At the latest city hearing on pedestrian safety, Jane Kim, supervisor of District 6, which sees more pedestrian injuries than any other, contrasted the typical reaction to vehicular violence with the typical reaction to gun violence.

"We should treat cars, in many ways, like a weapon. It has the same impact," said Kim, pointing out that at least one in five patients treated for traumatic injuries at SF hospitals are victims hit by drivers. "Even if intentional or not, when you are driving a car, you are driving a very dangerous weapon, and you can use it wisely, and use it safely, and not harm anyone, but you can really injure people severely and kill people."

Yet when a driver kills or maims someone, chances are slim they'll face any legal repercussions as long as they were sober and they didn't flee the scene. Why are cars, which injure two to three people every day and killed as many as 20 last year, treated so differently than other weapons?

Of the nine people known to have been killed in San Francisco traffic so far this year, only two drivers are known to have been charged. David Morales was charged with murder after killing 26-year old Francisco Guitierrez and car passenger Silvia Tun Cun, 29, in a car crash when fleeing police after a shooting on New Year's Day. Kieran Brewer is facing felony charges for killing Hanren Chang on her 17th birthday in a crosswalk while driving drunk on Sloat Boulevard.

Meanwhile, there's no indication of any legal consequences for the drivers who killed Sunnyside Elementary custodian Becky Lee in a crosswalk last Wednesday, retired teacher Tania Madfes in a crosswalk in West Portal in late March, Eileen Barrett in a crosswalk at Lake Merced in February, Diana Sullivan on her bike on King Street in February, or Melissa Kitson, killed when she was apparently leaving her SoMa office in January.

So this seems to be the takeaway: If you want to kill someone in San Francisco and get away with it, use a car. Just don't commit felonies or drink before you get behind the wheel.

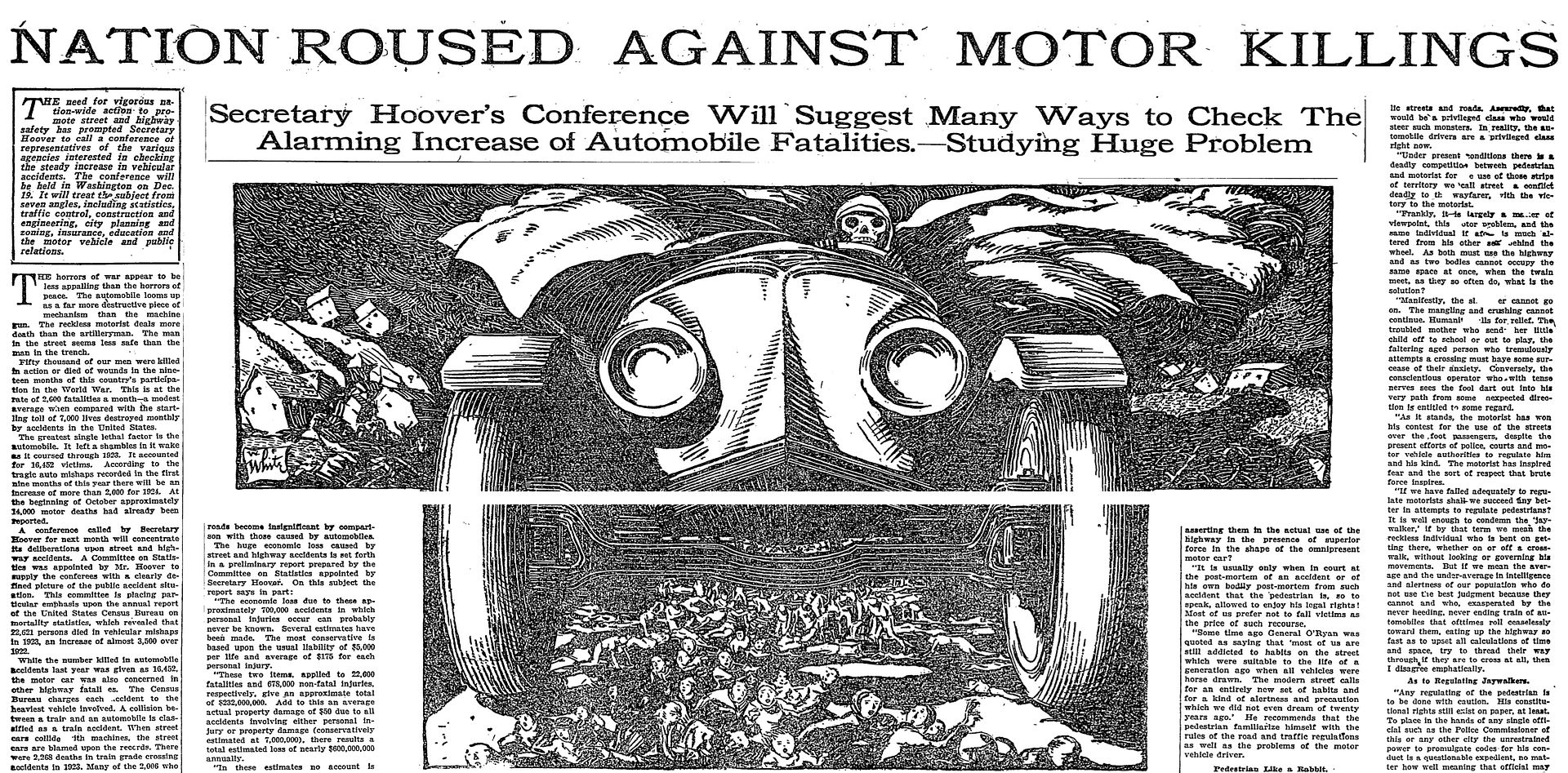

It wasn't always this way. Streets in American cities were once considered to be truly public places, where, for instance, children could play. When automobiles arrived in the early 20th Century, one of the huge social shocks was the huge number of child pedestrian fatalities. At the time, cars were mainly regarded as a menace by city residents.

As Peter Norton chronicles in his book Fighting Traffic, it took a sophisticated, large-scale PR campaign by car companies, automobile clubs, and other elements of what he calls "motordom" to shift public opinion toward acceptance of the car and car-oriented streets. By the 1930s, through lobbying and media campaigns, new concepts like "jaywalking" became entrenched, and American cities began imposing a new order on the streets.

The vast majority of street space was allocated to cars. Pedestrians were relegated to the margins, and laws were enacted mandating the use of pedestrian-specific rights of way like crosswalks. As responsibility for traffic injuries shifted away from motorists, pedestrians who were struck could be blamed as "reckless" when entering the roadway. That attitude still dominates today, unlike the notion of the car-as-weapon, which only recently seems to be regaining traction.

"You see real demonization of the car in the 20s that's been totally forgotten," Norton said in a recent edition of the podcast 99% Invisible. "Nobody remembers the memorials to the car, nobody remembers the monuments, nobody remembers the parades with Satan driving a Model T. Nobody remembers the cartoons, the editorial cartoons that routinely compared cars to the grim reaper, and Moloch, and Juggernaut, and all that."

Hear Norton tell the story, and see more images from the era on 99% Invisible's website. Here's the full podcast: