Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The hills of San Francisco are no longer a reason not to bike, said Dirk Janssen, Consul General of the Netherlands, during a presentation Monday on how to apply Dutch expertise on cycling infrastructure. The presentation was hosted by the Dutch Cycling Embassy, an agency that teaches best-practices for sustainable mobility. "Electric bikes completely nullify the effect" of the Bay Area's topography, added Janssen, since the electric motor assist allows even novice cyclists to rocket up hills.

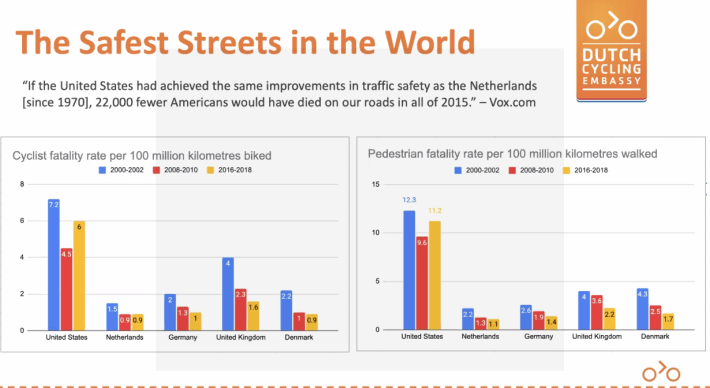

The seminar is part of an effort by the Netherlands to export their expertise on achieving one of the safest and most sustainable transportation systems in the world--built around excellent transit, good urban planning, and top-notch bicycle infrastructure. As the chart below shows, the Dutch have achieved 'Vision Zero,' the goal of zero or near-zero fatal crashes on city streets:

The infrastructure and planning that today makes Dutch safety and mobility standards so impressive were hard-fought. "The Netherlands was not born with this infra in place," explained the Cycling Embassy's Chris Bruntlett. "In the early 1970s, a safety crisis was killing 3,000 adults and 400 children a year in the Netherlands. In 1973, there was the OPEC oil crisis where for six months there were severe gas shortages."

Those two facts motivated the people of the Netherlands to rebel against freeway construction and road widening, which was increasing automobile use and killing their children. They started removing freeways, building bike infrastructure, and toiling to figure out how to build an integrated and safe network of bike lanes, transit, and pedestrianized cities. It was a tough learning experience. "We made mistakes. It was a process of 20 years before they came across design principles and realized the best way to build a bike lane," said Bruntlett.

"But we made all the mistakes so your city doesn’t have to," he added.

And that's the core mission of the Dutch Cycling Embassy: to help cities around the world avoid the mistakes that hurt and killed so many Dutch people decades ago.

Meanwhile, the presenters stressed that building walkable, bikeable cities isn't only about bike lanes. They have to be part of a system of transport, where urban design and bike lanes facilitate trips to fast, frequent trains, and visa versa. "They are all pieces... all bricks of the same building. A cycle lane is part of a total regional strategy," said Bas Govers, a traffic planner with a Dutch consultancy and another of the speakers. He spoke about the importance of using bike lanes to increase the catchment of transit hubs. If cities are planned correctly, there should be walkable plazas and protected, high-quality bike lanes radiating around medium to large railway hubs to help people travel to and from stations. "All these modes work together in one system."

That also means having excellent, secure bike parking around stations and, when appropriate, bike cars on trains. This also makes transit more efficient, since stations can be spaced farther apart, which allows trains to operate faster and decreases average door-to-door travel time.

With the Netherlands as a guide, it's clear that the geography and current layout of the Bay Area already has the important bits in place. Derek Taylor, another consultant who presented at the meeting, pointed out that the distances between job centers and the layout of BART and Caltrain aren't all that dissimilar from the western Netherlands. "51 percent of the jobs are located within the catchment zones" of Caltrain and BART he said. But with bike infrastructure lacking and the transit system uncoordinated and underfunded, "69 percent still commute by car," even to and from areas near Caltrain and BART stations."

That can improve if planners, politicians, and advocates put in the time and energy and learn from the Dutch about how to plan around those transit hubs. As one minister put it at a conference shortly before the COVID crisis began, "we need more bicycles, public transport, and brains."

Meanwhile, the COVID crisis has forced cities to rethink how they use their streets at a much faster rate. "Everywhere around the world cities are embracing cycling," said Janssen. "I love to cycle or walk on the streets now closed to through traffic, such as the Great Highway, Lake Street, Cabrillo... I hope they can stay like this after COVID is over."

The Dutch Cycling Embassy has a series of videos, manuals, and books on how to make more bike and transit-friendly cities. And make sure to check out Chris Bruntlett's book Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blue Print for Urban Vitality.