Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

* PUT * THE * RIDERS * FIRST *

It seems like a simple notion, but that was the main takeaway from a Tuesday evening SPUR talk on transit integration.

"Start with the fundamental needs of the passenger base that's there," said Peter Rogoff of Sound Transit in Seattle, and one of the panelists. He said to step away from the political structures and focus on what customers need. "Look at it as one universe of transit riders."

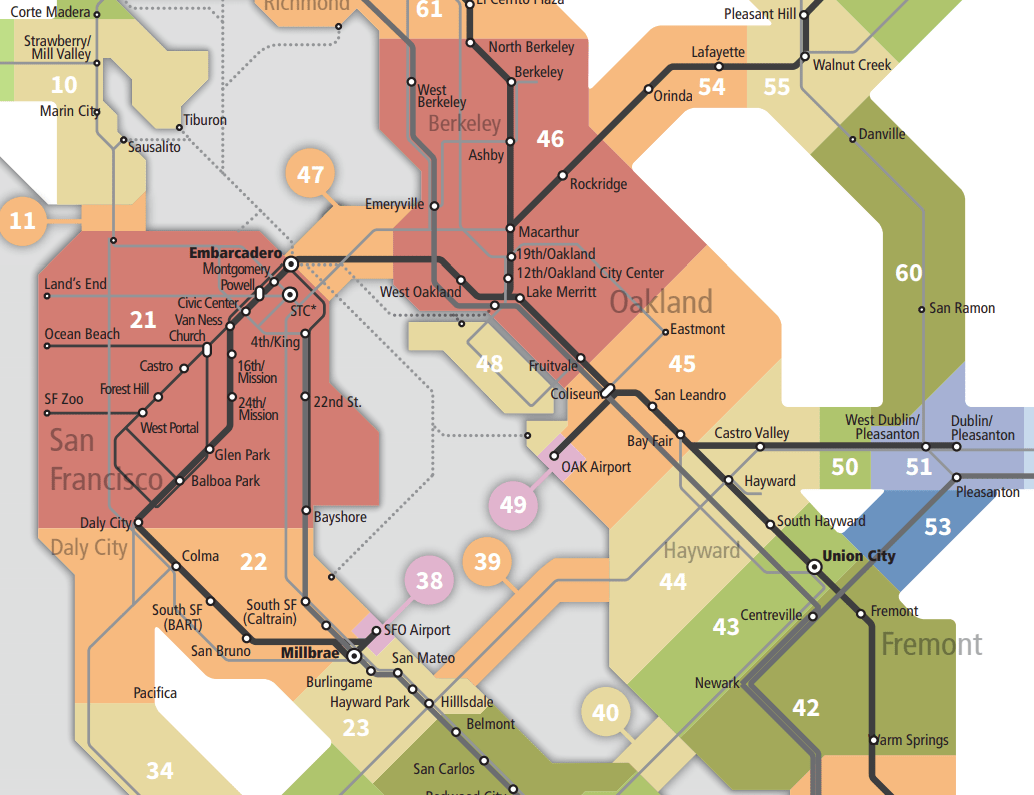

The question is how to do that. Trying to integrate the 27 operators in the Bay Area under a single, umbrella fare structure may seem overwhelming. But integration didn't come easily in any city, and has had political obstacles everywhere, explained the panelists. Even in places that are better integrated than the Bay Area, the fight to integrate better continues. Kevin Desmond, formerly of New York's MTA, remembers when there weren't even transfers between bus and rail operated by the same agency in New York. "The bus and the subway people were as if from a different planet. If you had to take a bus and then a subway you had to pay full fare for every trip."

But eventually that was solved with MetroCard, New York's replacement for tokens and its version of Clipper. The change lead to a huge growth in revenue and ridership. Such improvements should be seen as ongoing; New York is now working on an "OmniCard" that will include the Long Island Railroad and MetroNorth commuter railroads, at least within the city limits.

There is no single model for the Bay Area to look to, said Desmond, because of differences in historic governance structure. However, there are best practices that can be copied. "As we all build back from COVID, we do not and should not recreate what we had before the pandemic," said Rogoff, noting that the emergency and its financial pressures should be embraced as an impetus towards integration. Sound Transit overseas four different agencies, he explained. "Community Transit, King County Metro, and Pierce Transit to the South, and the Washington State Ferry System... during COVID we coordinated in ways that were unprecedented."

"During COVID we were talking to each other every day, so if we were all going to go to rear-door boarding on our buses, we wanted to do it together," he explained. They also decided to eliminate fares as soon as one of the operators had COVID cases among their operators. They also coordinated on routes, so if one agency had to eliminate a line, another agency could pick up the slack. For example, when a local bus operated by one agency was cut, another agency converted its express service into a local to make sure riders weren't completely stranded. Part of that cooperation is because all of the agencies are beholden to the region's taxpayers via the Sound Transit umbrella, so if one region doesn't get good service, it becomes impossible to fund any of them. "We get revenues approved from the taxing districts in all three counties."

"There is no perfect model," agreed Leanne Redden of the Regional Transportation Authority of Chicago. But she said creating integrated transit depends on "political champions who will drive what it's going to look like." She explained how Chicago RTA, an umbrella organization formulated in the 1970s and 1980s, originally oversaw a multitude of bus operators, suburban commuter rail districts, and the Chicago Transit Authority, which operates the L. Now, through consolidation, it oversees just three agencies. As in Seattle, RTA is the sole taxing authority created by the state legislature. "We strictly think about the region as a whole," she said, while the individual agencies they oversee deal with the day-to-day operations of trains and buses.

"In Toronto we've got ten agencies and we move 750 million riders annually," said Phil Verster of Toronto's Metrolinx, that city and region's umbrella transit organization. "Whatever we need to do... the customer is first." He added that it's important to merge only activities that are better delivered across the region, such as planning and regional fare cards. "Lastly, think about efficiencies--but don't assume bigger is better." For example, regional and local buses don't necessarily integrate well.

In the end, they all agreed it comes down to individual leaders who, unfortunately, sometimes won't get on board with a customer-first focus. They have to either get with the program or get lost. "Some times it's individual board leaders and agency heads who think they should be the big dog, and that really is a waste of time," said Rogoff.

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.