One of the nation’s largest e-scooter operators is in hot water for violating labor regulations in San Francisco — and it’s sparking a dialogue about what the micromobility gig economy means for the mobility futures of cities far beyond the Bay.

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency recently announced that as of July 1, it would suspend the permit of one of the longest-standing micromobility companies operating on its streets, Scoot, which was acquired by scooter giant Bird in 2019.

To dissuade scooter-share outfits from over-relying on gig-economy workers to maintain, charge, and rebalance their fleets — a controversial business model that some advocates argue leaves workers vulnerable, and has a track record of poor compliance with city regulations about redistributing fleets in low-income and BIPOC neighborhoods — the SFMTA has required scooter companies to use primarily in-house employees, and to secure approval from the agency if they do use subcontractor labor.

That was bad news for Bird-owned Scoot, whose parent company is increasingly reliant on its controversial “Fleet Manager” program to keep scooters rolling. Marketed as a franchise-like option for enterprising micromobility professionals, a small number of of Fleet Managers are often responsible for almost every aspect of maintaining Bird-owned scooters — but not such a small number that Bird didn’t somehow manage to fail to register three of those subcontractors.

Bird says the whole situation is a “procedural mishap that occurred while urgently providing existing local businesses an alternative source of revenue during the pandemic,” and expects to have its permit reinstated soon. But some of its competitors say the ousting is just the avian operator’s latest failure to comply with city regulations — and that the Fleet Manager program is not delivering on cities’ mobility goals.

“[Bird’s Fleet Manager program] essentially amounts to a complete outsourcing of Bird’s operations to franchisees, who assume full responsibility for managing, maintaining and operating Bird’s service on the ground,” said Russell Murphy, a spokesperson for Lime, a rival outfit. “We’ve seen in other cities how this results in substandard service for city residents, and how it often violates city regulations, including around deploying in lower-income communities, as the fleet managers are disincentivized from meeting these requirements.”

But whether any other scooter company’s labor model is better poised to deliver on cities’ future mobility goals is still the subject of advocate debate — and it could have huge implications as micromobility becomes a bigger part of the U.S. transportation landscape.

Fleet mismanagement?

Created in 2018, Bird’s Fleet Manager program has long been marketed as a promising alternative for micromobility entrepreneurs seeking a greater sense of ownership in their work with the company — not to mention a larger share of the profits from rides in their area than they might get from picking up the odd scooter to charge on the street.

But that sense of ownership is only a sense. Under the model, Bird essentially leases a small fleet of scooters to the Manager — 100 is typical — in exchange for an undisclosed equipment fee that the manager must pay back as “her” vehicles draw fares over the course of the partnership. After the debt is paid, managers then earn up to two-thirds of the revenue generated by the scooters, less a small security deposit on each scooter, which Bird keeps.

Reports are mixed on whether that deal is a good one for the contractors. Some successful Fleet Managers say they make as much as $5,000 a week — particularly those who operate successful bike shops and logistics companies either in addition to or prior to their work with Bird — and Bird says the program now has a median take-home pay of $70,000 a year after fees are paid back. Others claim the program earns them far less while functionally requiring constant uncompensated overtime to meet Bird’s rigorous performance metrics that demand that scooters get charged and put back on the street as fast as possible. One manager told One Zero that he ended up roughly $40,000 in debt once the costs of a cargo van, warehouse rental, and repair costs were factored in, and ended up spending some nights “camping in his van on the street to study the public’s scooter habits” to avoid having some of his vehicles taken away by the company due to underperformance.

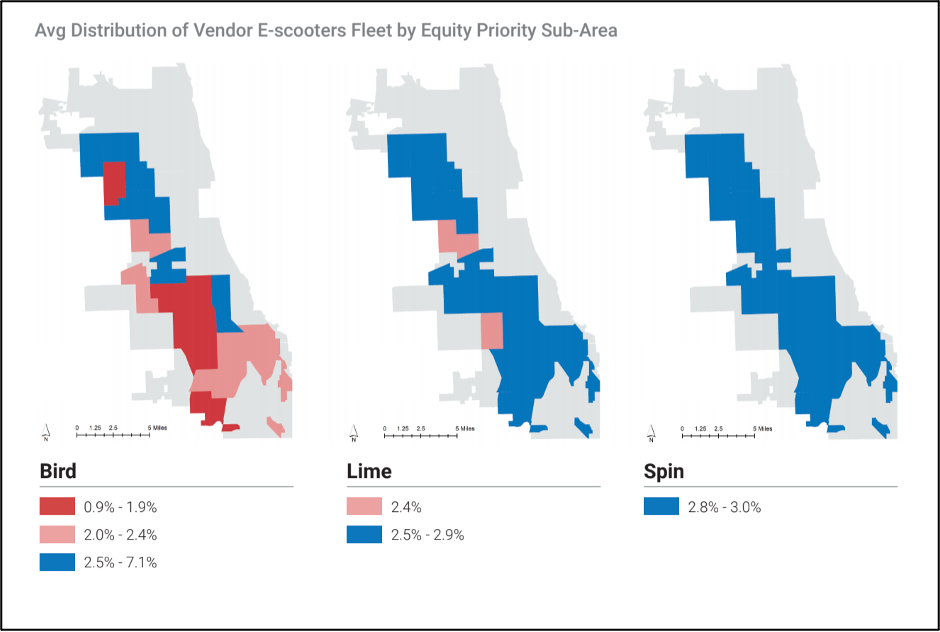

Some advocates say the terms of the Fleet Manager program — not to mention the looming debt — are a recipe for contractors to put their personal profit over the mobility goals of the cities with which scooter companies partner. In May, Bird was cited nearly 250 times by the city of Chicago for struggling to meet city requirements to redeploy at least 50 percent of scooters in underserved neighborhoods called “equity priority sub-areas,” despite the fact that the company’s algorithms are optimized to comply with those rules. (Competitors Lime and Spin had eight and one citation, respectively.)

Bird did eventually bring its managers into compliance, but faced similar citations in Minneapolis soon after. And some advocates say it’s not surprising that often-indebted workers put their own earning potential over local mobility justice goals — just like app taxi drivers have long been legally permitted to do in some communities. (Bird was founded by Uber and Lyft veteran Travis VanderZanden, who remains CEO.)

“Smart fleet managers, just like smart drivers, are going to react to the way the incentives are built,” said Colin Murphy, research and consulting director for the Shared Use Mobility Center. “Unless you’re amping up the incentives to get the vehicles to the equity priority areas, those areas are going to get shortchanged. Contractors are not in the business to maximize the mobility of cities; they’re there to make a living.”

The right labor model

But despite criticism of the Fleet Manager program, advocates are divided on whether other micromobility labor models are all that much better — and whether the industry can equitably upend car dependence without building that revolution on the backs of gig economy workers.

Today, most dockless scooter and bikeshare vehicles are kept charged by a mix of ad-hoc side hustlers with a variety of cutesy names (e.g. Lime Juicers) — and a less visible universe of subcontractors who repair and redeploy the fleet, with additional in-house hiring in markets where cities discourage the excessive use of contractors, like SF. Bird argues that its Fleet Manager program actually isn’t substantially different than what its competitors do, but its model at least enables a few enterprising individuals to score a good annual wage, rather than endlessly hunting for a vehicle to charge for as little as $3 to $5 in cities like Minneapolis, or taking on a relatively low-paying operations contract. Glassdoor estimates that mechanics and operations specialists working as contractors for Lime in the midwest earn between $13 and $18 an hour, which maths out to less than half of a fleet manager’s median wage.

But while defenders of gig economy labor counter that flexibility is simply worth more to contractors than consistently high wages, some advocates have wondered whether the nature of contract work itself is incompatible with a strong micromobility program that complements cities’ long-term transportation objectives — like loosening car dominance.

“The best thing would be to have actual employees doing this work instead of having this atomized system of actors competing with one another,” said Murphy. “That’s really how you align a city’s goals with an operator’s goals.”

That’s part of why micromobility company Spin made the decision in 2019 to ditch the contractor model almost completely. With rare exceptions when the company is ramping up operations quickly — the company worked with a small number of contractors on Chicago’s 2020 scooter pilot, which required it to rapidly deploy more than 3,300 scooters onto Windy City roads in just three months — Spin oversees nearly all of its operations employees in-house. Reps have credited the model with their success in keeping scooters running during the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown when other companies pulled back, and that it’s critical to maintaining strong partnerships with cities looking to reduce private vehicle reliance.

“Compliance is not the sexiest thing in the industry, but it’s what we care about most,” said Maria Buczkowski, a spokesperson for the brand. “If we’re going to go into an agreement with a community, we’re gonna try our best to follow the rules and help them meet their goals.”

But Spin’s success has an asterisk that might turn off some sustainability advocates: its owned by automaker and mobility conglomerate Ford. And that means that unlike start-up Bird, which is expected to go public any day now, it has less of an incentive to ruthlessly cut labor costs to attract venture capital dollars — exactly what it claims the Fleet Manager Program does in its most recent investor deck.

“It definitely helps not to have to think about new funding rounds and what VCs want all the time,” added Buczkowski. “I would be naïve if I said we don’t benefit from being owned by a company that really values its employees.”

Of course, few sustainability advocates would propose that the road to ending car dominance runs through Detroit, and that Spin’s real market advantage is its willingness to act essentially as a vendor-operator for city agencies rather than a private mobility outfit in its own right. The company recently won a contract with the city of Pittsburgh to operate one of the first mobility-as-a-service apps in the U.S., and will even provide discounts to riders who use its scooters to connect to transit.

Seen through that lens, some advocates are wondering whether all he labor reform in the world might not mean much until cities start reckoning with car dominance in more fundamental ways — and then demand that their private partners adopt workforce policies that match those goals.

“I think the most important thing is just that cities have very clear [mobility] goals, rather just saying, ‘Hey free market, come and solve our 50-year-old problems without how we design a city,'” said Murphy. “We’re looking too much for this new class of devices to upend these much larger systemic issues. That’s not realistic.”