The near total dominance of cars and car infrastructure in American cities aren't just killing us directly in crashes, it's harming us every day through less obvious health effects. "It puts people in a constant state of stress," said Melissa Bruntlett, co-author of Curbing Traffic: The Human Case for Fewer Cars in Our Lives, a new book from IslandPress, during a talk Wednesday morning at SPUR that focused on life in the Dutch city of Delft.

Obesity, mental health, pollution, isolation--cities designed around the automobile contribute in multiple ways to poor health outcomes in North America. As Melissa and her husband and co-author Chris Bruntlett point out, everyone knows this intuitively; it's why people go on vacation to escape the city.

However, "Our cities are meant to be places to connect. They shouldn’t be places we need to escape to recharge," she said.

The pandemic gave North Americans a taste of what cities everywhere could be like--with shelter in place orders, suddenly traffic noise and pollution were attenuated, albeit briefly. "Cities emptied of cars and in their place came sounds of nature and life. And just feeling calm," she explained.

In Delft, where Chris and Melissa Bruntlett currently live with their two children, calm is normal. "When we start to reduce traffic, we start to hear the city," said Chris Bruntlett. They moved to Delft from Vancouver, Canada in 2019 and continue to be amazed by the contrasts.

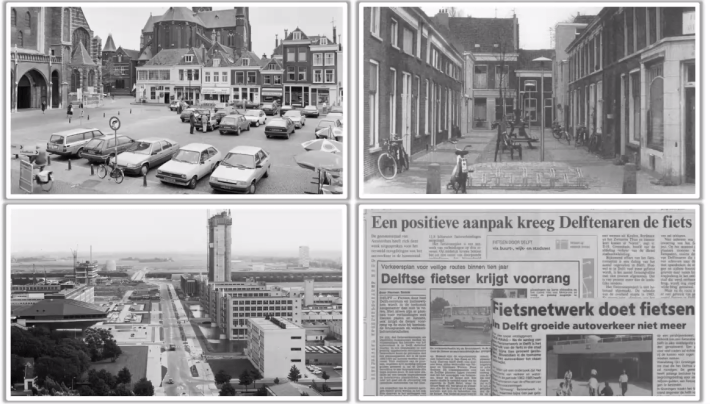

But a calm, healthy, car-light environment wasn't always what defined life in Delft. Below, to the left, is a photo of the same square as in the lead image--during the postwar period when even the Netherlands let automobiles dominate its cities.

As the collage illustrates, it took decades of work to transform Delft into the model city it is today for streets that encourage calm interactions, with people mainly getting around on foot, bicycle and public transportation.

"It was one of the first cities to implement a traffic circulation plan, with a border for livable streets," he added. "It was the first city to establish a cycle network. Later, it was one of the first cities to establish a low-car city center that restricted through traffic."

This has created a more equitable city, where even people who can't afford a car or can't drive have the freedom to move about safely. He adds that expecting the elderly, the disabled, and children to "share the road" with giant automobiles, as is so often the case in North American cities, is ridiculous and unfair. "That’s a power imbalance. We need to make our transportation investment to help people with less power and less mobility."

When cities do that, everyone gains. The disabled no longer have to worry about finding access ramps and safe places to cross streets, since the streets themselves are safe and navigable. If a street is safe for cyclists and pedestrians, including children, then it's safe for people on mobility scooters too, as seen in the photo below:

This also creates an environment where children can range freely without being beholden to adults giving them a ride around town. "We lament the loss of childhood," said Melissa Bruntlett. But equitable transport helps give young children and teens the ability to set their own rules and socialize on their own terms, "...even outside of their age group and peer group. It improves their mental well-being" since they aren't only viewing the world from screens and the back seat of a car.

Opening streets to pedestrians and cyclists also helps reduce people's tendency to mistrust--because on open streets people meet their neighbors and interact with people from different economic and ethnic backgrounds. It also serves the elderly, who can continue to have independence and mobility, even after they become too old to drive.

The Bruntletts insist that the lessons of Delft, a city of 100,000, apply in large cities as well. They cite Barcelona, Paris and other big cities for accomplishing local versions of the same goals. Not to mention the nearby Dutch city of Rotterdam, which famously converted huge car-oriented boulevards into safe streets with greenways, tramways, and protected bike lanes.

Moreover, "You’ve got a great example in your backyard of Oakland," said Chris Bruntlett, referring to the "Slow Streets" programs that quickly turned many street into places where young people could bike and walk without fear of getting run down. In other words, all cities, large and small, can learn from Delft.

"The qualitative benefits of living in a place with fewer motor vehicles was nothing short of a revelation," said Melissa Bruntlett. "Each day we are discovering new joys of living in a place that treats cars as guests."

Be sure to check out the Bruntlett's two books, Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blue Print for Urban Vitality and Curbing Traffic: The Human Case for Fewer Cars in Our Lives, both from IslandPress,

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.