BART's board and staff is working on a $3 billion bond that, if approved by the BART Board this summer, will appear on the November ballot. If the voters go for it, it will help fund upgrades and maintenance to existing infrastructure. Even though it's primarily about maintenance and upgrades to existing tracks and tunnels, advocates are pushing to have $200 million of it earmarked towards more planning for a second Transbay crossing.

Either way, number one on the to-do list is replacing BART's forty year old signaling system, explained Alicia Trost, a BART spokeswoman. "It's the number one cause of delays," she said. Right now, BART uses a fixed-block signal system, she explained--which means trains are kept from crashing into each other by making sure two trains never enter the same fixed length of tracks. Riders experience the downside of this old system when their trains stop in the Transbay tube for no apparent reason; the train is waiting until the train in front, which may actually be a safe distance away, has left the next segment of track.

Under the new train system, computers simply maintain a minimum distance between trains as they move, which will let "the new train cars run more frequently. Headways would be improved," she said. There are also portions of the Market Street tunnel that are leaking water and need to be sealed. In addition, she said, 90 miles of rails would be replaced along with electrical power systems.

All necessary work, but this falls short of what advocates want to see. "We have a responsibility to plan for the future of the system," said Ratna Amin, Transportation Policy Director for the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR). And while she agrees there are immediate and pressing upgrades and repairs required for existing infrastructure, that shouldn't supplant future planning. "You don't abandon one and work on the other," she said.

No argument there, but BART's Board of Directors is already concerned about asking for too much with the bond, considering that it would cost some $13 billion to fund a second set of Transbay tubes. A poll done earlier this year shows that if they up the amount on the bond beyond about $4.5 billion, it starts to fail to reach the two-thirds voter threshold to pass. The bond will be paid back by a property tax that will come to roughly $45 a year per property owner, for the next three decades.

Additionally, the research shows that while people support the idea of a second set of tubes, they don't give it a high priority. But there is something the BART board of directors can do to start the ball rolling. And this is what SPUR is advocating for with a white paper it released a few days ago.

"The staff proposal has a $200 million pot for long term planning--but there's no commitment in there" to plan for a second set of tubes, said Amin. "It could be zero. It could be $200 million." Advocates want that money committed to studying the tubes. And if a comprehensive study is done, the money will eventually come from Washington, they hope.

That said, this is hardly the first time advocates and BART officials themselves have argued for a second set of BART tubes. Nevertheless, "I think money from the bond can help make it more shovel ready, so when a new congress comes along that values big infra projects this will be ready to go," said Jonathan Fearn, an advocate with “Connect Oakland," a group that wants to remove I-980 from where it divides downtown Oakland and replace it with a surface level street, and a BART and Caltrain tube underneath.

"The Bay Area is an economic engine nationally. The federal government has to come in and help make the economy more resilient," he said.

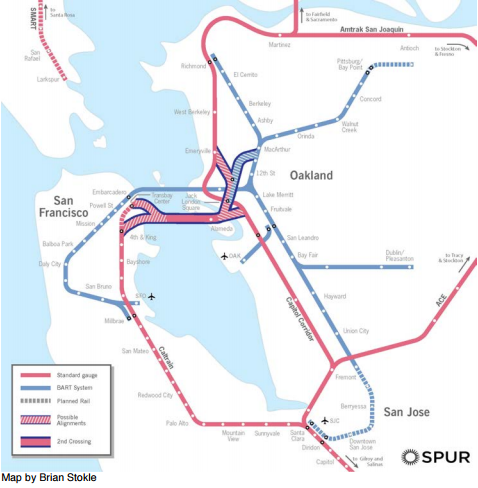

SPUR's white paper, meanwhile, envisions several options, including one that wouldn't carry BART's current fleet of trains.

"We have to separate BART the technology from BART the system," said Amin. Because BART is non-standard gauge, there may be a greater advantage, she explained, to building tubes that would connect up Amtrak's Capitol Corridor, High Speed Rail and Caltrain across the Bay.

Electrification would allow speeds and train frequencies that would rival and exceed BART's current fleet. Fearn, however, thinks if they are going to go through the expense of building a second crossing, it should have four tubes--two for BART and two for standard trains.

"If you're making an investment that large, make it as accommodating as possible," he said. "We saw how short-sighted we were with two tunnels when we built the original crossing; we don't want to be that short sighted moving forward."

Regardless, Amin and Fearn agree that the Bay Area economy is endangered by having only the one crossing. "It's a risk to have no redundancy," said Amin. "We have to keep planning it today. We don't have to built it tomorrow. But we have to build consensus."