How and where we plant street trees impacts the quantity and quality of benefits we get in return such as how cool our streets feel during hot summer days, and how efficiently trees can filter rainfall and serve as stormwater management infrastructure.

At the block level, at least 40 percent of surface area should be shaded under tree canopies to counteract the heat-absorbing effects of asphalt streets and rooftops, according to a 2019 study by the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Being strategic in how we allocate space for these natural resources is a key factor for climate resiliency efforts.

This September, the City of Boston released its Urban Forest Plan, a 237-page document outlining the city’s long-term strategy for adding trees throughout the city in an equitable and sustainable way, part of its larger climate change agenda.

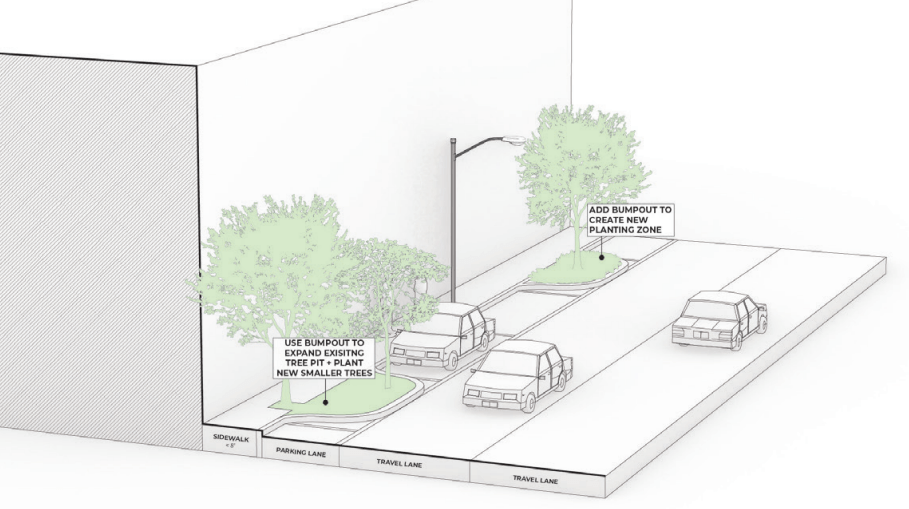

Acknowledging the constraints of limited space throughout the city, the plan recommends planting trees in the street as a possible workaround: “on-street parking represents a significant amount of surface area that can be used for creation of bumpouts or other means of providing new planting sites or higher quality planting space for existing trees.”

In the city’s Heat Plan, an action plan to prepare for the near-term and long-term impacts of extreme heat in a changing climate, people reported a lack of trees and the presence of “lots of pavement, concrete and asphalt” as the top two reasons for why their neighborhoods feel hotter.

As the effects of climate change begin to worsen, replacing heat-absorbing pavement with new trees can help make a difference toward expanding our urban canopy when space is limited.

Where we plant trees and how many we plant in a specific area also matters.

Citing poor historical urban planning practices across Boston neighborhoods, equity is listed as the first goal in Boston’s forest plan: ”focus investments and improvements in under-canopied, historically excluded and socially vulnerable areas.”

However, Boston’s Urban Forest Plan avoids setting any measurable targets that would help advocates hold the city accountable to meeting these goals. The plan’s authors acknowledge this outright: “(these goals) do not lay out specific numbers, such as a percent canopy coverage, that can be quantitatively measured to understand progress toward these goals,” they write.

A number of other cities are already taking steps to replace underutilized pavement on city streets with new tree plantings.

In Portland, Oregon, a pilot program will add bump-outs with trees in East Portland, a part of the city which currently has a small tree canopy and “experiences higher temperatures during heat waves, which are expected to worsen as our climate changes.”

“By creating space along roadways for large trees, the pilot intends to provide natural stormwater management and life-saving shade and cooling,“ according to a project bulletin by the Portland Bureau of Transportation.

Portland has already documented and released bump-out guidelines in their Pedestrian Design Guide, which includes considerations such as street type, whether on-street parking or other curb zone use is present, and whether existing sidewalk space can accommodate the needed quantity of soil or stormwater facilities.

The @CityOfBoston's new forestry team should take a leaf or two (or even a whole tree!) out of Providence's (and the @WBNApvd's) book when it comes to tree pits - parking lane tree pits make sense on side streets and in neighborhoods because they calm traffic and shade streets. pic.twitter.com/yBfdZ9bO4p

— Matthew Petersen 🚎🌇🏳️🌈 (@meptrsn) October 3, 2022

Closer to the hub, Providence’s streets are also welcoming trees as part of a larger effort to increase the city’s tree canopy, according to Alex Ellis, Principal Planner with the City of Providence. Sycamore and Messer Street, two adjacent streets have trees in the parking lane following requests by the West Broadway Neighborhood Association.

In addition to environmental and climate resiliency benefits, trees also affect traffic, helping make streets safer for people by visually narrowing the street and slowing down cars.

To support this connection between trees and transportation, Boston’s plan calls for agencies at the municipal and state levels to “ensure that major corridor reconstruction projects consider trees as a critical component of transportation infrastructure.”

“Trees are key to walkability and bikeability, shading the public rights-of-way and reducing heat levels, which is especially impactful for pedestrians and cyclists,” states the Urban Forest Plan.

Planting trees in the street could also relieve some of the stress tree roots experience as people continuously step on sidewalk tree pits, compacting the soil.

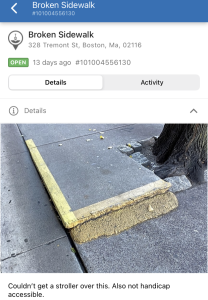

Compacted soil smothers tree roots and forces “tree roots to grow towards the surface in search of air and moisture,” according to a report by the Environmental Protection Agency. “This often results in the common problem of sidewalk upheaval as roots grow upward to reach all important oxygen and water.”

Broken sidewalks are an accessibility issue for anyone using a wheelchair, pulling a grocery cart, or pushing a child on a stroller.

In Boston’s Urban Forest Plan, setting up a program to create bump-out tree plantings in the street is considered a mid-term priority, to be rolled out sometime within the next decade. But with similar projects already happening across the country and the world, Boston can build off what already exists.