The Democrats are getting creamed over the price of gasoline — and it’s not really fair (though it sort of is, too).

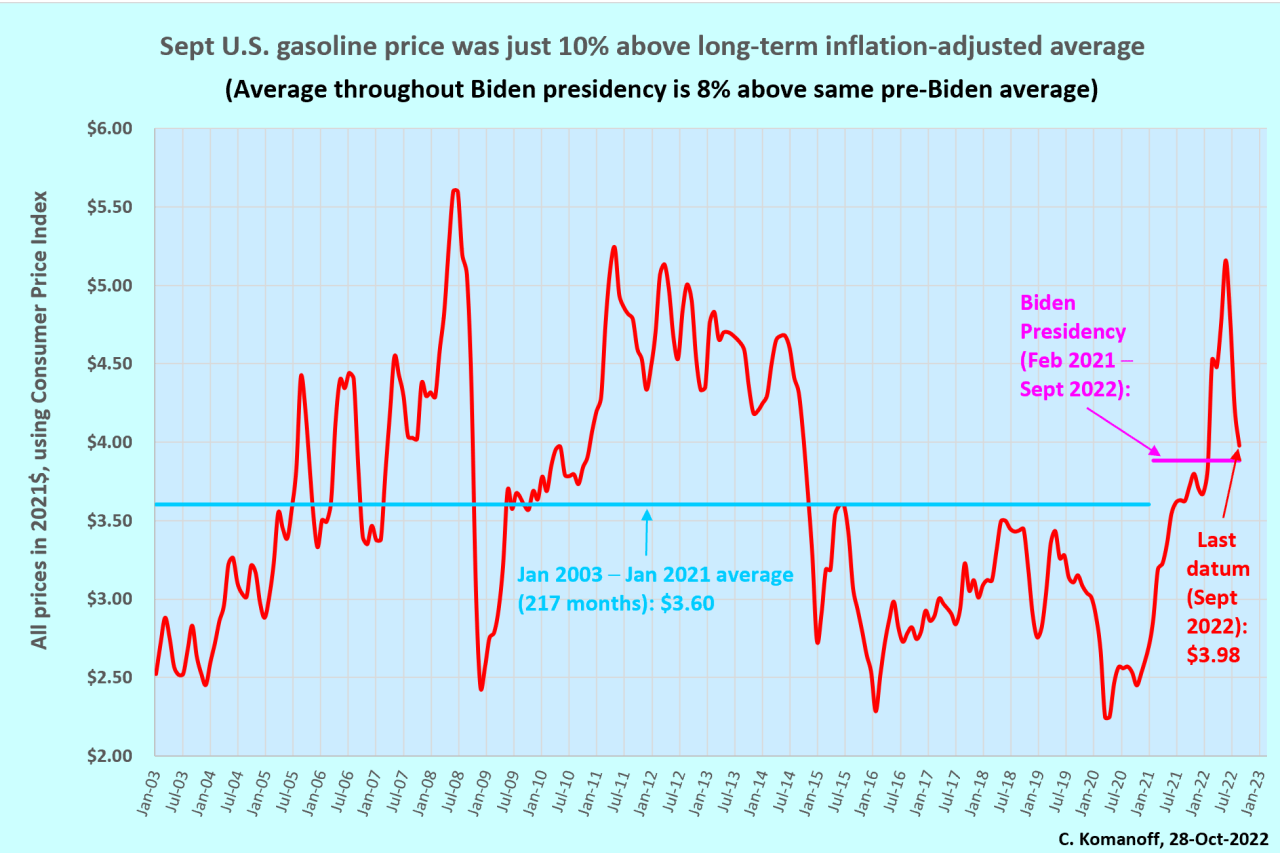

First, let’s look at the unfair part of this — the prices. The average cost of a gallon of gas sold in the U.S. did indeed double from $2.56 in February 2021, Biden’s first full month in office, to a record $5.15 in June.

The price has fallen by more than a buck since then, settling in at $3.99 for September, but nonetheless, the mainstream media — including The New York Times in its story last week, Why the Price of Gas Has Such Power Over Us — keeps depicting gasoline prices as a murderous asteroid about to slam into the midterms because high-priced gasoline is wrecking household budgets.

If only Americans could see today’s prices in their historical context. This chart of monthly average gas prices over the past two decades shows that across Biden’s presidency, and, crucially, adjusting for overall inflation, gasoline has only cost 8 percent more than it did in the prior 18 years. Similarly, the price in September was just 10 percent above that inflation-adjusted long-term average:

Of course, historical context doesn’t go far with working people who are struggling. And that’s where the Democrats — as well as Republicans who are demagoguing the issue — bear blame. And it’s no surprise that media outlets reporting on “high” gas prices are missing the point.

Take the Times piece mentioned above. Its failure is not in solid reporting, but in its framing and who the reporters choose to quote — like this guy from the price-tracking service Gasbuddy, whose name should tell you everything you need to know. “When [gas] prices go up,” the gas buddy says, “we have this feeling of oppression that we can’t do everything we want.”

The truth? We — and by “we,” I mean Democrats, Republicans, unaffiliateds and pretty much everyone except Luddites — created an entire society built on that oppression.

This is clear from the life story of one of the casualties quoted by the Times, Denange Sanchez, a 20-year-old who, when not studying medicine at Eastern Florida State College, helps her mother clean houses and apartments on Florida’s East Coast.

Denange told the Times that she and her mom “fill their tank three or four times a week driving to apartment complexes and private homes.”

Hearing that, most of us will simply roll our eyes and blame the Sanchezes for buying an unsustainable, over-sized SUV.

But when I reached out to Denange Sanchez, it became abundantly clear that she’s a victim of an America she didn’t make, but is nonetheless stuck with. Rather than a big SUV, she drives a Ford Fiesta, a modest hatchback that averages a decent 30 mpg.

So why do they need so much gas? Simple: America.

Denange lives in Palm Bay, which is on the Atlantic coast dead middle between Jacksonville and Miami. It’s not a particularly prosperous town, which in America means that its schools are sub-par. As a result, Denange told me in an interview, her mother drives her younger sister to a specialized school 40 minutes to the north in Viera.

“The school is known for its academic success,” Sanchez told me. “My mother wanted to make that sacrifice to instill a better future for my sister. Not only is this far, but we’re doing it nearly every single day which is why we are spending so much on gas.” (Though they’re also having to fuel the pickup that the mother needs for her new landscaping business.)

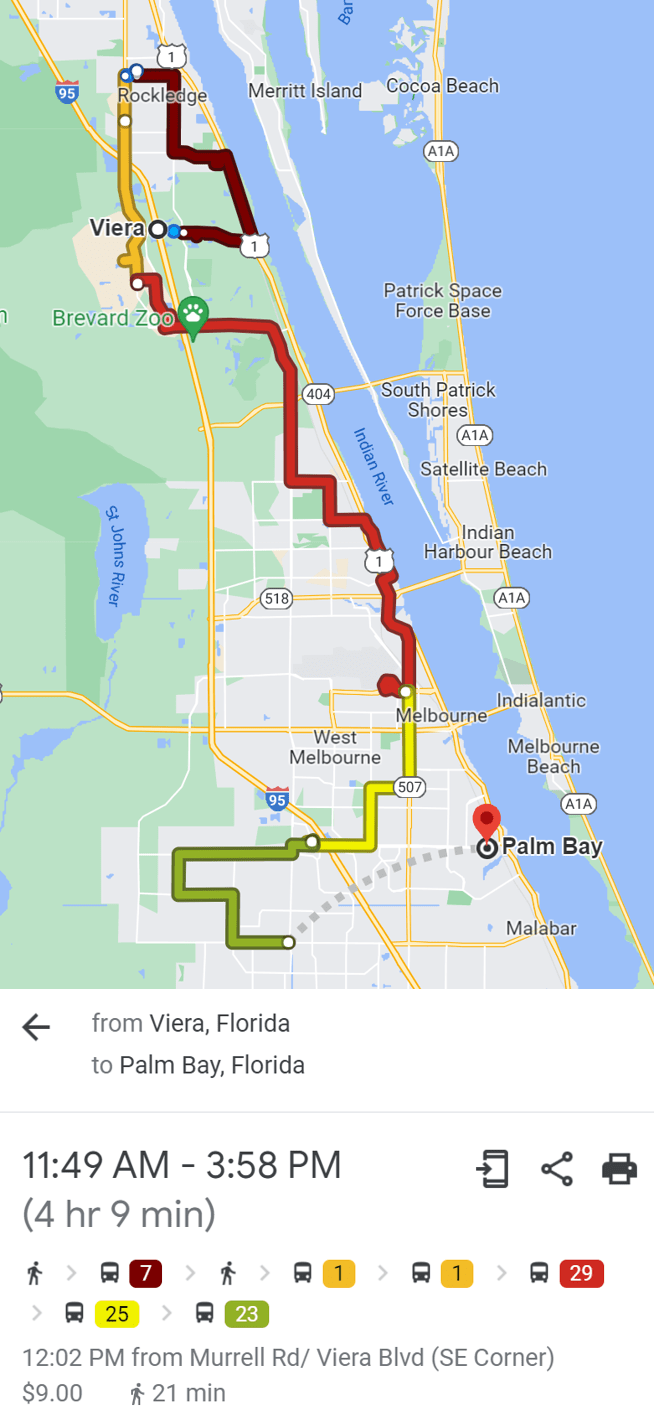

I checked Google Maps. It’s 22 miles from Palm Bay to the school in Viera. Don’t try to get from one city to the other via public transit; I checked Google Maps for any semblance of a bus schedule: The “ride,” including a mile of walking, takes four hours and would cost $18 round trip.

How about carpooling to Viera? Sanchez pointed out that most of the students who attend the affluent school live very close to it, while those who live in Palm Bay are mostly stuck with lesser-quality schools.

Heaven forbid that Palm Bay, a struggling city in the same county as Viera, be granted state funds to upgrade its own schools — under Gov. Ron DeSantis, that’s not going to happen. Then again, school-funding equity has remained stubbornly out of reach in New York and other supposedly progressive bastions.

Another solution, of course, would be for affluent Viera to democratize its zoning to allow fourplexes or other affordable housing so that striving families like Denange Sanchez’s can attend its top-quality schools without punishing commutes.

None of that, of course, was mentioned by the Times, despite the fact that in another recent story the same reporter bemoaned the difficulty of building affordable “starter homes” due to exclusionary zoning. (The reporter did, at least, include a glancing reference to how America has built “sprawling communities [with] scant public transit,” though it was presented as completely normal.)

That was also true in another Times story on gas prices from two weeks ago. That one featured Christina Pixton, a 37-year-old married mother of two who works the night shift at a UPS warehouse in Reno. She spends “$70 to $80 a week to fill up her Toyota Highlander.”

That tab seems accurate, given the reported $5.75 Reno pumps — California air quality rules make gasoline unusually expensive in bordering areas of Nevada. My back-of-the-envelope figuring suggests she’s driving her Highlander 300 to 350 miles a week.

Thanks to the America that Pixton lives in, she’s stuck behind the wheel. A carpool or commuter van would help, but UPS’s imperious scheduling practices render those nearly impossible, as Pixton makes clear on this Teamsters Local 533 podcast. (She’s a Teamster shop steward fighting for a semblance of worker autonomy.)

The mediocre fuel mileage of Pixton’s Highlander doesn’t help. With, say, a Corolla, like the one I rented for a road trip last month, she would cut her gas bill by a third. Still, the crusher, in my view, is the crummy $19 an hour she earns her from UPS, along with our country’s profoundly inequitable taxation that effectively takes a larger piece out of Pixton’s paycheck than it extracts from the coffers of America’s billionaires.

Every shift Christina Pixton works costs her an hour or more in commuting time and 10 bucks in gasoline. Higher wages and fairer taxation wouldn’t change that, but they would make those burdens feel a lot lighter. Gasoline weighs heavily not just from its cost but because financially squeezed working people have no margin to manage wildly fluctuating pump prices.

Gasoline isn’t just a budget-buster. It’s a climate destroyer, accounting for nearly one-fourth of U.S. carbon emissions. This year it became a geopolitical weapon with which Russia hopes to crack European solidarity for Ukraine. And right now its price looms large in the midterms, which doubtless influenced Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to cut production just when Democrats were upbeat about their chances of holding the House and winning some breathing room in the Senate.

There is relief in sight — if you look far enough ahead. In August, Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act, an omnibus bill that by accelerating the shift from combustion to electric vehicles augurs a lesser political weight for gasoline over the long haul.

Too bad this relief can’t come in time to be a difference-maker next week. Too bad as well that this big legislative achievement goes unmentioned in the press, which would rather make hay from Biden’s ignominious (and ineffectual) groveling before Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, which came before the Democrats passed the IRA (with not a single Republican vote).

So now the Republicans are surging, fueled in part by media malfeasance on the true cost of gasoline and the uniquely bipartisan nature of this particular American tragedy.