A ground-breaking experiment in St. Paul, Minn., shows a shocking pattern of dangerous and aggressive behavior towards pedestrians. But also how solvable the problem is given the right attention and policies.

For most of 2018, researcher Nichole Morris, director of the HumanFIRST Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, has been measuring driver yielding at crosswalks around St. Paul.

Morris and her team initially found yielding rates were dreadful: Only 32 percent of drivers stopped. But they were able to improve that number more than double that using "human factors psychology," which is focused on altering group behavior.

Streetsblog reached out to Morris by phone this week to hear more. Here's what she had to say (edited lightly for length):

So I heard about your experiment, from seeing the sign (above) on Twitter. Can you explain this project?

The original assignment was to study what the St. Paul Police Department was doing with high visibility enforcement and the community engagement campaign around a program that they're doing call the Stop for Me campaign. It's been ongoing for a few years now where a plainclothes police officer crosses a crosswalk and any drivers that have sufficient time to stop but doesn't will be fined.

Then they will have community members come out and cross the street with banners and are out there with signs saying, you know, "We Love Our Pedestrians" and things like that so that they really have a community engaged approach to encouraging drivers to look out for and stop for pedestrians.

So the Minnesota Department of Transportation wanted to measure how effective that high-visibility enforcement is. Nationally recognized researcher Ron Van Houten and I set out to measure how effective is the Stop for Me Campaign was but also to use some addition Human Factors Psychology tricks to enhance what they're already doing and use some additional engineering strategies.

Tricks?

We started measuring driver compliance to the crosswalk law back in the fall of 2017.

We picked 16 sites across St. Paul, which is a fairly sprawling city. These are two-lane, three-lane, four-lane and five-lane roadways. We crossed them 20 times, twice a week.

We used staged crossings, and the reason we do this — where we cross the street ourselves — is, one, to get sufficient data. Pedestrians are not always around when you would like them to be. Or sometimes a pedestrian will show up but they won't feel very comfortable stepping into the lane of traffic which is what you have to do to make drivers obligated to stop for you by law.

So we had to to do it ourselves where we sort of are walking, trying to look as causal. We stepped into the street, they have more than enough time to stop for us. And if they go through the crosswalk at that time, they've now violated the law.

Were they [stopping] less than 10 feet from the crosswalk, were they they 10 to 40 or were they greater than 40? That's really important because on multi-lane roadway, if they stopped really close to the crosswalk, now they're creating a sight trap for drivers in the next lane of travel. That can be a fatal situation for pedestrian who steps out into the next lane thinking all vehicles are going to stop — and a next vehicle could be flying down the next lane of travel and won't have time to brake at all. We want to encourage drivers to stop further back.

Last fall in 2017, we found that about three out of 10 drivers were stopping for us and the rest were not. So it was pretty poor compliance.

When we were taking our coders out to train them, Ron was saying, "We have to have a lot of these before we would even see what a passing event looked like." But we were seeing them sort of left and right. At the end of that fall data collection we found that about about one every every 10 crossing we were doing, about 11 percent, we saw a passing event. So one car stopped for us and the next car in the same direction of travel went right on by. Either in the next lane of travel or sometimes they cross on the right. Or sometimes in a really egregious situation they'll actually pass on the left, go into the other lane of traffic, they're so impatient to pass.

So that's illegal right?

Right. [Laughing.]

I think it's not actually illegal everywhere. It varies from state to state.

You're right. It's not illegal everywhere.

Even though it is really dangerous.

Right. It is really dangerous.

Really what's startling is the speed at which people do it. It's one thing to do that maneuver, but just to crawl past to make sure there's nothing you're missing. We see people just go through at full speed. In their mind, that car is turning left, and holding them up, and so they're going to fly around on the right. It doesn't dawn on them at all that there might be another reason why that car is stopped.

Was it scary for you doing these tests yourself?

Yes. Yes. Yes. [Laughing.] Yes.

Absolutely. I do these crossings, I have research staff doing it and I have undergrads doing it. I have to be very honest with anyone working on this study that we are risking our lives to do this work. Early on, I would have these panicky moments, where I would say to myself, "Is this too dangerous?"

What the big takeaway?

It's clear that some drivers just are not paying attention. And I don't even mean they're distracted, they're looking at their phones.

People are just not scanning the roadway looking for pedestrians. They're not looking for us and they don't see us.

There's other drivers that clearly see us, and some of them do this weird thing, they slow down so much we're almost certain they are going to stop and then they don't. It's baffling. We finally think we've figured it out. They're prepared to stop if we step out in front of them, but if we don't step out they're not going to stop.

I get a lot of feedback from community members who aren't very pleased because they want me to be chastising pedestrians more. They think pedestrians are the problem and pedestrians are jumping out into traffic. I almost feel like a lot of drivers are conditioning pedestrians to do that. They won't stop for you unless you step out in front of them.

A big part of it is just convincing people the problem is real and they should care about it. And to educate people about how critical it is not to pass a vehicle at a crosswalk and to stop farther back.

The police wave was just a warning. It was just an opportunity for police to pull over more than 1,000 drivers and give them a flyer and say this is why I pulled you over and this is why it's important not to do it.

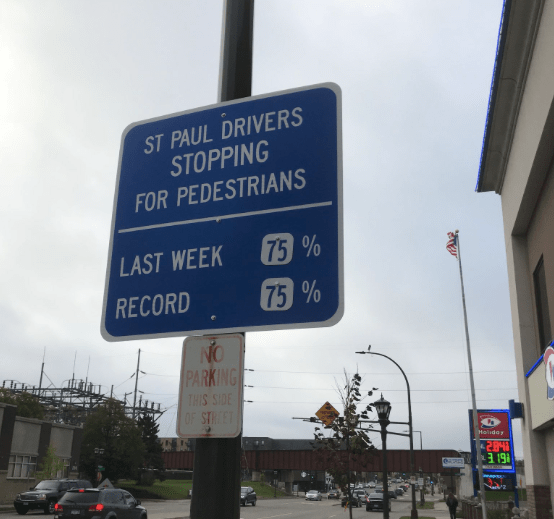

Then in June in 2018, that's when we did a second enforcement wave. That's when those feedback signs (pictured above) went up. That's what gets shared a lot on Twitter and social media. That's using a [human factors psychology] principle called social norming and it uses other principles like implied surveillance.

We put up these big signs that said "St. Paul Drivers stopping for pedestrians" and then it has a line that says "Last week" and there's a placeholder for percentage and "Record" with a placeholder for percentage. So social norming works really well when you can show people that the majority of their peers do a certain behavior that's a good behavior and to encourage people to be more like their peers. If you convince drivers that most people do stop for pedestrians, then they're going to feel more pressure. they want to be part of the pack.

The first number we posted was less than 50 percent. It was 44 percent, we weren't proud to put it up. The press started covering it like the signs we're designed to shame people. That was not the point. They were designed to motivate and inspire people.

(After the first week) we started getting excited because we could see the numbers were coming up at some of these sites.

The signs had been up for a few weeks and the local press just really didn't pick up on it right away. Then all the sudden, you know how it works, one agency covered it, and then the rest of them jumped on. Then we had this week of just massive press. And that was where we had a big jump.

The third wave of enforcement, which was in August, we put up simple R1-6 signs (pictured right). Those went up at our treatment sites and they were very effective. We started doing another wave of enforcement. Then we started seeing compliance in the 70s, which is just a dream compared to where we were last fall.

Then we did our fourth wave in October and we enhanced those in-street signs to "gateway treatments." A gateway treatment [see note below] is when you have that R1-6 sign on the center line and then when you have one in the outside lane. So you're driving through multiple signs on a gate.

That has been shown by Ron Van Houten in other cities to be a really effective treatment.

Were you guys be able to see any tangible safety improvements like a reduction in crashes?

I don't know yet. That's something I'm looking forward to trying to do. The number of fatal pedestrian crashes in St. Paul is low to begin with. I don't know if we'll have enough statistical power to reach any conclusions.

Is there much hope that much of this stuff you're discovering become more widespread and be implemented on the state and federal level? Like we never see the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration hammering this important lesson about not passing cars that are yielding to pedestrians.

We started with 11 percent of our crossings experienced a pass event. On average we're (now) down to 1 and 3 percent a week. So we have dramatically increased the number of unsafe pass events.

I got a lot of criticism from people in the community or in the engineering community that would say, "You're just going to make it worse because if you get more people to stop there's more opportunity for unsafe passes." We showed we could improve yielding and reduce unsafe passing. But we were really focused on it.

One thing that we did do, I was looking at the penalty for unsafe passing in Minnesota and it's the same as if you don't stop for pedestrians and you get caught it's like $181 fine. If a car is stopped for pedestrians and you pass that car, it's still $181.

The risk of those two behaviors is not the same.

We couldn't change that because it's a Minnesota state law, but the police department change its policy so that when they catch that behavior, they can check this box that says "endangering life or public property." If the box is checked, the driver cannot just pay the fine and move on; they have to appear in court. That's an extra added hurt to have to appear before a judge and be chastised for almost killing someone.

So that's something I'd like to see more cities emulate.

Thanks so much, Nichole. Fascinating research! We hope other cities will emulate it as well!

[Editor's note: The Gateway treatment is considered an "experimental treatment" under the Manual on Uniform Control Devices, an important engineering manual, which means adding them involves extra work for local agencies This is yet another example of the the influential National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices standing in the way of innovations that might improve pedestrian safety, even as pedestrian fatality rates soar.]