Though I bicycle, walk and take transit for half my trips, the other half, which usually involve shuttling children in carpools, for now necessitate driving a car. So there are days when I am on the streets of San Francisco behind a windshield, sometimes for hours, negotiating city streets. I know exactly how complex urban driving is and how aggravating congested traffic can be. And I grew up soundly in the midst of our car culture.

As a teen, I adored “Thunder Road." From Bruce Springsteen to Madison Avenue, our society glorified the status, freedom, power, identity, safety, protection and even redemption that cars offered. Cars were our Iron Man suit extending our physical abilities to unprecedented levels. We could eat, sleep, and live in them. Anyone over the age of 16—especially anyone male—without a car was a loser of the first degree, to be scoffed at and ridiculed. Given this heritage of the last sixty years, it’s not surprising that we Americans are now resistant to trading in our all-powerful motorized conveyances for a bicycle or a seat on the train.

Though times are clearly changing and an energy-scarce future means the internal combustion engine, with its extravagant inefficiency, will fade away, some people will continue driving no matter what. Especially people who are 55 or older, who have a substantial income, and who have a decent nest egg saved for retirement—some of them may indeed never ride a bicycle or take public transit.

So how to convince well-to-do, aging urbanites who will drive until their car keys are pulled from their infirm hands that it is in their best interest to support the creation of good, safe bicycle infrastructure that allows people ages 8 – 80 to bike confidently and without fear, especially when at times this infrastructure will come at the expense of car parking or a lane of car travel? Such reallocations of space strike a chill in many a car driver’s heart. There will be traffic nightmares! The economy will collapse! If more space is given to bicycles, before you can say "Harvey Milk," crazy liberal cities like San Francisco will outlaw cars altogether.

Or so the protestations go. But the truth is that even car drivers should welcome and support bicycle infrastructure. Here are six reasons why, drawing heavily from the theory of Other People.

1) Congestion is mostly caused by Other People in cars and will only grow the more Other People keep driving. When you drive in a city, what holds you up, slows you down, wastes your time, keeps you from where you want to go, are Other People. These Other People are sometimes on foot or bicycle, but mostly these Other People are in cars, though as car drivers we may not want to admit it.

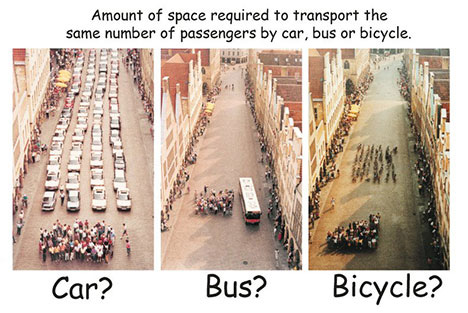

What we have to understand is that Other People in cars take up an enormous amount of space. Other People in cars are, in fact, the biggest hogs on the road by a factor of at least ten. In addition, as the cost of gasoline and other energy increases, people are growing more interested in urban living, so population density and congestion will continually increase in most cities until complete gridlock is reached and no car driver can get anywhere except perhaps in the dead of night. It has been proven worldwide that car infrastructure induces driving and bicycle infrastructure induces bicycling. If you want to have room to drive, inducing Other People to travel by foot, public transit, or bikes means a lot more room for your car. On space issues alone, as a driver you want as many Other People as possible not in cars. In addition, as the ranks of bicyclists are swelled by ordinary Other People who are more risk averse than the early-adopter cyclists (who had to be aggressive and even daredevils to cycle on car-dominated streets) bicycle traffic will grow more orderly, predictable, law-abiding, and calm.

But, you might counter, if Other People stop driving, then all cars will go away, and that can’t be good for me. On this point you can relax. Cars are not going away in our lifetime. Some dense, downtown areas might become pedestrian-only, but pedestrianizing dense downtown areas won’t impact 99 percent of driving trips (but it will make shopping or going to a restaurant downtown much more pleasant). If vast numbers of Other People stop driving, there may be some reduction in the number of lanes dedicated to cars on city streets, but since cars will still be useful for some activities, Other People will still own enough of them (or rent them via a car-share program) that roads will continue to be open to them for the foreseeable future. Road speeds may be a little slower to increase safety for pedestrians and bicyclists, but it’s not road speeds that slow you down right now, it’s all the traffic. Get rid of the traffic and even 20 mph will get you around swiftly.

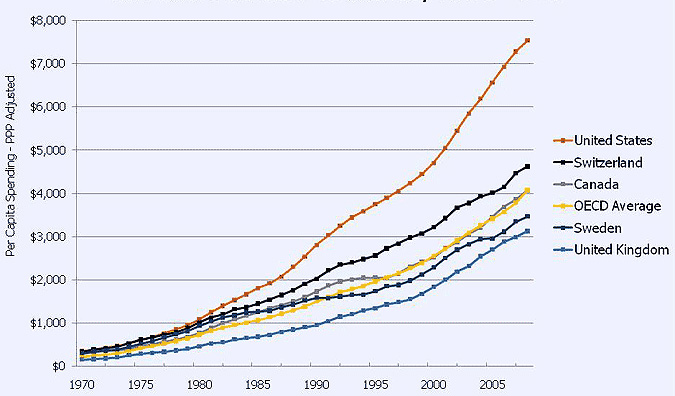

2) Healthier Other People cost you less. When Other People ride bicycles instead of drive cars, they are healthier due to the exercise, and all the people around them are healthier due to breathing cleaner air. This means that your city’s health care costs, the nation’s health care costs, and your health insurance premiums will all be lower. Obesity and diabetes are leading causes of skyrocketing health care costs. (In car-congested areas, we can add asthma to the list.) The more people drive, the fatter they are. Health care now consumes 17.3 percent of our nation’s GDP. (France, a weak runner-up in the Let’s-Destroy-Our-Economy-Via-Health-Care pageant, clocks in at a paltry 11 percent.) Skyrocketing health care costs are one of the prime reasons why small businesses are reluctant to hire new employees. Though there are many other pieces to the health care mess that need to be addressed, by making Other People less sedentary and their air less polluted, you will directly benefit economically. And in terms of getting sedentary people fit, integrating exercise into their daily activity via walking or biking costs one-fourth as much as getting them to go to the gym.

Providing safe routes for children to walk and bike to school is especially important to reduce epidemic childhood obesity rates, especially since 70 percent of obese children go on to become obese adults. In addition, children who walk or bike to school watch less TV and are less likely to smoke, girls who walk or bike to school have higher cognitive test scores, and children who are physically-fit have higher scores in math and reading than their less-fit classmates. More children walking and biking to school would also provide a huge benefit directly to drivers: right now parents driving children to school create 20-30 percent of morning traffic congestion in urban areas.

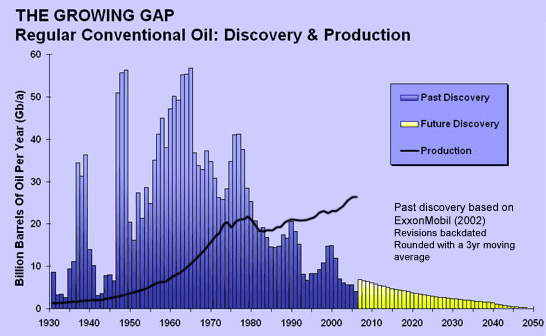

3) When Other People switch from cars to bicycles it improves the local economy. San Francisco, for example, benefits very little from money spent on gasoline, cars, and car insurance. And, as we all know, roughly half of our national trade deficit is due to importing oil. When Other People free themselves of the $8800/year cost of car ownership, they have a great deal more money to spend locally, creating an economic boost for your city far more powerful than a temporary tax cut or (unless you live near Wall Street) various iterations of the Fed’s quantitative easing. In addition, the less oil your city uses, the more your city’s economy will be impervious to the economically destabilizing effects of Peak Oil.

In the coming decades of tightening energy supply, the cities and regions that are able to produce the most GDP with the least energy will be the most resilient and stable. Even if you personally have the money to withstand economic crashes, a wealthier city with a healthier tax base will be a more pleasant place in which to live out your golden years. Last but not least, employees who bicycle to work have 15 percent less absenteeism than non-cyclist employees, making them more economically productive.

4) Good bicycle infrastructure encourages tourism. This concerns the ultimate Other People—tourists. Bicycling is a lovely way to the see a city, and parents especially appreciate an active, healthy way their whole family can participate in a vacation. San Francisco, for example, with all its natural attractions, could be a great city for tourists to bicycle in. Already the ride through Crissy Field over the Golden Gate Bridge to Sausalito is world famous, and an equally nice ride someday could take visitors up Market Street, through the Wiggle and on to the attractions of Golden Gate Park. But the bicycle infrastructure at present is not safe enough or simple enough or pleasant enough for anyone not girded for the teeth-gnashing rigors that bicycling in San Francisco currently entails. Cities with tourist-friendly bicycle infrastructure will find that tourists on bicycles are more likely to stop at shops along the way than tourists in cars or buses. And they will also find that tourists on bicycles are less likely than tourists in cars to kill or maim their city’s citizens as they try to negotiate complex urban traffic. (Anecdotal, I know, but the two times my family members have been hit by cars, both cars were driven by tourists.)

5) Bikes consume far less taxpayer subsidy than transit or car driving. Though it’s true that not all Other People can ride bicycles on all occasions, each time one of them does take a bike instead of a car it saves you money. Since gas taxes have not increased for decades, they cover only half the cost of road construction, maintenance and repair costs. General taxes cover the other half. (See the excellent report, Whose Roads? Also see Do Roads Pay for Themselves?) Factoring in the indirect costs of parking, crashes, congestion and land, cities also shell out $.28 for every mile driven on their streets. Bicycles, in contrast, cost cities one cent per mile traveled in indirect costs. To illustrate the point with data from Whose Roads?, let’s take two neighbors, Driver Dan and Biker Betty, who each pay $300 annually in local taxes that fund roads and traffic services. Dan drives 10,000 miles per year on local roads and also pays $24 in gas taxes that go towards local roads. The direct cost of his driving to the local community is $560 and the indirect cost is $2,800. Total cost of his driving to the public: $3,360. Net loss to the public taxpayer: $3,360 - $324 = $3,036. In contrast, Betty, who bikes 3,000 miles in a year and pays no gas tax, costs the city $48 in direct costs and $30 in indirect costs. Total: $78. Net gain to public taxpayer: $300 - $78 = $222. It's pretty clear who is the better deal for the public purse.

Then there’s the amount taxpayers subsidize each gallon of gas through federal subsidies of corn, ethanol and oil companies that comes to $13.3 billion/year or $.10/gallon. (Corn subsidies = $3.6 billion/year, ethanol subsidies = $5.7 billion/year, tax breaks to oil industries = $4 billion/year.) And there’s also the largest military in the history of the world controlling the oil supply in the Middle East and North Africa, so Other People can have cheap gas. (If we estimate half of the US defense budget goes toward oil procurement—$331.9 billion—and divide that by U.S. consumption of oil—132 billion gallons, it comes to $2.51 for every gallon of gas put into an American gas tank.) You would be far better off with Other People paying the true cost of gas, which would result in lower taxes for you (perhaps as much as 25 percent less) and fewer cars on the roads. You would be far better off economically if most freight were moved by rail, and roads were routinely tolled based on road damage inflicted by a vehicle’s weight. When the true cost of any kind of energy is masked, people continue to vastly undervalue things like efficiency, make poor investments in energy-squandering ventures such as far-flung suburbia, and fail to make investments that are truly economic like rail. If you drive less than the average American and pay more taxes than the average American, you should wince every time you see Other People filling their gas tank up because you are footing nearly half the true cost.

Even as Other People consume less oil, the price of gas will still climb due to Peak Oil and the Export Land Model (rising internal consumption of oil in oil-producing countries will sharply curtail their exports) but if you are wealthy, gasoline still won’t be entirely beyond your reach. Whereas, if oil continues to be subsidized in the face of declining supply, shortages will be inevitable due to the lack of an appropriate price signal to decrease demand. Contrary to what oil and car companies would like us to believe, if gasoline reflected its true costs (not even factoring in the damage it does to the environment) the economy wouldn’t end; we as a nation would adjust our economy to reflect reality. Masking reality doesn’t make reality go away—it only delays the inevitable at tremendous cost that we pay for one way or another, even if we refuse to acknowledge it.

In terms of road repair and maintenance, bicycles are preferable to buses because their negligible weight inflicts a micro-fraction of the damage. (Light rail, while requiring more initial upfront investment, is also far easier on the roads.) Compared to maintaining roads, subsidizing oil, or building out transit, bicycle infrastructure is cheap, cheap, cheap. (For $75 million you could put in over a thousand miles of bike lane, say one that stretched from Los Angeles to Seattle. Or you could repave 3 miles of Interstate 710 in Los Angeles. Or you could rebuild about half (1.6 miles) of San Francisco’s Market Street. Or you could install 1.15 miles of high speed rail in California. Or you could extend Washington D.C’s Metro a little less than one-third of a mile towards Dulles Airport.) Of course, offering public transit that’s pleasant, frequent and reliable will be an important way of encouraging businesses to locate in your city to keep your economy afloat, but the more you can get Other People to bicycle, the lower the taxes you will have to pay for transit, roads and other transportation infrastructure. In addition, bicycle infrastructure also gives a city an edge in wooing companies over its car-centric counterparts. The city of Chicago is putting in bicycle infrastructure precisely because it attracts high tech start-ups with bike-riding employees.

6) Other People become happier, more energetic, more empowered and more connected to their community when they ride bicycles. How this might benefit car drivers may not be obvious, so let me explain. When Other People ride bicycles, they begin to feel better along a number of measures. Their health improves, they have less stress, they have more money to spend, they need to use less pharmaceutical drugs with all their debilitating side effects, endorphins are released naturally, and they being to feel empowered and self-actualized. Cars may make people feel psychologically powerful and privileged, but it is actually a physically inactive, enervating form of transportation that undermines basic self-reliance.

Driving a powerful car can be thrilling, but in the end the power belongs to the combustion of gasoline, not oneself. Most people cannot repair or modify their cars and must take them to a specialist, whereas bicycles are simple enough to allow mastery of their basic mechanics and further feelings of competence. And because in a car Other People are locked away from both their environment and their fellow citizens, car use tends to make them much more alienated than bicycle use. Without the armor of a car, Other People on bicycles are more vulnerable, but this means they also have more visual and physical connection with both their fellow human beings and their environment. There is no anonymity to screen their actions, no hiding who they are.

Like it or not, we are all interconnected, and the well-being of others affects our own. Biking is an inherently pleasant and easy activity that most people find enjoyable, so it’s not surprising that the top cities for bicycle commuting are also the cities with the top levels of happiness and well-being. In general bicyclists are a pretty happy bunch as long as they have smooth pavement, not too many stops, and aren’t physically threatened or intimidated by cars. The beauty of well-designed bicycle infrastructure is that it reduces the conflict between car drivers and bicyclists, leaving everyone more peaceable.

The plain, simple bicycle is one of the most efficient machines ever devised and one of the best tools we have to prosper in a lower-energy future. (And for people who live on hills, adding an electric-assist is also very energy-efficient, if not quite as simple.) Bicycles induce good health. They create self-reliance that can expand to other areas of people’s lives. They are cheap to own and operate. They free up money for the local economy. They do little damage to our expensive roads. They don’t take up much space. They don’t pollute the air. They increase people’s feelings of well-being. Their infrastructure is the cheapest of any form of transportation, including walking, and requires the least subsidy. They are fundamentally empowering and democratic.

Repurposing some city space now dedicated to car storage or car travel to bicycle infrastructure may seem like it will induce congestion, but it is a proven way to get Other People to convert — happily -- to bicycle riding in droves. Unhappy conversions through rising gas prices or shortages under conditions of bad or no bicycle infrastructure will result in unhappy Other People who are likely to make you unhappy in a multitude of ways. Based purely on enlightened self-interest, urban car drivers stand to gain much from the installation of bicycle infrastructure in our cities.

Karen Lynn Allen is the author of Pearl City Control Theory, a novel of city Buddha-mind walking, love, and breaking free (Cabbages and Kings Press, 1999) and Beaufort 1849, a novel of antebellum South Carolina (Cabbages and Kings Press, 2011). She lives up a big hill in San Francisco and rides her Xtracycle cargo bike (with an electric-assist) for utility trips and her regular (non-electric) bike to get around town.