The tragic deaths on San Francisco streets keep increasing. San Francisco’s Vision Zero is not making progress. The city is forming an action plan, but it’s not aggressive enough: how about day-lighting every single intersection? Congestion pricing may reduce overall traffic, resulting in fewer death agents.

However, the city has no solid plan for the real killer: speed.

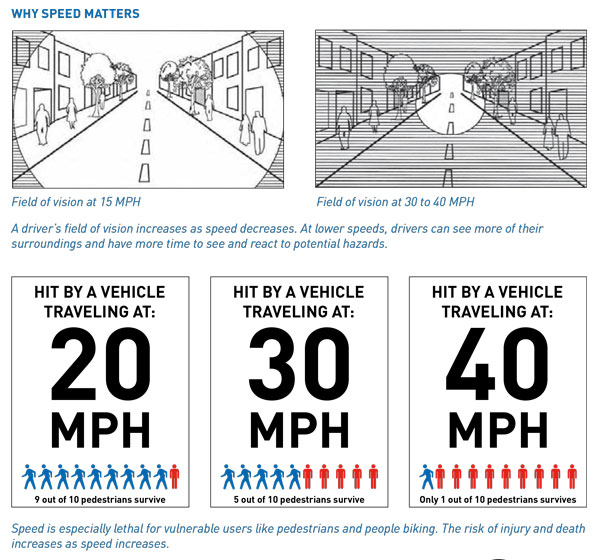

High speed, regardless of limit, is a factor in every traffic fatality. It leaves little time for drivers to become aware and react (avoid). It takes longer for braking to take effect (minimize). And finally, it inflicts higher blunt force trauma on victims (mitigate). That is why less than 7 percent of collisions at 20 mph are deadly, while 45 percent of collisions at 40 mph kill.

There is usually another factor in traffic fatalities: most often a driver error, such as ignoring the pedestrian right of way, running a red light, glare, lack of visibility, inattentiveness, negligence, DUI, etc. We can and should try to minimize such errors by improving visibility (day-lighting) and enforcing traffic violations (e.g. using red light cameras) like the action plan proposes. But as long as speeds are high, a single driver error will remain fatal. It is a single point of failure, therefore high-speed streets are deadly by design.

Today, speed limits in California are set based on the 85th percentile rule: out of 100 drivers observed, the limit is set to the speed of the 15th fastest driver. That means that wide streets where traffic is unimpeded result in higher speeds, and higher speed limits. There are efforts to change that, but failure to change state law has been used as a crutch for San Francisco to do nothing. Furthermore, speed limits without corresponding design and enforcement changes may or may not be effective but will provide a false sense of security. In deadly situations, what matters is not the speed limit, but the actual driver speed, which is typically higher than the limit.

To address this challenge, San Francisco must actually prevent speeds higher than 20 mph city-wide, as follows:

- Measure the speed percentile distribution on every single block.

- Set a goal of 20 mph 99th percentile speed everywhere, in particular at intersections, crosswalks or streets where bike lanes are present. The posted speed limit may itself be lower (or higher, if the 85th percentile rule survives).

- Track progress towards the goal, to keep SFMTA and City Hall accountable. The same way SFMTA tracks Muni on-time performance, it should track its progress towards the 20 mph goal.

- Prioritize changes to design and enforcement on streets where the goal is not being met.

The city should implement any and all approaches to achieve the speed reduction, such as:

- Traffic calming, such as lane reduction, lane narrowing, speed bumps, raised crosswalks, optical treatments.

- Enforcement, such as automated speed enforcement (currently illegal in California). The absence of automated enforcement, however, should not prevent the city from doing everything else.

- Speed limit reduction, which can be effective on its own, or when coupled with enforcement and design changes.

- Signal timing, to reduce incentives to speed.

- Roundabouts to reduce speeds at intersections and improve turn visibility.

The city should rapidly pilot different approaches on different streets of the high injury network to see which approaches achieve the desired speed reduction.

Some may ask, how about transit? Average transit speed today is 8 mph. The reason for that is not the speed limit, but traffic interference. The way to improve transit is via transit-only lanes, signal priority, congestion pricing, and grade separation. The San Francisco Transit Riders ambitious 30x30 campaign is fully compatible with speeds under 20 mph: the Geary lines (6.4 miles) need to only average 12.8 mph to take riders end-to-end in 30 minutes.

Some may ask, how about arterials, such as Oak and Fell? First, we should make safety the default and speed optional, rather than the other way around. To institute higher speeds, SFMTA must identify and propose alternative solutions that result in zero deaths.

Until then, 20 is plenty.

Mario Tanev is a long-time member of Walk SF, SF Bicycle Coalition and SF Transit Riders, where he led its first successful campaign to institute Muni All-Door Boarding.