Swamped by demand for safer streets, the SF Municipal Transportation Agency has been working to overhaul the way it delivers speed humps, sidewalk bulb-outs, chicanes, and other measures proven to tame traffic speeds and save lives.

By next spring, the SFMTA intends to implement its revamped traffic calming program, which was put on hold this year while planners streamlined the implementation process. The change was necessary to address a massive backlog of traffic calming requests that were often left unaddressed for a decade or more.

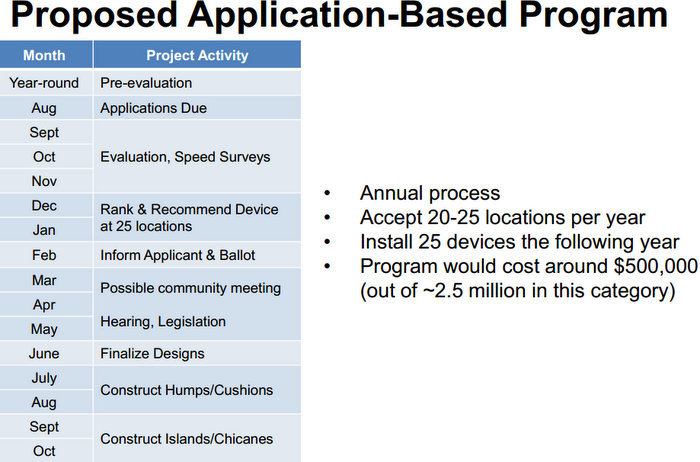

SFMTA planners say the new traffic calming prioritization program would be more efficient at targeting the neighborhoods with the most severe speeding problems and deliver low-cost improvements like speed humps and traffic islands with as little as a year from when it accepts an application to implementation. Miriam Sorell of the SFMTA's Livable Streets Subdivision outlined [PDF] the new process to a committee of the SF County Transportation Authority Board (comprised of the Board of Supervisors) on Tuesday.

Under the past approach, a resident's application for traffic calming, if accepted, was placed on a waiting list and ranked based on the severity of the speeding problem in a neighborhood. When an application reached the top of the list -- which was hard to predict, since a new, higher-ranking application could always displace an older request -- it would be grouped with other applications from neighbors to form an area-wide plan, and the SFMTA would hold community meetings to ask neighbors which type of traffic calming measures they preferred. As more requests were lumped in with others, Sorell said, small projects grew larger, delaying implementation. Meanwhile, improvements like speed humps, which should be quick and cheap to implement, would go through excessive traffic studies and community meetings.

Constrained by limited funding and staff, the SFMTA can only implement 20 to 35 traffic calming "devices" per year, with a current backlog of $9 million in plans ready to hit the ground in the next five years. Sorell said planners hope the new process will allow them to better prioritize improvements for the areas where they're needed most.

"We recognize that there's got to be a better way to do this," said Sorell. "It takes a long time to get traffic calming in your neighborhood, and there's a lot of confusion for residents in terms of where they stand and whether there's going to be something coming soon... We often end up promising more than we can deliver in a reasonable time frame."

"For too long, the whole traffic calming system has been slow, confusing, and frustrating," said Elizabeth Stampe, executive director of Walk SF. "Residents apply, are told yes, and then left in limbo for years. Even worse, the system has been totally reactive and ineffective. The streets where speeding is worst, the arterial streets, the most dangerous streets, have been ignored."

To simplify the process for residents, the SFMTA plans to get rid of the waiting list. Instead, said Sorell, planners would select a yearly round of projects based on the severity of speeding and crashes. If an application doesn't rank as a top priority, but does meet the minimum threshold for consideration, it would be placed on hold for two years. If the application still doesn't reach priority ranking within two years, the SFMTA would drop the application.

For local street zones, the focus would be placed on delivering low-cost traffic calming treatments like traffic islands, traffic circles, chicanes, and speed humps. At roughly $7,000, a speed hump costs one-tenth as much as a corner bulb-out, and requires minimal planning.

Corner bulb-outs, meanwhile, would be used more on arterial and commercial streets than local streets, said Sorell. "In some ways, they're less appropriate for a residential street that has very low pedestrian volumes," she said. "They make more sense as part of our arterials program, where [shortening] crossing distance and visibility at the corners would benefit more people more of the time."

The SFMTA plans traffic calming for arterial streets and around schools separately from the application-based local streets "track," which tends not to include areas, like the Tenderloin, with the highest injury rates in the city. Since the changes to the local track will make it more cost-effective, it will be able to implement roughly the same number of traffic calming measures using just $500,000 per year, Sorell said, freeing up $2 million for the arterial and school tracks.

"If you look at the map of the places where the most people are seriously hit and hurt by cars, and the map of where the SFMTA's traffic calming has gone," said Stampe, "they're nowhere near each other. It's really frustrating."

SFMTA staff plans to present proposals to improve the arterial and school tracks to the SFCTA Board in the coming months, said Sorell. The priority plan for the arterial track, which focuses on high-speed corridors, would be largely guided by police data, the Planning Department's WalkFirst report, and the SFMTA's developing Pedestrian Action Plan, intended to serve as a blueprint to meet the city's goal of cutting pedestrian injuries in half by 2021. Last week, the SF Department of Public Health published an online interactive map highlighting streets with the highest numbers of pedestrian injuries.

"We want to see a systematic approach to traffic calming on the city's most dangerous streets," said Stampe. "That's the 5 percent of our city's streets where people are hit and hurt the most."

"We absolutely need a program to address [traffic calming requests]," said Sorell, "but we also know that an application-based program doesn't necessarily reach every worst location. It reaches the worst locations where somebody has made the decision to apply."

Sorell said the proposed changes to the traffic calming program were based on successful models used in other cities. Stampe praised the simplicity of the application process for New York City's Neighborhood Slow Zone program, which is planning a round of 13 zones for this year.

"We're encouraged that SFMTA is moving forward on this," said Stampe. "We want to see a systematic approach to fix these streets by 2021. That's the goal the city has set out in the Mayor's Executive Directive and that's what we want to see in a Pedestrian Action Plan: fix five miles of streets per year."