For decades, a little known Caltrans advisory committee dominated by highway and automobile interests has been setting the design standards for signs, signals and pavement markings for California's urban streets. If a city wants a green bike lane, it has to be approved by the California Traffic Control Devices Committee (CTCDC), which also develops the state's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD).

The problem, say advocates and city transportation planners, is the committee, which only meets three times a year, doesn't include representation from all road users, and requires such an arduous process to do something innovative that many cities don't even bother. It's chaired by a manager of the Automobile Club of Southern California (AAA).

"Essentially what you have are no road user groups participating in decisions about traffic control devices that are meant to control the behavior of all road users," said Jim Brown, the communications director for the California Bicycle Coalition (CBC).

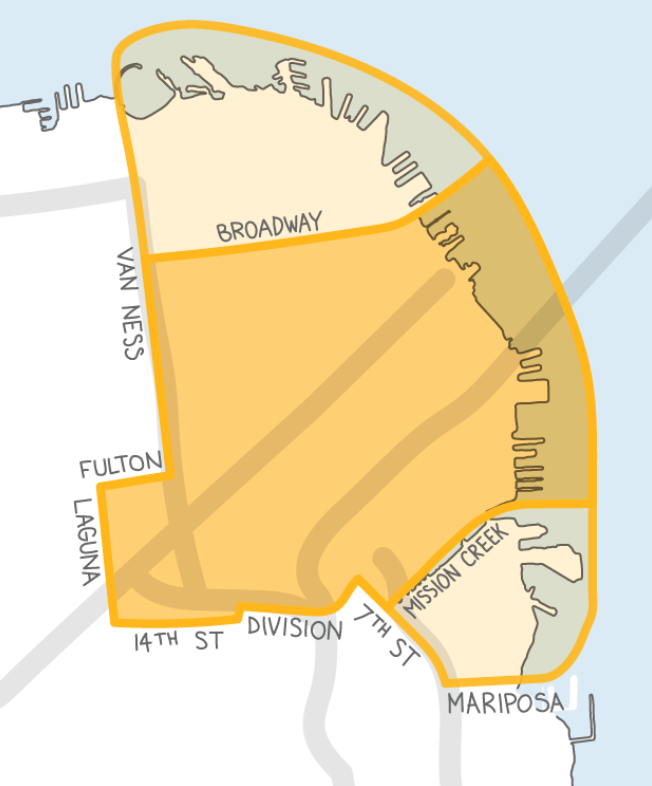

An agency can get around the state process by getting approval for an experiment from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), which sets federal standards, but it still has to get CTCDC backing to make a treatment permanent. Green bike lanes that have been installed in cities like San Francisco and Long Beach are considered trials, and have not gotten the state's official blessing.

"We need to open up this idea of a state highway function dictating the design standards and the traffic control devices for urban streets," said Timothy Papandreou, the deputy director of transportation planning for the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). "There are unique differences on urban streets."

A bill working its way through the Legislature and being pushed by the California Bicycle Coalition would require the CTCDC to consult with groups representing "bicyclists, children, persons with disabilities, motorists, movers of commercial goods, pedestrians, users of public transportation, and seniors."

It's the beginning of a process that the CBC hopes will lead to the state adopting bike standards similar to the recent bikeway guidelines adopted by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), which incorporated best practices from all over the world. Caltrans is currently working on updating the state's MUTCD and has adopted a complete streets policy.

"If we could get California to adopt these guidelines as a standard, then cities could try some of the facilities that are reflected in that guide with the protection that comes from doing something that has been endorsed," said Brown. "It's the lack of endorsement that makes communities reluctant to give things a shot."

Liability is also one of the main concerns that prevents cities from moving forward with innovative street treatments, said Ryan Snyder, a Los Angeles-based transportation consultant and longtime bicycle advocate. He feels it is sometimes overblown, though.

"The first thing lawyers for the plaintiffs always ask is 'did you follow established standards and guidelines'? If you don't, the chance of a city losing a lawsuit is pretty high," said Snyder. At the same time, it's good to experiment, gather data and be cautious before establishing a standard because "there have been a lot of mistakes made in road design," he added.

The SFMTA's Papandreou worries that if the California standards aren't changed soon, San Francisco will have trouble meeting its goal of making 20 percent of all trips by bicycle by 2020. That's because obtaining state and federal funding for innovative treatments such as green bike lanes can be difficult if the treatment is not a recognized state standard.

"In all of our understanding of what gets people to ride their bicycles it's really about design, and the design on the street. Funding aside, I'm not sure how we're going to meet the 20/20 goals unless we put out more innovative designs," he said. "It's what creates that ridership and allows people to ride their bicycles."