Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Over the holidays, California Transportation Commission staff released its recommendations for Active Transportation Program grants in the Statewide competition and the Small Urban and Rural competition. These two parts make up sixty percent of the total ATP Cycle 4 funding; the remainder will go to projects chosen by large regional Metropolitan Planning Organizations in the spring.

Notably in this fourth cycle of the program, there was more money available than in past rounds, in part because of the passage of S.B. 1 and the failure of Prop 6. But staff recommended larger projects than have applied in past rounds, so fewer total projects were chosen.

As has been true since the ATP was formed, competition was fierce, as many more projects applied for funding than was available. Staff chose 55 projects for a total of $262.5 million over the next four years, but received more than 550 applications. In the past, projects that scored 88 out of 100 points were able to secure grants, but this time around--at least in the statewide competition--the cutoff was at 90 points, and even then not every project scoring that high was successful.

This is in part because, according to Laurie Waters, the ATP program manager at the California Transportation Commission, both projects and applications have been improving over time. But it is also because at public workshops on the ATP there was a push to fund larger, more transformational projects that could produce a greater mode shift towards active transportation, she said. The application process was adjusted to separate projects into category by size, and by infrastructure vs non-infrastructure, to encourage a wider variety of projects to apply as well as to keep from discouraging smaller projects from competing.

But larger projects cost more money, so they suck up the funding at a faster rate, making the competition tougher for everyone anyway.

Over forty applicants requested $10 million or more, and sixteen requested over $20 million. According Waters, past funding rounds have seen maybe one such large application at the most. The average request during the last cycle, she estimated, was around $2 million, and this time it averaged $4 million.

Staff recommended 45 projects, for a total of $219 million, in the Statewide competition, and ten projects, for $44 million, in the Small Urban and Rural component. For comparison, the Cycle 2 funding, awarded in 2015, had about half the funding but gave it to 86 projects.

Waters said staff had expected that the increase in funding for this round would lead to being able to fund good projects that came in with lower scores, but found that the opposite happened.

The ATP has what may be the most complex and rigorous scoring system of any transportation funding program in California, and new layers were added this round because of the separate competition categories. The guidelines lay out specifically what the program is looking for. Teams of two work score applications against a rubric—there were five separate ones this round—and staff conducted trainings and created a check system to make sure that scores were consistent. Scorers do not work on applications they may have an interest in.

Several areas of the state were quite successful in this round, including Los Angeles, Kern, and Santa Barbara counties. Large projects in Humboldt, L.A. County, Compton, Long Beach, and Placer County were recommended for funding. In the small urban and rural component, Monterey, Chico, and Goleta will all see funding for relatively large infrastructure projects as well.

However, only one project in the Bay Area—safety improvements at the Alemany interchange in San Francisco—was recommended, despite many applications submitted in the nine-county area. The reasons are not entirely clear. They could reflect the relatively high level of biking and walking infrastructure that already exists in many Bay Area cities, making it harder for them to show need than areas that have no infrastructure to begin with.

Waters says CTC staff remains committed to working with less successful applications to make sure their projects don't fall by the wayside."My greatest worry," said Waters, "is that agencies who struggle with the ATP application process may give up.”

That is probably not an issue in the Bay Area. Its regional planning agency will submit its own list of projects in the spring, and that will likely contain at least some of the higher-scoring but unsuccessful projects from the statewide competition. Nevertheless, it is discouraging for applicants who worked hard—the ATP application process is complex and time-consuming—and scored high but didn't make the cutoff. There are a lot of projects that scored higher than 80 points.

The Cycle 4 funding will be allocated over a period of four years, beginning in 2019 through 2023, so even the projects that have been recommended will not be built right away.

And that's a problem. The mode shift promised by increased investment in infrastructure and programming to encourage active transportation needs to happen quickly. The California Transportation Commission points to the ATP as an example of the state's commitment to meet its greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, but at the same time they are allocating much more money to projects that encourage and enable single occupancy vehicle use.

These staff recommendations will be discussed and voted on by the California Transportation Commission at its January meeting in Rocklin. Also on the agenda for that meeting is a discussion of Caltrans' analysis of ATP achievements so far.

The metropolitan planning organizations' recommendations for projects in their areas are due to the CTC by April 30, and the plan is to vote on them in June.

Statewide Component: $219m for 45 projects

In the statewide component, every winning project scored at least 90 out of 100 points on project criteria, and the limited funding meant that two projects that scored high enough came up short. Walk Isabella in Kern County was recommended for only $2.7 million of the $6 million it requested, and improvements around Alexandria Avenue Elementary school in Los Angeles received nothing.

Among the statewide projects recommended for funding were five plans:

- Parlier Bicycle and Trails Master Plan

- City of Mendota Safe Routes to School Master Plan

- City of Gustine Active Transportation Plan

- LA DOT Safe Routes for Seniors

- Pedestrian plans for disadvantaged communities in unincorporated Los Angeles County

There were also two non-infrastructure programs, both versions of Safe Routes to Schools programs: one in Butte County—incorporating a resource center and several community projects—and another in Monterey County.

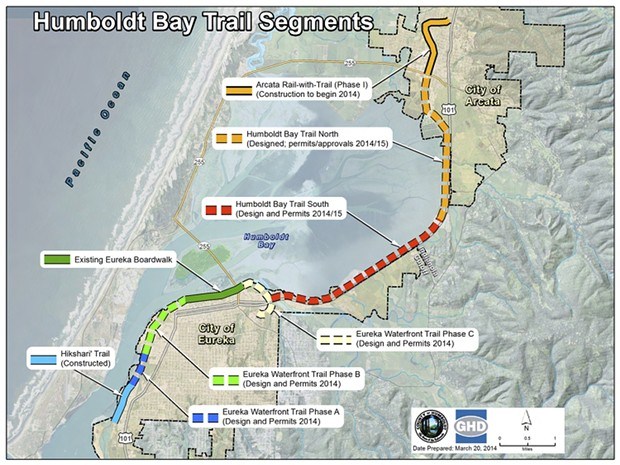

The rest of the projects are all infrastructure, ranging from bikeways and trail connections to sidewalk improvements to improved pedestrian crossings. The largest projects are the completion of a major path between Eureka and Arcata in Humboldt County, safety improvements around Liechty Middle and Elementary Schools in Los Angeles, and Blue Line station improvements in Artesia and Compton.

The Central Valley—Fresno, Kern, Butte, Merced, Stanislaus, San Joaquin counties—as well as southern California regions—Riverside, LA, San Diego—did well. See the complete list of recommended projects here.

Small Urban and Rural: $44 million for ten projects

Most of these are smaller projects, and many combine infrastructure and programming—for example, UC Santa Cruz is recommended for a bike path improvement combined with a safety education program. The largest projects in this group are the Fort Ord Regional Trail and Greenway in Monterey and the 20th Street pedestrian/bicycle overcrossing in Chico.

The projects recommended under the small urban and rural component have received slightly lower scores overall—which was one of the reasons for creating a separate competition for these areas, since they have a harder time competing for funding against areas with more planning capacity. Nevertheless, they all scored 85 points or more. See the complete list here.