The collapse of a bridge in Pittsburgh is just a preview of potential disasters to come under the new infrastructure legislation, which continues to allow states to prioritize building new capacity for drivers over fixing the dangerously broken infrastructure they've already got, advocates said.

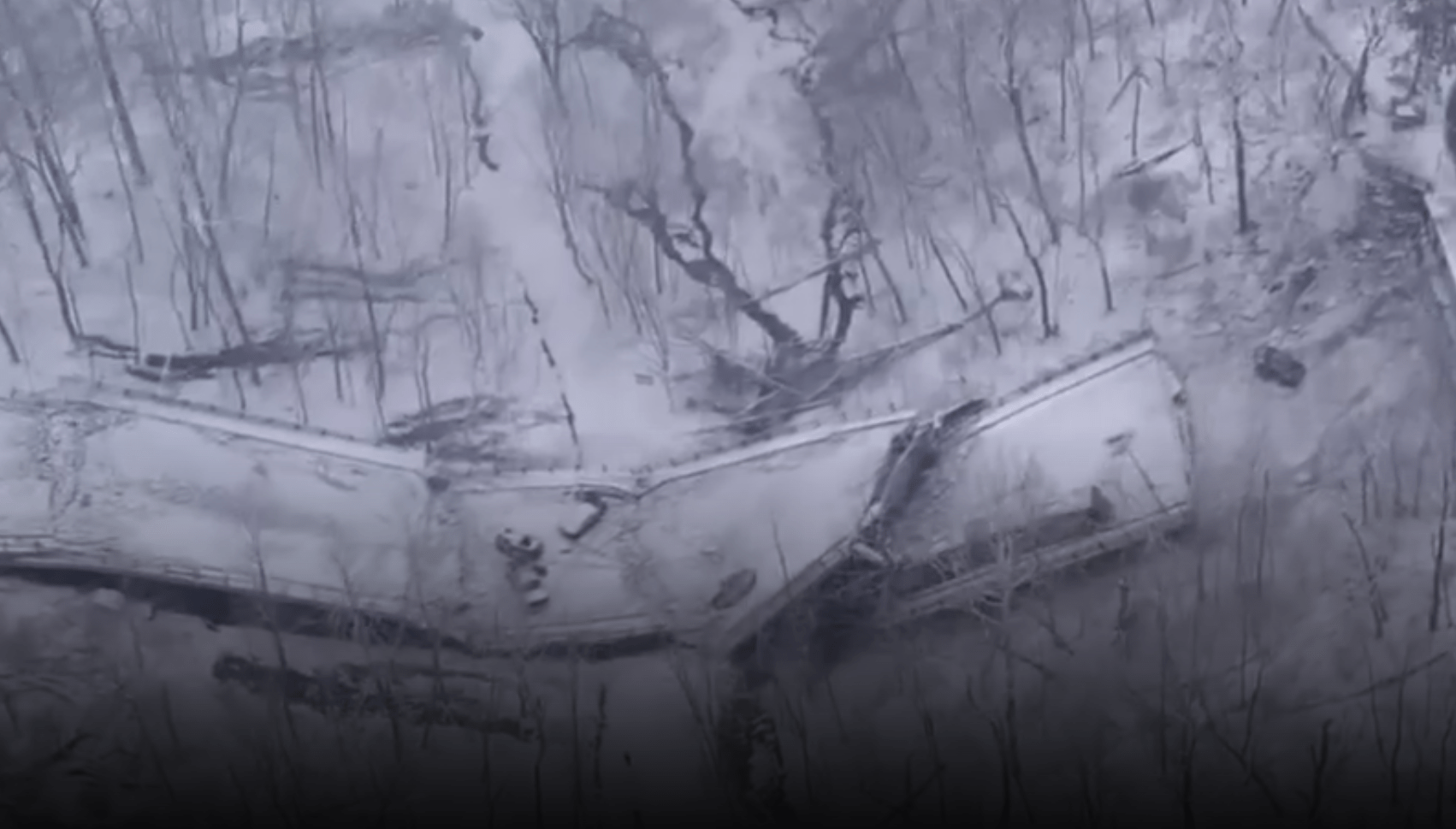

Ten people were injured early Friday morning in the collapse of the 52-year-old Frick Park Bridge, which had been listed in "poor" condition by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation since 2011. It would only have cost $1.5 million to reinforce, but transportation authorities didn't initiate the fix — nor have they completed work on the estimated 175 other bridges in surrounding Allegheny County that are also graded as "poor."

Yet in October 2021, a new $900-million, 13-mile beltway opened on Pittsburgh's suburban fringe, despite the fact that the metro area population has declined for seven years straight. Between 2009 and 2014, Pennsylvania spent just 22 percent of its capital expenditures on road repair and 29 percent on road expansion, with the remainder devoted to other capital projects.

@Pgh311 I hope someone is keeping an eye on the underside of the Forbes Avenue bridge over Frick Park? One of the big "X" beams is rusted through entirely (and, yes, I see the cables, so it's probably not a crisis). pic.twitter.com/UQScawPEGQ

— Dr. G Kochanski (@gpk320) December 29, 2018

The City of Bridges isn't the only city that's failing to maintain some of its most ubiquitous infrastructure. Nationwide, about 7.5 percent of bridges received a "poor" grade in 2019, and 47 percent were scored as "fair," despite decades of autocentric transportation policy that's directed vast sums to highway agencies that could have repaired much of the damage.

Advocates say that's partly because states spend an average of just 30 percent of capital funds on maintenance, while spending 29 percent on new lane miles that only increase their staggering backlogs of badly broken roads. Federal policy currently requires states to consistently measure their infrastructure's state of repair, but not to actually fix the damage they find before they build more — a loophole that advocates hoped to close when the country's core federal transportation programs were reauthorized last year. But the transportation bill that finally passed Congress, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, doesn't contain a fix-it-first requirement for the historic $110 billion in formula grants specifically earmarked for roads and bridges.

SIDEBAR: STREETSBLOG SCRIBE SHARES HIS HORRIFYING PAST WITH THE FRICK BRIDGE

At a Pittsburgh event held just hours after that bridge collapse to celebrate that law, President Biden remarked on the nation's "mind-boggling" bridge repair backlog, pledging that "we’re gonna fix them all." But the new $26.5-billion Bridge Formula Program carveout included in the bill will still allow states to use those dollars for bridge construction in addition to maintenance — and some industry groups estimate that repairing every bridge in America would take at least $42 billion, even if new highways weren't cannibalizing federal funds.

"More money won’t solve the problem if it’s not paired with the appropriate policy reform," said Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress. "The federal government has given the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation an enormous amount of money. The question is, what are they deciding to do with it? Because we know they’re not prioritizing repair enough."

Just awful. I sincerely hope everyone involved fully recovers. pic.twitter.com/dIf3CmZSp1

— Kevin DeGood (@kevin_degood) January 28, 2022

With the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enshrined into law for the next five years, advocates will now need to pressure their state transportation leaders to spend their federal funds on repair rather than expansion — and not let them pass the buck when they claim they can't help with local maintenance priorities. DeGood points out that under the policy known as "uniform transferability," state and local agencies can legally redistribute federal funds to one another, which means the Pennsylvania DOT could have helped the Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure to fix the Frick Park bridge if the agency considered it a higher priority than, say, yet another boondoggle airport beltway.

"Don’t let anybody tell you, 'Oh, this is a city bridge, it's not our problem,'" he added. "States always claim poverty, and they also claim that somehow, there’s strictures that prevent them from doing repairs. That’s not the case. These are political decisions that have been made by generations of transportation officials."

When it comes to the incoming flood of federal highway money, DeGood says Pennsylvania could spend the estimated $11.3 billion it will receive from Washington on completing its repair backlog. But unless advocates speak out, the state probably won't.

"Unfortunately, history strongly suggests that states will not prioritize repair," he said. "This [bridge collapse] is not a thunderbolt that came out of the blue sky. This is the result of a system that lacks accountability...We can look out across time and see when better policies around repair would have prevented catastrophe. This is one of those times."