How can we make it easier to get around between San Francisco and San Jose? That was the topic discussed by a group of transit advocates and professionals last Wednesday in Palo Alto at a Caltrain / 101 Corridor Vision Forum. The corridor is today plagued by crowded trains, a congested Highway 101, and ineffective public bus services.

“There's an opportunity for Caltrain to leapfrog and innovate beyond most of the rail systems in the United States,” said San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) Transportation Policy Director Ratna Amin. "Let's imagine a railroad that has so much capacity and utility that people are using it for all kinds of trips."

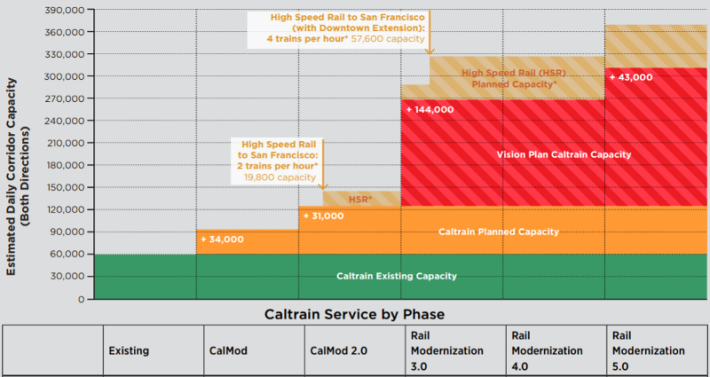

SPUR published a report [PDF] in February that laid out how Caltrain could triple peak-hour capacity over the next decade if major investments are made. The most aggressive scenario would run up to twelve eight-car trains per hour by constructing a separate set of tracks for California High Speed Rail and rebuilding at least seven stations, for a total cost of up to $20 billion. Less ambitious options could still double peak-hour capacity within the confines of the planned blended system in which the two rail systems will share tracks.

These scenarios are further reaching than those envisioned by Caltrain itself, which is only beginning to plan for service improvements beyond electrification in 2021. The electric trains the agency is purchasing will allow for level boarding on the platforms shared with High Speed Rail by including two sets of doors per car, one high and one low. Level boarding at all stations will require them to rebuild platforms at the higher level.

Caltrain’s success also depends partly on other transit systems being more extensively utilized, including the region’s highways. Lacking even a carpool lane through San Francisco and San Mateo counties, Highway 101 penalizes those travelling the most efficiently.

"Highways are an untapped resource for transit," said TransForm Senior Community Planner Chris Lepe. "On Highway 101, three percent of vehicles - carpools with at least three people, shuttles, and buses - carry 20 percent of the people. Solo drivers make up 75 percent of the vehicles and carry about half of the people."

Caltrans and transportation officials in San Mateo County favor widening Highway 101 to ten lanes there to create new express lanes, which are free for carpools and buses but admit solo drivers for a fee that is set at a price that maintains them in a congestion-free condition. Transit advocacy groups are lobbying for existing travel lanes to be converted to express lanes instead, which will save an estimated $200 million that could be invested in better transit services.

“Caltrans is about to make this major investment that depends on high-occupancy vehicles, but doesn’t know how to promote the use of high-occupancy vehicles,” commented Friends of Caltrain Director Adina Levin.

There’s certainly no shortage of local expertise on ways to reduce demand for driving, with many of the region’s major employers getting nearly half of their commuters to work without driving alone using various incentives including free public transit passes and free shuttle vans and buses.

Stanford University, subject to a fixed cap on vehicle trips in and out of its main campus near Palo Alto since 2000, has achieved the most impressive results, with 19 percent of employees using Caltrain, 11 percent bicycling, nine percent in carpools, and another 11 percent walking or riding buses. The university funds its transportation programs by charging to park motor vehicles on campus on weekdays. Employees receive free train and bus passes if they decide to forgo purchasing a parking permit.

“We are one of the few large employers in Silicon Valley that charges for parking,” said Stanford University Senior Transportation Planner Carolyn Helmke.

But using parking revenues to pay for transit passes is still rare in the region. Palo Alto’s City Council approved a budget on Tuesday that will do exactly that, using $480,000 in revenues from newly increased public garage parking pass prices to fund its downtown Transportation Management Association.

The Caltrain / Highway 101 Vision Plan Forum will repeat on July 19 at 6:30 pm at Redwood City City Hall, 1017 Middlefield Road, with the same speakers representing SPUR, TransForm, Friends of Caltrain, and Stanford University.