Most Americans agree its past time to green the nation's fleet of yellow school buses, a new survey finds — but Congress keeps whittling down funding for this common-sense, bipartisan priority.

In a recent study commissioned by the American Lung Association, pollsters found that 68 percent of American voters expressed support for as much as $25 billion in federal investment into school-bus electrification, including a majority of Democrats and Independents and a near-majority of Republicans.

That's more than the $20 billion Biden initially proposed for the initiative in the first draft of his infrastructure package, the American Jobs Plan, which also included $25 billion for electrifying city buses, although both numbers have shrunk during negotiations with the Senate. The most recent framework for the bill includes just $7.5 billion for bus electrification, and it's not clear whether those dollars will go toward greening city-bus fleets, school-bus fleets, or both. Considering that $20 billion would be only enough to convert 20 percent of the nation's school-transportation fleet to clean power, it won't stretch very far.

Advocates say the cuts are unacceptable, especially given growing support for zero-emission fleets.

"The public instantly understands the connection between diesel pollution and kids with asthma on buses," said Paul Billings, senior vice president of public policy at the American Lung Association. "And increasingly, the understand that e-bus tech is not something that will be available in the future — they know it's there today."

School buses aren't always a focus of sustainable-transportation advocates, but they represent the largest segment of America's mass-transit system, outnumbering city-transit vehicles by more than three to one and outpacing mass transit's annual trip volumes by roughly a million journeys every year. But because 95 percent of school buses run on diesel, the 20 million U.S. children who use them gain exposure to emissions that are harmful to respiratory health and brain development.

Despite broad consensus on the importance of school-bus electrification for public health and reducing climate change, finding the money to do it at scale has been difficult. A patchwork of federal and state programs offer modest subsidies to states (and, more rarely, to school districts directly), but oil and auto-industry lobbyists have fought the kind of transformative funding that experts say is necessary to green the sector.

The average electric school bus costs $312,600, compared to just $110,000 for diesel, but it can save its operator as much as $130,000 in fuel and maintenance costs over its 16-year lifetime.

"What we're talking about is a disruptive technology that will change the way we move people and goods from place to place forever," said Billings, "As positive as we all know electric buses are for clean air, and climate, and creating jobs, there are always entities out there that would continue to sell combustion engines."

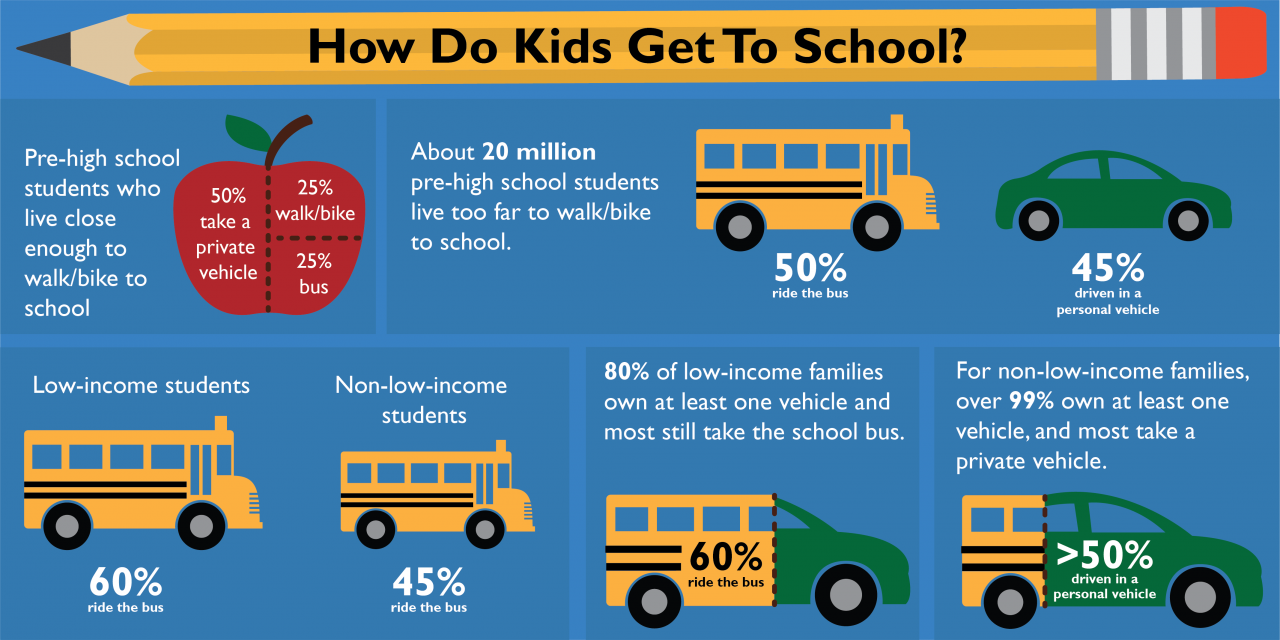

Those obstructions are even more unacceptable given the U.S.'s growing dependence on automobiles, which forces more and more children to give up walking or biking to school every year. But as children from wealthier families are piled into cars, low-income kids are shifted onto buses, further concentrating the health effects of diesel pollution into poor and BIPOC school districts. The Bureau of Transportation Statistics recently reported that 50 percent of American kids now take the bus to school, up from just 39 percent in 2009 — but a 60 percent of low-income families do so, in part because 20 percent of their parents don't own a private car, and many more don't reliably have access to a vehicle.

"Air pollution discriminates," adds Billing. "People of color are three times more likely to live in counties that get failing grades on levels of ozone pollution, as well as both annual and daily particle pollution levels. We've made tremendous progress in cleaning up air in our communities, but that progress has not been enjoyed equally, thanks to systemic racism that puts communities of color adjacent to major roads, downwind from major refineries, and at schools where a lot of kids are riding these dirty buses. Then, on top of that, they have less access to affordable, quality health care, too .... Any money we get really needs to target these funds into communities with the greatest burden."

Image: National Center for Safe Routes to School

Convincing lawmakers to help electrify city buses is even more daunting, thanks to the logistical challenges of fueling and maintaining long mass-transit routes. Advocates have applauded a $4 billion transit-electrification program in House Democrats' surface-transportation-reauthorization bill, the INVEST Act, though most experts say the U.S. needs far more investment, along the lines of the $73 billion sought through Sen. Schumer's Clean Transit for America Plan. So far, none of the Senate's proposed reauthorization bills contain any money for a green school-bus transition; advocates worry that even the $7.5 billion in Biden's infrastructure package could become a bargaining chip in negotiations.

Still, Billings says that, with advocate pressure, e-bus funding could get a federal boost — and e-schoolbuses would be a wise place to start.

"If we're going to electrify transportation, we need to show we can do it anywhere," said Billings. "School buses are particularly ubiquitous in U.S. communities, and that means they have a lot of potential to help the public understand the advantages of this transition But then we need to do it with urban transit, too — because the public health impacts are exactly the same."