Note: Metropolitan Shuttle, a leader in bus shuttle rentals, regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog Los Angeles. Unless noted in the story, Metropolitan Shuttle is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

It's likely to cost around $300 million to build a bike path across the western span of the Bay Bridge, finally giving cyclists and pedestrians (and scooterists) a way to get between San Francisco and Oakland.

The price tag came up at last night's Bay Area Toll Authority-sponsored public meeting to get feedback on the proposed "San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge West Span Bicycle, Pedestrian and Maintenance Path" project. As previously reported, the idea is to add a bike lane off the side of the existing deck (more details are available on the Metropolitan Transportation Commission's web page on the project).

The projected cost seemed to get CBS's famously motor-centric Phil Matier upset. "That comes to about $100 million per mile...a boatload of money," he said in his report. He likens the high costs to the overruns of high-speed rail and the Transbay Terminal. He also implies the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition has an outsized influence on the decision to build such an expensive path.

But there's a reason the path is projected to cost so much.

The western span of the bridge is 58 feet wide. There are five lanes on the bridge's upper deck and another five on the lower--all of them accessible to cars, with cyclists and pedestrians banned.

When the bridge opened in 1936, there were six car-only lanes on the upper deck. The lower deck had three lanes for cars, trucks, and buses (one lane was reversible). There were also two train tracks.

In 1958, rail service ceased and the bridge was later modified to its current configuration, so private cars get use of all lanes of both decks.

The only reason the bike and pedestrian path will cost $300 million is because it is now politically infeasible to get any of that space back from cars. To make bike and ped space, we have to widen the bridge.

If Matier thinks costs are excessive, as his story more than implies, how about instead of widening the bridge, we discuss modifying it again to something akin to its earlier configuration. Maybe two lanes could be reserved for buses, as they were once reserved for trains. In fact, adding Bus Rapid Transit to Bay Area bridges was actually one of the winning proposals from MTC's Horizon's project.

Another lane could be converted into a protected, two-way bike path.

This would increase the capacity of the bridge, smooth commutes for tens of thousands of bus riders, and finally give cyclists an option to travel between San Francisco and the East Bay. It would also reduce the need for cyclists to ride BART, opening up more space on our overcrowded trains.

And all for the cost of a new ramp for bikes and about 10,000 feet of concrete barrier to keep cyclists safe from collisions.

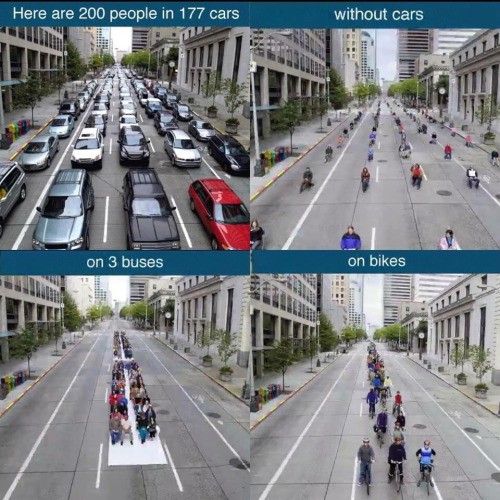

Of course, that simple, inexpensive solution will never happen--because we start every conversation with the assumption that fair distribution of road resources means keeping all space available for the most inefficient means of transportation, also known as private automobiles.

So don't blame bike advocates for the costs of a bike and pedestrian path; sorry Matier and other motorists, but that's on you.