Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Earlier this month, Assemblymember Marc Berman (D-Menlo Park) introduced legislation that dropped the proverbial hammer on the Santa Clara Valley Transit Authority (VTA), Assembly Bill 1091. The legislation would completely overhaul the VTA's Board of Directors by shrinking the board, changing the length of the terms of office from two years to four and banning elected officials from holding seats on the board. Berman's legislation is based on recommendations from a 2018-2019 Civil Grand Jury report from Santa Clara County (PDF) that blasted VTA as the "most expensive and least efficient transit agency in the country."

The grand jury report concluded the poor decision-making of the board has helped create a crisis at VTA. VTA is an agency with high operating costs, low ridership and large deficits compared with peer agencies. Berman worries that the COVID-19 crisis has only exacerbated these weaknesses.

"The grand jury report raised substantive issues about VTA governance and so it is timely to be seeking to address them," writes transit advocate Adina Levin with Friends of Caltrain and author of the Green Caltrain website that covers transit throughout the region.

"The direction to have board members with knowledge and expertise is good. The mix of knowledge to consider should include various forms of professional expertise, and also lived experience with transit ridership and communities using transit," she continues.

The largest of the proposed reforms is to change the makeup of the VTA Board and how it is comprised. VTA is currently composed of an 18-member board with 12 voting members, all of whom are current elected officials in Santa Clara County. The Grand Jury Report stated that directors often have inadequate time to devote to the policymaking and oversight duties of VTA due to their primary focus on the demands of their elected positions.

AB 1091 would reduce the size of the VTA board from 12 voting members to 9 voting members: 5 members appointed by the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors, 2 members appointed by the City of San José, and 2 members appointed by the remaining cities in Santa Clara County. Theoretically, this will lead to the agency being led by members of the public who both have more experience riding transit and professional expertise that will lead to a more functional board.

Defenders of the current practice of having mayors and councilmembers serve on the board note that having elected officials making decisions at VTA increases VTA's power in the region. The agency is not just responsible for VTA bus and rail projects, but also distributing money to municipalities for bicycle and pedestrian projects as well as overseeing some road and highway projects.

Having officials with local land-use powers increases the agency's power allowing VTA to have more say in how transit-oriented development and transportation projects are rolled out in San Jose and other cities. That benefit alone makes the current system a better one than what Berman is proposing, they argue.

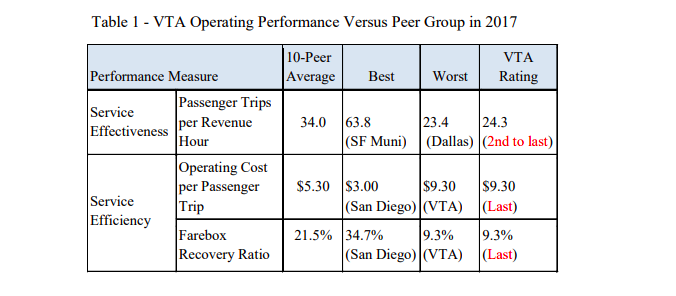

But the grand jury report's findings, that the board needs a major overhaul because the agency itself is underperforming, speaks for itself. The below table shows how the agency ranked last twice and second to last the other time when comparing itself to peer agencies in trips per service hour, cost per trip and farebox recovery ratio.

“One of the points of the report was that the VTA Board doesn’t have the expertise that it needs," says transit advocate Monica Mallon, who frequently attends VTA Board meetings. "Sometimes board members make comments at meetings that show they don’t understand transit, and then turn around and make decisions that impact how millions of dollars are spent.”

The grand jury report provides two options to reform and overhaul board membership. The method Berman didn't choose would have board members directly elected by the public, similar to how the BART Board currently works. While she agrees that the VTA Board needs major changes, Mallon isn't completely convinced that Berman's legislation will lead to the robust changes in how VTA operates.

“It could be better, it could be worse. It depends on who gets appointed," Mallon continues. "Even if the (current) board isn’t composed of directly elected representatives at least someone has the option to vote them out." On the other hand, there's a chance that "they could appoint the kinds of directors that will have the expertise to make better decisions.”

Changing the composition of the board to be mostly based on Santa Clara's supervisor's districts and changing the term from two years to four years may have an even greater impact on how VTA operates than the proposed ban on elected officials. Smaller cities, including Palo Alto, Sunnyvale and Mountain View have long-worried that funding for rail crossings in their cities would get diverted to a BART tunneling project and feel that Berman's legislation could protect them if the BART project experiences cost over-runs.

The report also pointed to the short-terms of board members as a reason for some of the agency's shortfalls. Two years is just not enough time for legislators, who are already charged with a number of other tasks in their jobs, to learn the ins and outs of a transit agency. For some, by the time they are "up to speed" they are already termed out for another regional representative.

Exacerbating the power imbalance between San Jose and other cities, the representatives from San Jose are often on the board for eight years (both of their terms in office in the City of San Jose) giving them more time to build relationships with staff and other stakeholders.

“I like that there will be one person per Supervisorial District," continues Mallon speaking of the legislation. "Another thing that’s unfair (in the current system) is that the mayor and councilmembers from San Jose are there for eight years while smaller cities are cycled around for 2 years.”

AB 1091 could be heard in committee as soon as March 21, although a firm date has not yet been set. Opposition to the legislation is expected from (at least) the City of San Jose and the VTA itself. Nonetheless, Berman's office is certain that major reforms are needed.

"...three Civil Grand Jury Reports over the last 20 years have concluded that VTA’s governance structure is a root cause of the agency’s poor performance and is in need of structural reform," writes Berman in a statement introducing the legislation. "Taxpayers, transit riders, and VTA staff deserve a Board of Directors that have the interest and ability to dedicate the time necessary to provide appropriate oversight and meet our region’s complex transportation needs.”