway 101 on foot. One critical improvement that residents have been demanding for years isn't being recommended either -- a safe pedestrian crossing of Ralston Avenue between 6th Avenue and El Camino Real -- where San Mateo resident Lourdes Gallegos was struck and killed by a car driver in December 2011.

The Ralston Avenue Corridor Study will be presented to the Belmont City Council for review later this Spring.