Urban planners, at least when it comes to bikeway design, are still trying to undo the damage caused by vehicular cyclists in the 1970s and 80s, explained Bill Schultheiss, a traffic engineer who specializes in bike design and a member of the Bicycle Technical Committee and the Pedestrian Task Force of the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD), with the Toole Design Group. "There was a fear that cyclists would no longer be able to ride in the streets and would be relegated to sidewalks," he added. "To this day, that has discouraged protected bike lanes in the [road engineering] guidance."

Schultheiss, part of a panel on protected bike lanes at SPUR Oakland this afternoon, said it also led to a culture of victim blaming. "When bikes are hit, we don’t want to accept it was bad roadway design," he said. "So whenever you read in the newspaper about a cyclist getting hit, you always see references to whether they were wearing a helmet, drunk, wearing dark clothes--putting all the onus for safety onto the cyclist."

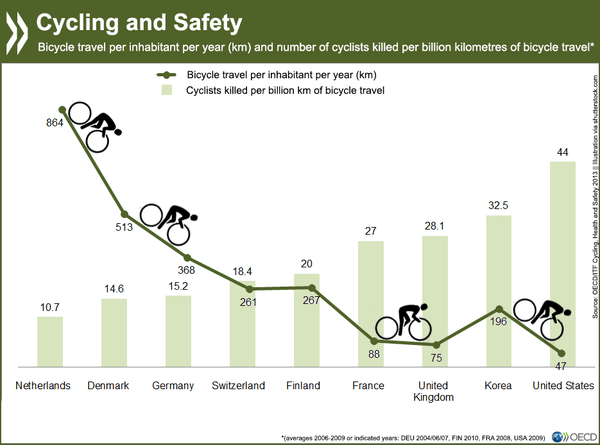

He talked about how countries that have the highest bike use, and the best safety records, also have very low helmet use. "Look at behaviors of people, look at moms and families, they’re not riding on streets with children on [paint-only] bike lanes in a high speed environment."

"In America we have very low rates of cycling but an outrageous number of people getting injured and killed," he said.

He showed a video of himself riding down a street in Seattle in a conventional American bike lane, positioned between parked cars and a lane of traffic stopped at a red light. As he rides along in the bike lane, he passes a truck. But when the light turns green, and the truck starts moving, he ends up approaching the intersection in the truck's blind spot. "Going through the intersection you shoot through a canyon [of cars and trucks]. I’m suddenly riding next to a dump truck." He explained that he had to be very wary, keeping a close eye on the truck's front wheel to make sure it was not going to turn right. Failure to notice if the wheel starts to turn, and failure to react quickly enough, can be the difference between life and death. "It's very unsettling; for someone who’s new to cycling it’s intimidating."

It's intimidating and dangerous. Schultheiss said that roads where people are afraid to cycle usually, albeit not universally, have the highest collision rates. And if we want women and families to ride, as they do in the Netherlands and other nations, we have to improve actual safety--not just perception, he said. "The strong healthy male is not the default bike rider anymore--we have to change who the design user is."

That, of course, means adapting European-style protected bike lanes and intersections. "We’ve muddied the waters for forty years telling people to 'take the lane' and that 'bikes are vehicles,'" he said. "On streets where the speed limit is more than 30 mph, where there are more than 6,000 cars a day, you have to protect cyclists."

But just saying protected bike lanes are the answer isn't all there is to it, he added--and some protected bike lanes are better than others. Fortunately, Dutch traffic engineers and others have decades of experience figuring this out. "There's lots of research ... Generally one-way bike lanes are safer than two-way when they’re protected, although protected bike lanes are always safer than unprotected."

He's also not a big fan of Danish-style mixing zones, the kind Bay Area residents are probably familiar with. This is where the protected bike lane ends at the intersection, and bikes are supposed to jostle for position with right-turning cars.

Cars are supposed to yield to bikes at these intersections, but they don't.

"The cyclist is in the blind spot," explained Schultheiss, who was skeptical that mixing zones were ever created with bicycle safety in mind. "This type of bikeway design is [meant] to maintain a higher level of service as a priority. It can work at slow speeds, but the aggressor is going to win. And the aggressor is the motorist."

The right answer, he said, is to do away with the mixing zone and maintain bike protection clear across the intersection. "You've got to change the intersection geometry to slow cars down, because drivers are used to turning fast. By the time the driver reaches the point where they [might] hit a cyclist or pedestrian, their speed should be nearly zero miles per hour."

Also presenting on the panel was Mike Sallaberry, Project Manager for SFMTA's Livable Streets division, who had some real-world prescriptions for getting better infrastructure installed. But first he had a confession. "I started out riding with the mentality of a vehicular cyclist, maybe out of necessity and out of survival in the city." But as part of Vision Zero and the city's efforts to make cycling safer in SoMa and elsewhere, the push now is to install protected bike lanes as quickly as possible. He showed photos of 7th and 8th streets, which, until recently, had four high-speed lanes where cyclists had to ride between fast-moving traffic and parked cars. "We put in a large buffered bike lane, but people were just driving down it and parking in it. It just wasn’t working out." Despite the dangerous conditions, there were still some 250 cyclists per peak hour on each of the streets. Sallaberry showed how all of that changed a few months ago when parking protected bike lanes were installed.

"7th street now has a seven-foot [parking-protected] lane and a buffer for people getting in and out of their cars. We set it up so the painted buffer could be replaced by a raised curb. Those projects were completed in ten months, but would have normally taken three to five years," he explained.

There were lots of reasons for this, notably the Mayor's Executive Directive, which required the unusually fast implementation. But Sallaberry said it also required some innovations that will be applied moving forward. For example, they installed bus-boarding islands differently. "Instead of digging into the base, we said: let’s just pour the concrete on top of the asphalt. So we were able to build islands at one-quarter the cost in one tenth of the time, for about $60,000. It took a weekend to build it."

He also recommends using a phased approach. He showed, for example, a picture of a temporary hotel loading zone. "We use khaki paint for a hotel drop off," he said. "That way we can paint it, reassure everyone that we can fix it later, and get the problems worked out before we make it into concrete." He also said they are altering their approach to outreach--instead of telling neighbors they would like to do a street improvement, they do outreach around safety improvements--which are not up for debate. Instead, the outreach addresses local concerns within the context of making the street safer. He added that this is another advantage of phasing in paint and other temporary measures first. "With an impermanence of design and intermediate design elements, you can use a light touch ... with paint you can reassure the public that you can tweak and modify it later."

Sallaberry also extolled SFMTA's first protected intersection at 9th and Division in SoMa and the "Better Market Street" plan, which will ban private automobiles (except taxis) and create protected bike lanes throughout downtown.

Last to speak was Ryan Russo, head of Oakland's newly formed Department of Transportation, and a veteran of New York City's DOT. Russo talked about the incredible pace at which New York built infrastructure under the Bloomberg Administration. He recalled how in 2007, the city started with one protected bike lane. "It was a point-eight mile experiment on 9th Avenue; we didn’t ask the fire department," he mentioned, referencing San Francisco's delays with protected bike lanes due to fire department objections.

New York continued to roll out more protected infrastructure in Brooklyn, in Queens, on 2nd Avenue in Manhattan. They're also continuing to innovate. "We stripe the bike lane through the intersection and do all the things the manuals say you shouldn’t do," he said, adding that New York is adding yellow flashing signals to remind motorists to yield before turning across bike and pedestrian crossings. Of course, as Streetsblog NYC notes, the 2nd Avenue bike lane, and others in the Big Apple, still have their share of issues.

Russo is hoping to speed up Oakland's efforts to install more protected bike lanes. Grand and Harrison, part of the Lakeside Green Streets Project, will be getting a Dutch-style protected intersection. Telegraph's protected lanes will be extended and improved. Fruitvale Avenue has ongoing improvements too. But one of the issues for Oakland and other cities is that the time frame for projects is so long--up to ten years--that updated design guidelines often overtake what's currently being planned and installed. That's what happened with Lake Merritt's relatively new striped but completely unprotected bike lane, which got a barrier--on the wrong side.

Russo said he is working on change orders to avoid repeating that mistake. Oakland is already showing an ability to become more nimble than it once was about fixing dangerous road conditions.

The bottom line, however, is that cities must cast off the notion that bikes should be treated like small automobiles, rather than vulnerable users. That's why on all but the calmest streets the bike lane should be next to the sidewalk and protected from traffic by a curb or similar barrier. That, of course, also means working with the disabled and making sure the bike space and pedestrian spaces are clearly defined. But if done right, that can make things safer for everyone, since the bike space creates an added buffer between pedestrians and speeding cars. "Pedestrians and cyclists are in the same family," said Sallaberry.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.