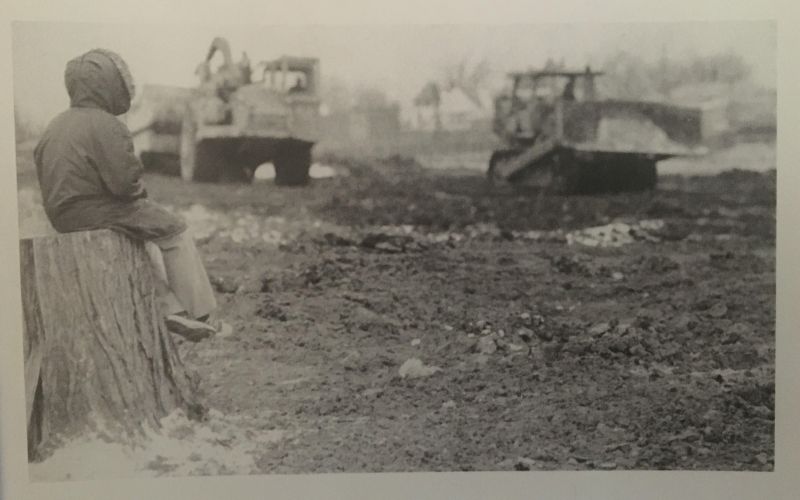

At the height of the urban renewal era, state and local governments across the country strategically routed highway projects through the heart of Black neighborhoods — displacing residents, destroying businesses, and shattering communities. Now, advocates from St. Paul, Minn., are hoping to restore some of what was ripped away by building a land bridge over a troubled roadway — and to provide an unconventional model for other communities.

After more than five years of organizing and a decade of dreaming, advocates from the nonprofit Reconnect Rondo are seeking $6.2 million from Minnesota to reconnect the historically Black Rondo neighborhood, which was almost completely razed in order to make way for Interstate 94 between 1956 and 1968. But unlike many of the highway removal proposals that have been applauded by urbanists, the project would leave the interstate intact, and install a massive, roughly 16 acre of cap that would become Minnesota's first "African American cultural enterprise district."

The land bridge won't be as large as the section of Rondo that the highway destroyed, a vibrant neighborhood once the backbone of the Twin Cities' Black community. Still, advocates think it could create a strong foundation for Black Minnesotans to thrive — and a blueprint for how other cities could use transportation space to aid the fight for restorative justice.

"I know first-hand what it was like when people were able to walk along Old Rondo Avenue, and I know the depression we felt when it was lost," said Reconnect Rondo Chairman Marvin Anderson, whose family was displaced from the neighborhood. "People still feel that today. When they took away our neighborhoods, they took away our ability to dream. And that's not just in Rondo; that happened to hundreds of other communities across the country."

'We've been banging on the door long before George Floyd'

Now 81, Anderson has spent most of his life telling the story of his lost neighborhood and seeking justice for its residents. Since 1982, he's hosted an annual festival in order to highlight the traumatic history of the highway and to honor the legacy of the region, which was once home to three Black newspapers, the St. Paul chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and 80 percent of the city's Black population. The state tore down more than 300 predominantly Black-owned businesses and 700 family homes in order to clear space for I-94, despite the existence of an alternative route along an abandoned railroad track nearby.

Anderson and his allies' efforts to keep the memory of Rondo alive led to a formal apology from the state transportation department and the city of St. Paul in 2015 , and the establishment of a commemorative plaza the following year. But it wasn't until the death of George Floyd last summer at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chavin that Anderson's most ambitious dream gained traction: a bridge, dedicated to the Black community, that would restore land lost to the highway.

"We’ve been banging on the door long before George Floyd," Anderson said. "It just made people on the other side of the door open it up and listen to us."

The idea of a land bridge across I-94 dates at least to 2009, but the concept is older; Seattle famously built a five-acre brutalist sculpture park atop a freeway cap in 1976, and similar projects followed in Boston, Dallas, St. Louis, and many others. But the Rondo project is unique for its size — it would span about four city blocks — and its focus on using land as a tool of restorative justice for the Black community, rather than its one-size-fits-all community benefits.

"This project has the potential to show people what holistic restoration for the Black St. Paul community looks like," said Keith Baker, executive director of Reconnect Rondo. "Not just 'we should build more affordable housing,' but also, 'we must address food scarcity, we need jobs that people can walk and bike to, we need to address impact of climate change on Black neighborhoods.'...[The death of George Floyd] was a reminder of how important it is to actually invest in communities of color, rather than simply monitoring those communities and putting them in boxes."

'It's hard to turn a cruise ship around'

Bringing the Rondo land bridge to life won't be easy.

White transportation officials, including Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, understand the potential of antiracist infrastructure projects, but the funds for such projects are still scarce. The Senate has yet to approve a $10 billion pilot program that would give predominantly low-income and BIPOC communities like Rondo the money for community engagement around highway removals. Moreover, it's not clear whether the Rondo land-bridge initiative would qualify for such funds, because it wouldn't remove I-94.

Baker says that he's not opposed to filling in the highway, but it's probably not realistic given I-94's status as Minnesota's most-used freeway, carrying more than 150,000 cars a day.

"To just decide to fill it would require first fully appreciating the impacts on the Black community itself," Baker adds. "The community does get resources through this incredibly important vein."

But local green transportation advocates stress that tout the land bridge is far from a half measure, because it would provide low-stress pathways for active commuters, as well as for advanced pollution-capture measures that would ameliorate local smog.

And advocates say it's far better than the alternative that the Department of Transportation is pushing: a highway-expansion project, "Rethinking I-94," which effectively would add 28 miles of carpool lanes to the aging highway.

The St. Paul City Council has called on MnDOT to strike the added lanes from its plans to repair the interstate. But advocates worry that structural barriers n Minnesota law will mean the expansion will win out over forward-thinking models like the land bridge. regardless of what the locals want.

Like most states, Minnesota has restricted the DOT from spending its fuel-tax revenues on anything but highways since the 1930s. That means Reconnect Rondo might need to raise much of the project's estimated $458 million total construction costs from a combination of government and private philanthropic sources — unless the state reforms its underlying laws.

"Minnesota needs to do what the federal government did in 1991 with the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act and 'flex' a portion of state gas taxes for non-automotive projects," said Andy Singer, co-chairman of the Saint Paul Bicycle Coalition, which supports the Rondo project. "Only then will we see an end to new road construction and funding for projects like Reconnect Rondo's land bridge...Land bridges are expensive but, particularly in cities with high real-estate values, they are a way of reclaiming taxable property from highways, short of removing the highways entirely."

For now, Reconnect Rondo is doing its best to get the DOT to provide the $6.2 million they need for the pre-planning stages of the project — even as it recognizes that the project is an odd fit for an agency more accustomed to laying pavement than blazing trails in restorative justice.

"It’s hard to turn a cruise ship around," said Anderson. "MnDOT is a partner in this development, but we’re both learning how to dance together. Our dance steps aren’t quite as smooth as we want them to be, but we could be on opposite ends of the dance hall. The fact that they’ve agreed to dance at all is good."

Baker, a veteran of MnDOT himself, couldn't agree more.

"It is quite a dance," he says. "Aside from the dynamics of the institution itself, you also have the MEPA [Minnesota Environmental Protection Act] and NEPA [ National Environmental Policy Act] processes layered on top...But at the end of the day, we're on a marathon, and we can't let MnDOT set the pace. "

This is what restorative justice looks like

Many details of the Rondo land bridge still need to be ironed out, although the Reconnect Rondo team says that's by design.

Baker and Anderson say it's essential that the process of planning the land bridge deliberately avoid the top-down strategies that characterized the original highway project (and that also dogged a proposed light-rail extension in the neighborhood.) But the team has already committed to examining a full slate of policies to prevent rapid gentrification, avoid displacing existing residents, and ensure that the descendants of the original neighborhood have their wealth and prosperity restored.

Expanding the Rondo community land trust, investing in affordable housing for elders who grew up in the Rondo neighborhood, and investing in small-business development for Black Minnesotans are all on the table, they say — and they expect to glean more ideas from residents themselves.

Until they have the money they need to begin, they're focusing on the big picture.

"We want [Black residents in St. Paul] to be able to say, 'There’s a neighborhood in this town that belongs to our culture and reflects the way live, the way that we laugh, the way that we speak, the way we cook out.," Anderson said. "[Social psychiatrist and author] Mindy Fullilove talks about that trans-generational trauma that’s been passed down through generations by projects like I-94. We're asking ourselves: How about we confront that legacy by building something that reflects our African-American heritage today? This is our Mount Everest; we’re building something that will change lives."