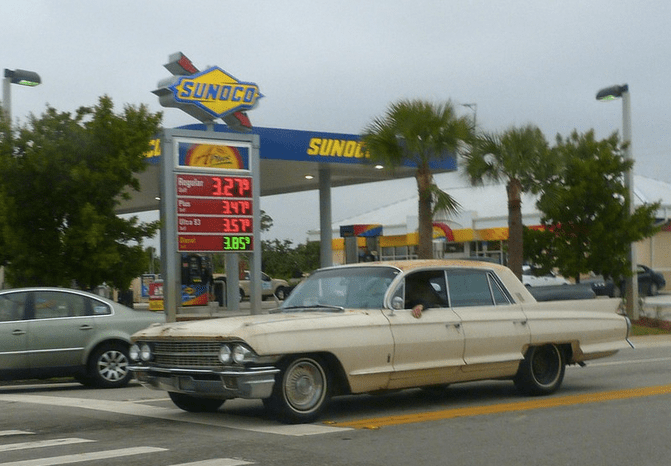

The federal government just finalized its weakening of fuel efficiency standards, despite knowing that they will be sued by states and environmental organizations. The weaker standards call for an increase in fuel efficiency of 1.5 percent per year, instead of the more stringent standards established under the Obama administration of five percent every year. Automakers–some automakers–complained that they would not be able to meet those standards, but evidence from past regulations shows this is not true.

That is, they made the same complaints about the original Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards. But it turns out that not only did they meet the standards handily, automakers also spent time and money developing faster and more powerful engines at the same time. In other words, if those first, hard-fought standards had been more stringent, vehicles could have become more efficient faster.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in the last few weeks, it’s how much an effect driving overall has on air quality. And it means we know what to do about it: drive less. If courts allow the new federal rules to stand, that may be the only way we can clear up air quality and reduce climate emissions.

The new rules also play havoc with ongoing regional air quality and transportation plans. Those plans rely on the previous standards being in place to meet federal air quality rules. With weaker standards, regions will have a harder time meeting air quality standards, and their plans will not be certified, which will jeopardize funding for all the transportation projects in them.

If automakers are not forced by regulators to increase the fuel economy of cars–which incidentally also decreases emissions–they won’t do it, as evidenced by the results of the CAFE standards. They’ll put their research and development money elsewhere.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration made a lot of arguments about why the standards should be less strict than the ones established under the Obama administration, but none of them are strong. For example, they claimed that new cars will become more affordable, and therefore people will replace old gas guzzlers–but they will also be paying more for fuel. That works out well for somebody.

Between plummeting gas prices and slow sales of electric vehicles even before the bottom dropped out of the economy, these rollbacks will lead to less efficient vehicles over time, as well as more emissions.

As Emily Mangan points out at Transportation for America, the last few weeks “ha[ve] also shown us the deep value of having other transportation options, especially for those who need it the most.”

Over 600,000 transit commuters work at hospitals, in doctor’s offices, or as home health providers; 165,000 people take transit to jobs in grocery stores or pharmacies; and 150,000 workers in social services commute on transit. Transit is essential now more than ever, and it will be essential to getting our economy back up and running again.

It’s time to sit back and think what kind of world we want to live in when we start recovering from this pandemic. It’s probably not one filled with inefficient, polluting cars that could be better, if standards were stronger.