The 19th Secretary of Transportation may be the first in recent memory to publicly recognize that the need to remove excess asphalt from cities to meet our climate, safety and mobility justice goals — and that the DOT could play a role in right-sizing our road and parking networks.

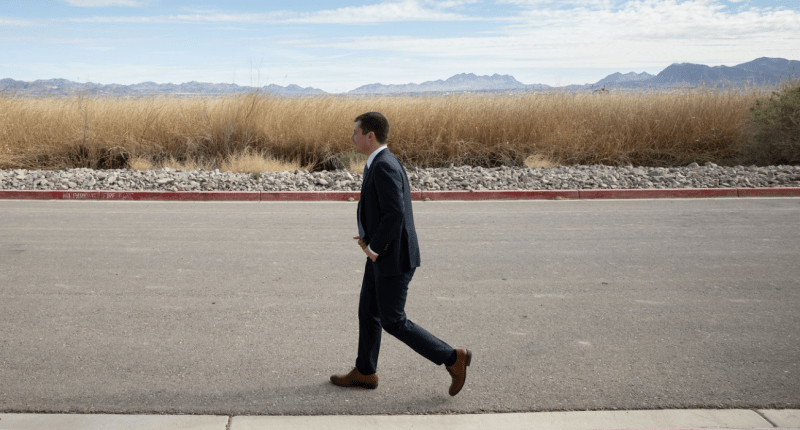

In a brief presentation at the Bloomberg CityLab summit, Pete Buttigieg opined that "there are some areas where, actually, the number of square feet of asphalt in a city probably oughta go down, and we should be supporting that sort of right-sizing." The comment was casual, but it quickly went viral on Twitter — and prompted advocates to wonder whether the DOT might play a role in unpaving American cities under the Secretary's leadership.

Under current DOT formulas, states receive federal dollars based on factors like their total lane miles and the total vehicle miles travelled by drivers each year — a system that all but guarantees that when communities spend those dollars, they'll prioritize expansion over simple maintenance (much less asphalt subtraction) wherever possible, regardless of the harm done to vulnerable communities by urban heat island effects, pollution, traffic violence, and the countless other impacts of overbuilding our road network. Between 2009 to 2014 (the last year for which final data is available), states spent roughly $120 billion on road repair and roughly the same amount on road construction, despite the fact that it should have taken an estimated $231.4 billion every year simply to bring the car-focused streets we already had up to par — a problem that hasn't gotten any better in the years since.

The U.S. DOT and members of Congress alike routinely paid lip service to the notion that states should use a "fix it first" approach to their transportation systems, but have yet to back it up with significant policy reform that would actually require U.S. communities to do it — and needless to say, top officials almost never mentioned de-growing our auto-centric "assets" as a real policy priority.

Yes! Smart transportation planning that requires less asphalt is key to #climateresilience. De-paving over-built intersections, freeways, and parking lots can mitigate urban heat effects, manage flooding, and reduce non-point source water pollution! 🌎🚰🌳🌆 #greeninfrastructure https://t.co/bktJ79QPoM

— Emmett McKinney (@EmmettMcKinney) March 2, 2021

Now, Buttigieg wasn't specific about what, exactly, cities might actually do with all space that we currently devote to the movement and storage of private automobiles — and his suggestion that our asphalt-coated country "probably oughta" cool it with the bituminous for a while isn't quite a radical rallying cry for a full-on degrowth approach, which some advocates think is what our transportation system (and broader economy) really needs to beat climate change.

Still, Secretary Pete's comments were welcomed by advocates of de-paving, which has long been regarded as an important tool for a wide range of advocacy goals — even if cities struggle to find the funds and incentives necessary to wield it at any scale.

Decommissioning even a fraction of our estimated two billion parking spots, for instance, could free up critical space for sorely needed affordable housing, parks, in-neighborhood grocery stores, and so much more; some advocates argue that simply ending local mandatory parking minimums so we don't build any more unnecessary spots would have a seismic effect on American life.

Downtown highway removals — something Buttigieg himself has publicly hinted that he supports — have also been lauded by advocates for their potential to undo the ongoing racist impacts of the federal highway system, at least if the new land that's opened up is explicitly devoted to repairing harms inflicted on Black and Brown communities.

"Secretary Buttigieg is right that many roads need to shrink—or at least make more room for people and business," said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. "In some cases, out-of-date or harmful roadways and highways need to be taken down or completely rethought, particularly the highways of the urban renewal era that plowed through Black and brown neighborhoods displacing the families that lived there. To truly connect Americans to the things they need, the transportation program should focus on maintaining our existing infrastructure, not new assets we can't afford to maintain."

Of course, even thoughtfully removing small bits of asphalt without repurposing that land for other uses can carry benefits, for a simple reason: it reduces demand for car travel, while making streets safer for the vulnerable road users that remain. Simple, asphalt-minimizing road diets, like the Smart Streets initiative that Secretary Pete undertook back when he was the mayor of South Bend, can save lives with little more than paint, landscaping, and bollards.

And while it's less popular among advocates, returning under-travelled roads to gravel actually has more support than you might think; by 2016, at least 27 states had already done it, cutting back their maintenance obligations and freeing up scarce transportation dollars for better things.

Before and after pic.twitter.com/r0v24ZT8O5

— PolReader (@PolReader) March 3, 2021

Of course, Mayor Pete didn't reimagine South Bend's roads alone — and Secretary Pete doesn't have the power to force cities to "right size" their asphalt either, besides helping to persuade Congress to rethink bad funding formulas and pass good bills. But some advocates are hopeful that the nation's top transportation leader could shift the dialogue about what the DOT can do to help cities thrive beyond simply growing their total lane miles.

"I don’t have any illusions about what one person can do to change these entrenched systems – even the Secretary of Transportation," said Daniel Herriges of urban economics nonprofit Strong Towns. "But it opens the door to a more sophisticated conversation, which is not just about what we build and what we maintain, but about what is even worth maintaining. There’s a lot of stuff in the ground that isn’t making communities more prosperous, or making our lives better."