A good bike boulevard is apparently like pornography — you know it when you see it.

There’s no one definition for the “bike boulevards” that Mayor de Blasio announced in a potential bombshell in his State of the City address on Thursday night — and, indeed, Hizzoner declined to provide his own definition in his Friday morning press conference, preferring to delegate his proposal to the experts (the Department of Transportation declined to comment).

“The bike boulevards, are, I call them super bike friendly,” the mayor said. “They have a variety of treatments that encourage bicycle use and discourage cars. And the vision is to connect areas that need — you know where you have different bike lanes that need connections between them to provide that. So we’ll be having a lot more to say in the coming weeks as we unveil details. … But this is the kind of thing that will make it easier to be a bicyclist in this city — and safer.”

Well, it certainly can make streets safer, if done right. But there is no clear definition of bike boulevard. Mayor de Blasio’s apparent idea — shared space with “treatments” to slow down drivers — probably won’t satisfy Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, who earlier this year, told Streetsblog that he wants full fledged “bicycle superhighways” (but the Beep hasn’t released any designs yet either for his proposal, which calls for converting space under highways for cyclists).

“It has become apparent in the last 24 hours that the term ‘bike boulevard’ is very new for people in New York City,” said Brooklyn-based urban planner Mike Lydon of Street Plans.

Lydon said that several terms are used for bike boulevards, including “neighborhood greenways” or, if you’re a Briton, “low-traffic neighborhoods.” But best practices exist no matter what you call them:

- Reducing speeds through traffic calming treatments such as curb extensions, narrowed lanes and/or chicanes.

- Reducing car volumes, which can be accomplished by making thru traffic unpleasant or difficult for drivers (perhaps by using diverters every few blocks, or changing the direction of streets).

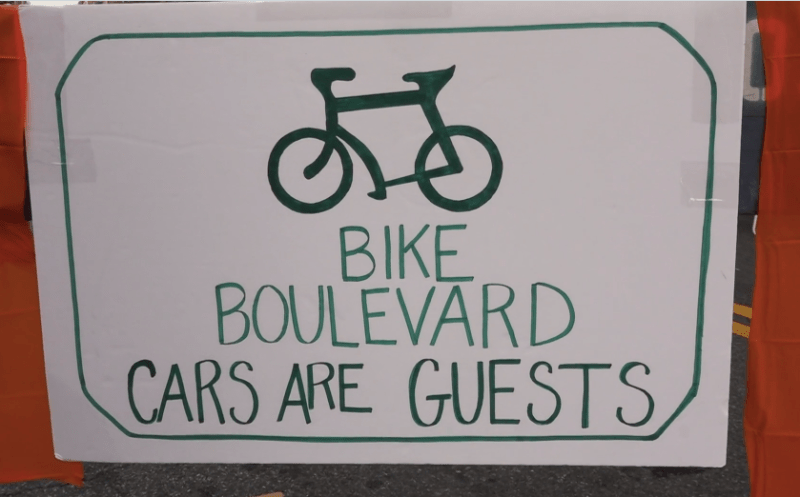

- branding the route — with clear wayfinding signs — so that people know that there is, indeed, a neighborhood greenway network.

“It’s an exciting announcement [because] when they work well, they offer quieter, alternative routes where traffic volumes become so low that people of all ages feel like they can walk, run, bike, socialize in the street,” Lydon said. “But the effectiveness will certainly be in the details of the program.” (Enjoy a slideshow of some of Lydon’s ideas for bike boulevards below.)

The National Association of City Transportation Officials — we call it NACTO — also has put out a guide for cities hoping to keep cyclists safe with bike boulevards. NACTO is advocating for such roadways to meet an “All Ages & Abilities” criteria so that bicycling is not merely a practice of recreational weekend warriors or road-hardened commuters, but something that everyone can do. The key reducing the number and speed of cars.

A shared street meets the organization’s criteria “when motor vehicle volumes and speeds are so low that most people bicycling have few, if any, interactions with passing motor vehicles,” the group says in its urban bikeway design guide.

That’s no small point because NACTO and Lydon’s designs coalesce around one major concept: Designing streets so that drivers slow down without the need for police or other law enforcement involvement. Groups such as Transportation Alternatives have long been demanding safe streets through design, rather than enforcement.

“We recommend reallocating significant portions of the NYPD’s budget to the Department of Transportation to, among other things, increase investments in street design and automated enforcement to create ‘self-enforcing’ streets,” TransAlt wrote in a white paper last year [PDF]. “This is a more effective way to make streets safe” than enforcement.”

Tuscon, Ariz. is seen as a leader in bike boulevards. The city has identified 193 miles of future bicycle boulevards along 64 corridors as part of a bike boulevard master plan adopted in 2017. (By comparison, New York City’s DOT mentions bike boulevards just once in its 2019 “Green Wave” plan, merely saying that such a configuration would “prioritize cyclists and limit vehicles on appropriate streets” — none of which were publicly announced.)

Paris (the one in France) and Somerville, Mass., where bike boulevards are called “neighborways,” are also considered leaders in the movement.

“The ones that work the best connect to major destinations and it’s important to limit the volume of cars, which will use every space you give them, by changing the direction of the street,” said Tom Lamar, the chairman of the Somerville Bicycle Advisory Committee. The city started creating bike boulevards in 2015.

One thing is for certain regarding Mayor de Blasio’s announcement: the term “bike boulevard” only truly got on the radar screen thanks to cycling advocates in town.

The civic groups City Rise and Streetopia UWS have done more to promote the notion of bike boulevards this year than any other activists [full disclosure: both groups are part of Open Plans, which publishes Streetsblog]. The City Rise launch last year included a call for bike boulevards, plus a video on the topic, and Streetopia did a demonstration of a bike boulevard at its West End Avenue Walks event in mid-November — all of which resulted in a Streetsblog article on the subject in November when the mayor’s State of the City address was taking shape.

The bottom line, of course, is how serious de Blasio is about the proposal and how intensely DOT carries it out in the last year of this mayor’s term. And, as Justice Potter Stewart famously quipped, we’ll only know that when we see it.