Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Housing, mobility, public transit, metros, bike lanes, pedestrian-scaled urbanism–one would be hard-pressed to find a city in the world that rocks these issues better than Copenhagen. That’s why SPUR, now that it’s back to its annual urban education trips around the world, sent a delegation to that city to learn about how they got things that the Bay Area can only dream of, such as a bike modal share of 38 percent versus the Bay Area’s 1.7. “We’re trying to create a car-free city,” explained JRDV Urban International Architecture’s Morten Jensen, during a SPUR talk about last July’s trip. “It’s not completely car-free, but we’re trying to enhance the center by being a bicycle and pedestrian city.”

It wasn’t always this way. As with American cities and other cities in Europe, Copenhagen turned hard towards sprawling suburbs and cars in the post-war period. It was all about suburbanization after WWII, said Jensen, who splits his time between the Bay Area and Copenhagen. “It was the dream to live in your own house and have your own yard.”

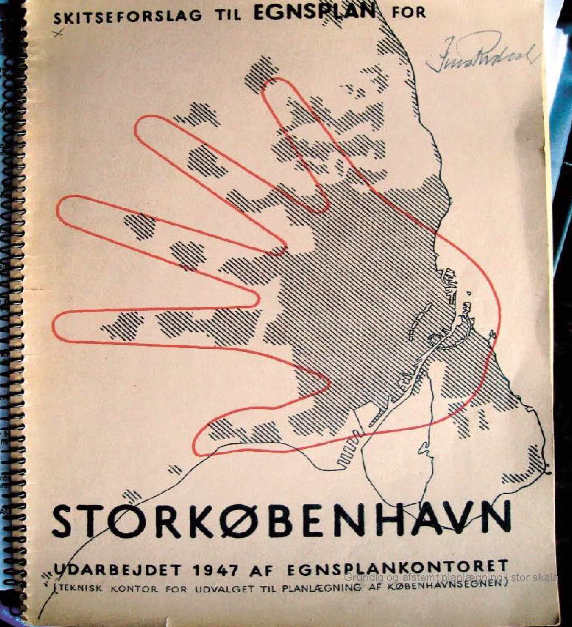

So Copenhagen began to develop suburbs around its five commuter rail lines, as seen in this 1947 suburban hand-shaped development plan below:

But, as with other cities, this had unforeseen, negative consequences. It hollowed out the urban core, which was left with deteriorated apartments, elderly who couldn’t afford to move, and students. Meanwhile, the shipping industry, which had been key to Copenhagen’s economy, was moving to Asia. Basically, the city was losing its entire tax base.

The city started looking for ways to bring wealth back into the downtown. They started by building new transit lines to an undeveloped part of the city that had been a military base.

“They had a crisis and they decided on a way to solve the crisis,” said Jensen. “This started the ‘Copenhagen model.”

The result, over 20 years later, was 15,000 new housing units, a university, and new jobs, mostly created by a corporation. This brought new “taxpayers, who paid off loans, and then there was money to spend to redevelop other areas of the city.”

The new tax revenue lead to further expansions of the metro and the redevelopment of some of the former ship-building, waterfront industrial areas into even more housing. But all of this was done with a priority on public space, pedestrian spaces, and building for bicycles, not cars, as seen in the lead image.

“It paid for the bicycle network. We took areas previously used for cars and parking and turned them into bike lanes and pedestrian plazas,” said Jensen.

Bloxhub’s Martine Reinhold Kildeby, another of the Copenhagen-based speakers, stressed that making these spaces work meant focusing on the experience for people living there and then working back from that towards urban and engineering designs (the opposite of American traffic planners). “Look into the future at what you want to create and then look to solve solutions at the same time,” she said. For example, people generally enjoy urban spaces rich with trees, greenery, and as much nature as possible. “The forest and the river and the squirrel should be at the table” when making plans, she said.

It also means sometimes having to fix developments that don’t quite achieve that. For example, she talked about an early attempt at building housing in the former shipbuilding areas. Homes were constructed right up against the water. That’s nice for the people in those housing units, but it also cut off others from the waterfront. To resolve that, the city built “bridges right on the water so people could walk around over the water. The solution is even cooler than it was before,” she said (see lead image).

And that people-first, experience-first approach is helping Copenhagen approach its goal of zero carbon emissions to boot.

Of course, some of these ideas, at least in principle, are incorporated into San Francisco’s developments–think of Mission Bay, with its new transit and waterfront housing. But San Francisco seems to do things piecemeal, without a unified vision. “In the Bay Area we rely on very complicated public-private partnerships that are smaller in scale,” said SPUR’s Sujata Srivastava, who was on the trip. “We do not do as good a job at capturing the value and redirecting it. We have the same intentions, but we don’t do it at the Danish scale.”

In addition, Danish and European regulations clear projects if they’re reducing CO2 emissions, so that cities can, for example, sprinkle windmills throughout.

“The only real regulatory document we have in the Bay Area is the California Environmental Quality Act, which doesn’t even really look at carbon emissions impacts,” she added. “So it’s often used to stall projects that could lower carbon footprints.”

Srivastava suggested that the place to start reforming California and emulating the Danish success story would be to reform CEQA to prioritize carbon emissions, so regulations don’t stand in the way of developing people-scaled cities. “The Bay Area has really similar goals,” added Jensen. “The difference is in getting it done.”

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.