Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

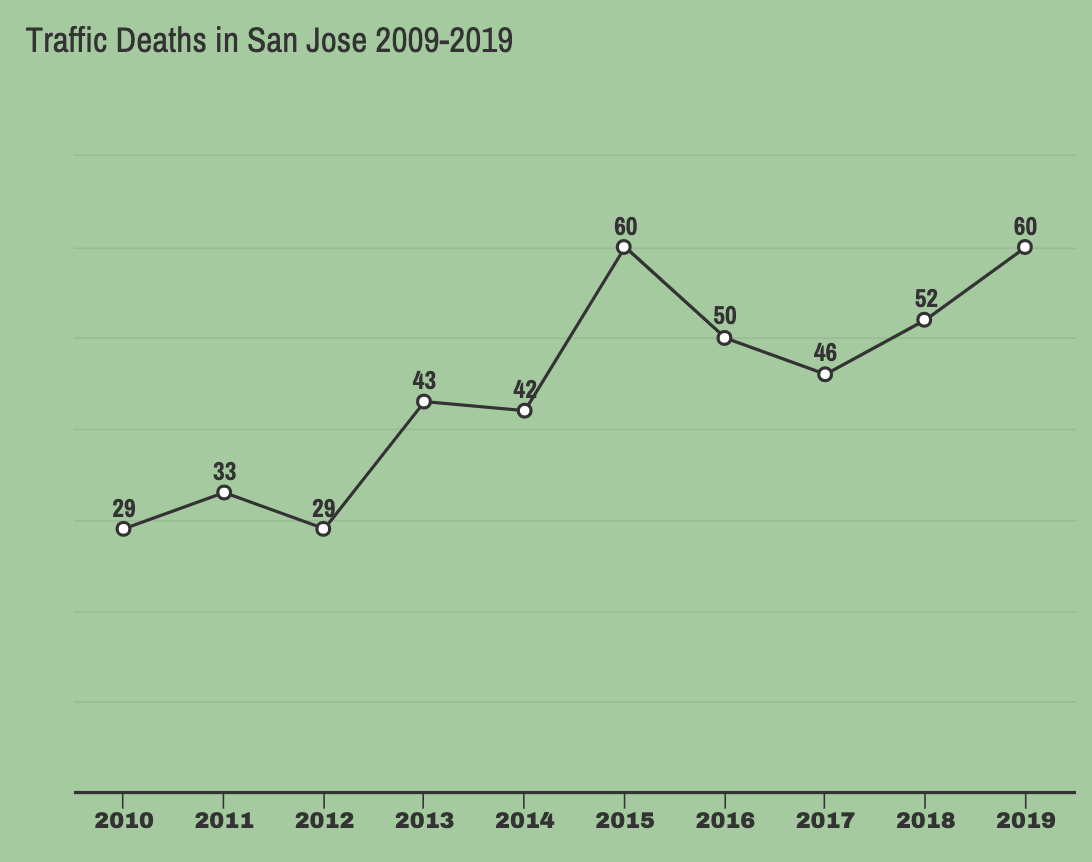

The City of San Jose adopted a "Vision Zero" policy in 2015, meaning that the city's decisions on transportation projects and enforcement would be guided by a goal of reducing traffic fatalities to zero. However, since adopting that policy, fatalities have been high, with both 2015 and 2019 tying for the years with the most fatalities in city history. The end of 2019 was particularly brutal, with headlines in the local newspapers blaring: "2019 the deadliest year for San Jose pedestrians in decades" and "Quest to Make San Jose Streets Safer Crashes into Worsening Pedestrian, Cyclist Injury Stats."

Mintz-Roth and the San Jose Department of Transportation (SJDOT) have been preparing a plan to create safer environments along 15 of 17 identified"priority safety corridors," where 43 percent of fatalities and 33 percent of severe injuries are caused by unsafe driving. They will present this plan to the City Council for funding on February 11, following a committee hearing on February 3. SJDOT will ask for $20 million dollars to improve safety along those corridors.

"We're focusing on 56 miles on 15 high priority safety corridors under our jurisdiction...Our goal is to build out 11 miles per year for the next five years," Mintz-Roth explains. There are two other "priority safety corridors" that are in the control of Santa Clara County and will require more coordination before improvements can continue.

The city will employ a quick-build strategy to attack these streets. This means that paint and plastic bollards will be installed quickly, to be replaced by permanent concrete barriers later.

Advocates have complained that the plastic bollards are not enough protection as the city grows more dangerous. In the story "Quest to Make San Jose Streets Safer Crashes into Worsening Pedestrian, Cyclist Injury Stats," Brandon Alvarado, a member of the city's Bicycle Advisory Committee, excoriates the city for not providing stronger barriers to protect bicyclists.

However, the city claims its goal is to replace these less-expensive options over time once there has been "proof of concept" that the new configuration is working. San Jose has had some success with this strategy on San Fernando Boulevard with its plastic bollard, parking protected bikeway.

"San Fernando is our major east-west bike corridor through downtown and it has been upgraded a couple of times. It was included in our better bikeways project in 2018. We added plastic bollards and transit boarding islands. After the proof of concept, we got a $13 million Active Transportation Program grant that will go to hardscaping that corridor," explains Colin Heyne, also with SJDOT.

As with most Vision Zero programs, the focus of efforts will be on reducing speed. According to reports by the San Jose Police Department, speed is the most common factor in fatal crashes in the city and that 94 percent of the 70 miles of high priority safety corridors (including the ones controlled by the county) have posted speeds over 30 mph. The likelihood of a pedestrian hit resulting in fatality is over 50 percent at speeds that high.

And the number of pedestrian deaths is at epidemic levels. Just last year, 29 people were killed in crashes while walking in San Jose. For comparison purposes, 29 is the total number of total traffic fatalities in the City of San Francisco over the same time period. Because of state laws that make it difficult to reduce speed limits, the notorious 85th percentile law, the city is not looking at changing posted limits along these corridors. Instead, it will use road diets, better bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and traffic enforcement to reduce speeds before looking at changing the posted limits.

"We are trying to re-engineer a transportation network that was really built out in the 50s 60s and 70's," concludes Heyne. "We're dealing with a transportation network that was built for cars."

Enforcing traffic laws has been difficult. In 2012, the San Jose Police Department had 45 officers. The department hemorrhaged members following a ballot initiative that changed the city's pension plans, and only recently has the department begun to recruit new members for its traffic division. In 2018, that number declined to just 5 officers. But SJPD brought that back to ten traffic enforcement in 2019.

Other portions of the city's plan include creation of a Vision Zero Task Force, putting more resources into education around traffic safety issues and creating tools to better analyze crash data and help the city prioritize how to spend its transportation resources.

"The biggest problem with implementing Vision Zero in San Jose in the past has been funding," explains Nikita Sinha, with California Walks. "The fact that this plan, especially around quick-build infrastructure, has layed out what the funding needs are is a step in the right direction."

But that doesn't mean that advocates believe the city's plan is enough to stem the tide of rising deaths on its own.

Sinha recommends the city shorten its timeline for the quick-build plan to address the most dangerous streets in a couple of years, not half a decade. She also wants the city to start figuring out how to fund the concrete replacements that will be needed after quick builds are completed. In short, the short-term planning needs to be implemented faster and the long-term planning needs to be happening at the same time.

"This plan goes so much further than previous plans," Sinha concludes. "I'm really hopeful about it, but I'm not willing to accept it as is."