Note: Metropolitan Shuttle, a leader in bus shuttle rentals, regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog Los Angeles. Unless noted in the story, Metropolitan Shuttle is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The iconic Hovenring bicycle bridge in Eindhoven in the Netherlands is now recognized the world over (at least by bicycle enthusiasts and planners). But how does innovative bridge and other bicycle infrastructure get constructed?

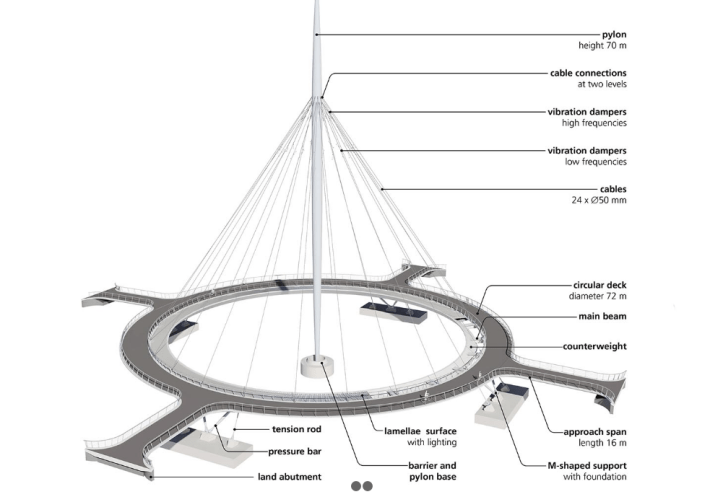

Traffic planners in the Netherlands identified a problem back in 2008--at the intersection of Heerbaan and the Meerenakkerweg roads. "Before the bridge, it was shared by all modes and it was very congested," said Adriaan Kok of ipv Delft, which came up with the design, at a panel Monday evening at SPUR's Oakland location. It was no longer safe and comfortable for bikes and the traffic was only going to get worse. "And more developments were planned." So they set out to completely separate bike and motor traffic.

Building an iconic bike bridge seems like a good idea for continuing to attract the tech industry. "People who like to work high tech also like to ride bikes," added Kok.

Tunneling the roads or bike path under the intersection wasn't an option because of the high water levels. On the other hand, they also couldn't go too high. "We had to take into account the nearby airport... and the danger of a plane crashing." They also wanted a bridge that would reflect the high-tech industry of the area, home base to Phillips and a Tesla plant.

It's said that constraints boost creativity and this certainly seems to be the case with the Hovenring. How to balance the height and depth restrictions? "We lowered the new car crossing, by 1.5 meters to just above groundwater level," said Kok. That also allowed them to minimize the gradient cyclists would have to climb to reach the bridge deck.

In most cases, bridges over roads are constructed to withstand an impact with the top of a truck if it's higher than clearances permit. That usually means building a very heavy deck, which brings up the weight--and costs--of all aspects of the project. Instead, they built the bridge just strong enough to support maintenance vehicles.

They suspended road signs over the lanes on heavy concrete supports. That way an oversized truck will crash into the sign well before it reaches the bridge. "By building signs to filter oversized vehicles, we economized a million euros." They also used prefabbed parts and assembled the bridge from basic segments that repeat throughout the structure. They built the deck wide enough so two pairs of cyclists can pass each other. And, as seen above, there is a counterweight ring so there's no need to have suspension cables on both sides of the ring. Kok said the cost was 6.3 million euros. It opened in 2012.

Meanwhile, closer to home, the Bay Trail is also getting a dose of architectural innovation. And that's important because iconic bridges and inviting bike paths get more people out of their cars.

"Since I was ten years old the number of people on the planet has doubled from 3.8 to 7.7 billion. While our population has been doubling, our burning of oil and gas has almost tripled," said Steven Grover, architect and another of the panelists. Unfortunately, in the U.S., most freeway overpasses are designed in a utilitarian, hard-concrete way. "In the U.S. we established a very persistent architecture for transportation based on functionality. It's focused on making it possible to walk somewhere, but with no notion of designing things to make it desirable to walk or bike."

That has resulted in bike and walking paths that, when they exist at all, have no sense of place. Grover's firm tries to reverse that. "We strive to make landmarks appropriate to the local context," he said, citing a design for Adobe Creek in Palo Alto and the Berkeley Bike Bridge over I-80.

There's another purpose--it catches the eyes of millions of motorists. "Make some appropriate visual landmarks so motorists think of using them."

Grover is also working on designs for a bridge to connect the Bay Trail to Lake Merritt.

Speaking of innovation, Grover is best-known for developing the BikeLink system, which he invented. There are now over 300 electronic lockers at transit stops in the Bay Area. Because the lockers are shared and unlocked electronically, instead of needing a traditional key, "The system serves ten times as many people as the systems it replaced."

Last to present at the panel was Brytanee Brown of Oakland's Department of Transportation and Baybe Champ of the Scraper Bike Team. They talked about what can be accomplished with good community outreach and some paint. Brown said she is inspired by Ethiopia, where streets are shared by cars, taxis, bikes, pedestrians, and even cows and goats. "A lot of my design influence comes from this," she said. "How can many users access the street in a way that’s flexible and safe?"

They're also operating from restricted budgets, so paint and plastic posts, combined with imagination, are their tools. "They’re a little more low cost," she said. "That is our challenge--and this is where the innovation stems from."

Working hand-in-glove with Champ's Scraper Bike Team, they were able to come up with a center-running solution for 90th Avenue, a high-injury corridor in East Oakland. "Currently, there’s some unmarked crosswalks... it's not technically a safe place to bike, with no bike lane and pavement quality that isn’t great."

"That’s my neighborhood. That’s where I was born and raised," added Champ. "The Scraper Bike Team is known for riding in the middle of the street and just taking over, because historically there haven’t been any bike lanes, and I want to be smack dab in your face so you can see me," he said.

After outreach in the community, that philosophy was used to reject traditional side-running bike lanes in favor of one in the middle, as seen in the rendering. "With bright vibrant colors... I selected orange, because what’s brighter than orange aside [from] yellow?" But yellow means caution, and he wanted it to feel inviting rather than warning people off.

Longer term, when the city has time and money to build a more permanent configuration, a new configuration, perhaps with conventional side-running raised cycle tracks, might be in order. But for now, says Champ, "Center running was the best fit for us." He added that when people saw the design, they loved it. "Now it’s becoming a realistic, tangible vision."

And what about new forms of mobility, such as scooters? How will they fit into this paradigm of creating architecturally inviting infrastructure? Grover said Caltrans' Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee is discussing "...separation by speed rather than the type of wheels... maybe in the future we won’t just talk about peds and bicycles, we’ll talk about how fast people are going."

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.