San Francisco is quickly adding residents, but very few cars.

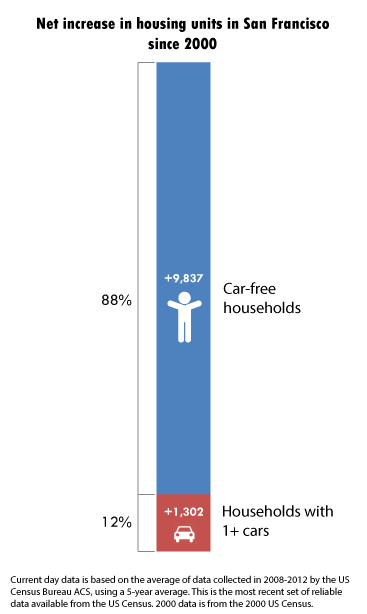

Between 2000 and 2012, the city has seen a net increase of 11,139 households, and 88 percent of them have been car-free. That's according to an analysis of U.S. Census data by Michael Rhodes, a transportation planner at NelsonNygaard and a former Streetsblog reporter. One net result of this shift is that the proportion of San Francisco households who own zero cars increased from 28.6 percent in 2000 to 31.4 percent in 2012, the fifth-highest rate among large American cities.

The stats show that the city's average car ownership rate is declining, even as the population is growing. The data don't distinguish where specific households are foregoing cars, so this doesn't necessarily mean that the residents of all the new condo buildings going up are car-free. But the broader effect is reverberating throughout the city, whether car-free residents are moving in where car-owning residents previously lived, or residents are selling their cars.

This finding flies in the face of complaints from NIMBYs who protest new housing developments that forego parking, based on a faulty assumption that new residents will own cars anyway and take up precious, free street parking. That's one of the arguments heard from proponents of the cars-first Proposition L, who complain that "the City has eliminated the time-honored practice of creating one parking space for every new unit."

"A lot of people who are moving here are choosing it because it's a place you can get around without a car," said Livable City Executive Director Tom Radulovich. "People will self-select. If convenience for an automobile is their criterion, there's a lot of places in the city and elsewhere" to live.

Radulovich noted a number of changes in the 21st century that have made it easier not to own a car. San Francisco has expanded its bike lanes, car-share services now exist, and taxi service has improved (besides the new "ride-share" apps like Uber and Lyft). Muni, BART, and Caltrain ridership have also increased to record levels over the years.

And, Radulovich noted, even the new wave of tech workers tends to get to work on shuttles -- unlike those in the dot-com boom of the 90s, who favored living near highways 101 and 280 so they could easily drive to Silicon Valley.

"There's a lot of people who get to work on the tech buses -- those might've been car owners a decade ago," he said.

Across the country, Americans are driving less, and millennials in particular are generally more interested than earlier generations in car-free city living. Radulovich pointed out that it's often older residents who insist that the city build more free parking (see: Prop L). "There's definitely a set of cultural expectations, from those raised in the '50s and '60s, for car ownership and automobility," he said.

According to the Census' American Community Survey, 31.4 percent of SF households surveyed in 2012 were car-free. That's up from 29.8 percent in 2009 and 28.6 in 2000. (Note: The 2013 SFMTA Transportation Fact Sheet incorrectly cited the most recent stat as 21 percent.)

Even among the 12 percent of new households since 2000 that do own cars, many are car-lite -- not each individual owns a car. SF has actually seen a net decline in two-car households despite growth in total households, while the number of households with three or more cars increased by slightly more.

Here's a more detailed breakdown of changes in car ownership rates since 2000, provided by Rhodes:

| Unit type | Change |

| All units | +11,139 |

| Car-free | +9,837 |

| 1 car | +1,242 |

| 2 car | -1,123 |

| 3 or more cars | +1,183 |

The statistics show the efficacy of providing better alternatives to car ownership, but they also underscore the importance of building more housing in walkable, transit-oriented neighborhoods throughout the Bay Area.

"Certainly, we need to find places in those [walkable San Francisco] neighborhoods where we can build. The good news is, if the new households that are coming to those neighborhoods are car-free, then we can spend a lot less space on parking and use that for housing, and the automobile-oriented impacts [like traffic] of increased density may not materialize," said Radulovich. "But San Francisco's a small place -- and if we've got a whole generation that wants walkable, urban places, and this is the only place in the Bay Area that offers that, then there's gonna be a lot of competition for it."