Nik Kaestner, the former Director of Sustainability for the San Francisco Unified School District who pushed for a Dutch-style roundabout near a school in Mission Bay, moved to Berlin earlier this year. He was so impressed with Berlin's recent transformations that he started blogging about it. He asked Streetsblog San Francisco to cross-post his reflections on the impressive accomplishments of his new city.

I recently came across this article about Berlin, and was fascinated by some of the author’s findings:

Berlin has the highest share of people walking, biking, and using public transit to work (86%) of all European capitals. Not surprising, considering only one third of Berliners own a car. Astoundingly, there are more people biking in Berlin than in the four other major European capitals combined! Read it and weep, Paris, London, Rome and Madrid. ;)

There is no shared mobility concept you won’t find in Berlin. That’s for sure! With thirty-three different providers and over 50,000 vehicles, Berlin has the most of any city in Europe. This includes scooters, bikes, mopeds, cars, vans, and shuttles, most of them electric. And several of these can be easily booked on the world’s largest mobility-as-a-service platform, Jelbi, which also includes taxis and transit.

No other European metropolis offers more inner-city forests, parks, and lawns. Officially, the stats show Stockholm, Barcelona and Moscow ahead, but each of these has a huge forest at the edge of the city limits that is not within reach of most residents on a daily basis. In Berlin, there are parks, playgrounds, and trees around every corner and in the middle of many blocks!

But Berlin also has wide streets and plenty of cheap parking ($12 annual parking permit, anyone?) that validate the supremacy of the car. That’s because Berlin was largely destroyed during WWII and built up as a car-first city, much like Rotterdam. Consequently, Berlin’s transition away from car-centrism might hold more lessons for the US than older European cities with an ultra-dense urban core.

What are those lessons? Berlin is in the middle of a multi-year effort to implement its vision of a livable, climate-friendly metropolis of the future, and four initiatives are particularly relevant to an American audience.

MOBILITY ACT Transit First on Steroids

San Francisco voters passed its Transit First policy back in 1973. Thirty years later, San Francisco’s commute driving rate had actually increased from 42 percent to 51 percent. While there has been slow but steady progress since then, even to this day, the pitchforks come out whenever a new bulb-out, bike share station, or transit lane is proposed.

Berlin passed its Mobility Act in July 2018 in response to a public initiative in favor of more bike infrastructure. The Greens had recently come to power as part of a center-left coalition and were ready to implement many of the ideas that advocates had been asking for.

The Act lays out numerous goals and projects to support a safer, more livable, more climate-friendly city:

- increase pedestrian safety

- calm neighborhood traffic

- improve the bike network & parking

- promote bike sharing & cargo bikes

- build out the public transit network

- replace & electrify the fleet of buses, trams, and trains by 2030

- build out the EV charging network

All of this is backed by a budget that has (almost) doubled to 2.1 billion Euros per year and an additional 28 billion for the new public transit fleet. Impressive.

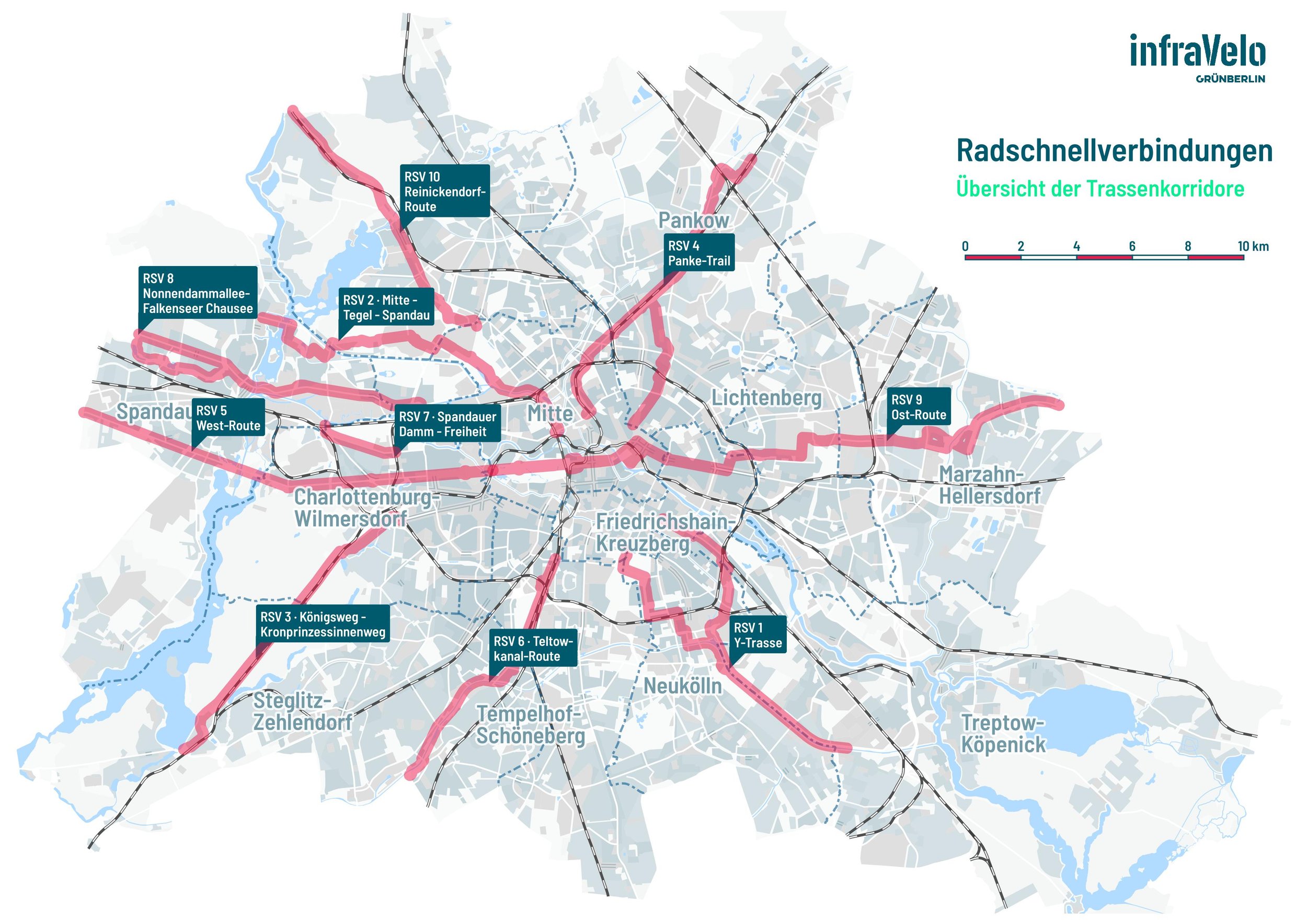

After the Mobility Act was passed, Berlin built up its capacity to deliver livable streets projects and initiated planning efforts to make them a reality. The pace of this ramp-up has not placated livable streets advocates, although in my humble opinion there is nothing to complain about. Check out the number of projects being planned by the newly established bike agency, InfraVelo, including parking infrastructure, this new bicycle bridge, and a network of bicycle highways. Berlin also recently passed Germany’s first pedestrian law, approved a bike master plan that includes 3,000 km in total bike lanes, and agreed to an expansion of the U-Bahn, S-Bahn, and Tram networks.

Where does Berlin plan to get the money? The city is currently subsidizing half of transit operations (the rest comes from ticket sales). Going forward, this will be augmented by higher residential parking fees and expanded curbside parking management as well as a mandatory tourist transit pass. The latter has the benefit of raising revenue as well as encouraging tourists to get around without a vehicle.

Other plans of the re-elected Red-Green-Red coalition government include the removal of two stretches of highway in Berlin’s west, fast-tracking transit projects, an increase in the number of play streets and traffic-calmed neighborhoods (see below), and street closures around schools during drop-off and pick-up. On the flip side, the Social Democrats also managed to include the construction of a new boulevard in the eastern part of the city, much to the chagrin of the Greens and their supporters. The latter have been pushing to repurpose the current extension of the A100 highway, but were only able to prevent the next section from going into planning.

LESSON FOR SF: Say it like you mean it and support it with the big bucks!

KIEZBLOCKS From Cut-Through to Urban Oasis

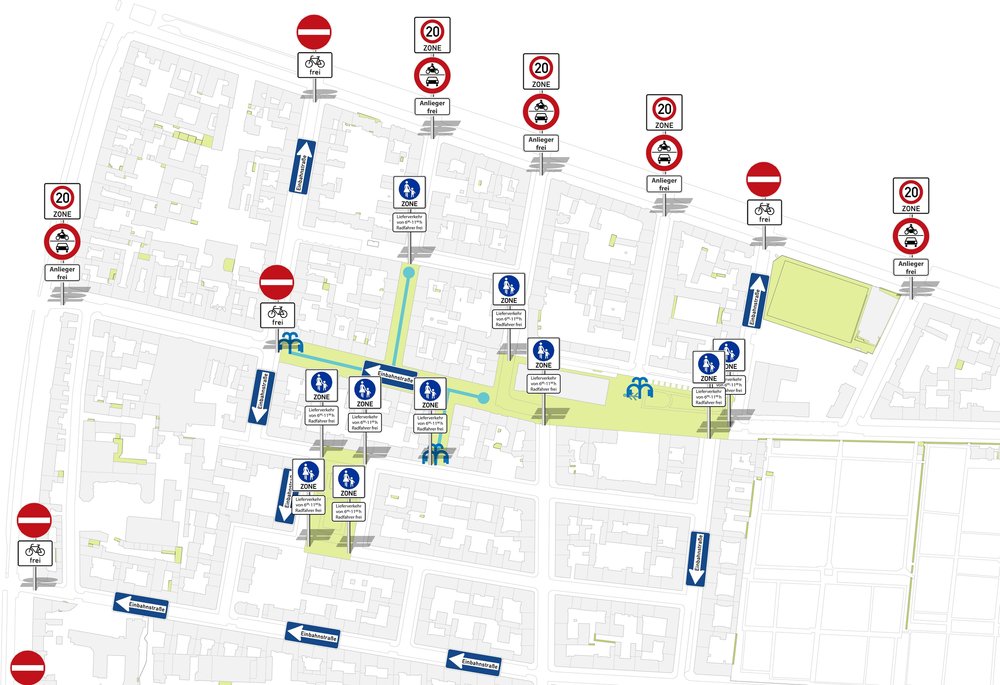

Barcelona has its Superillas, Berlin has its Kiezblocks. A Kiez is the Berlin term for neighborhood, each one of which is generally centered around a commercial street and can best be equated with the concept of a fifteen-minute city. Kiezblocks are traffic-calmed neighborhoods in which cut-through traffic has been eliminated to increase safety and allow neighbors to enjoy the streets for other activities. Often these go hand-in-hand with play streets, which are (usually temporarily) closed so families may enjoy some quiet playtime in front of their apartments.

That’s why the nonprofit Changing Cities, which grew out of the successful bike initiative, has created tools to help neighborhoods develop traffic calming plans, collect signatures, and submit their proposals to their local district administration. So far, over 50 of 180 possible neighborhoods have begun organizing.

Changing Cities is also advocating for two Kiezblocks to be created in each Berlin district per year and for design guidelines to be created and adequate staffing to be provided by the city. In the meantime, the Verkehrsclub Deutschland, an alternative German AAA, has developed toolkits to help citizens “retake the streets.” Several other organizations support a similar transformation, including one effort - Parking Day - that will be familiar to San Franciscans.

One of the first Kiezblocks to near the finish line is in Bergmann Kiez, where I used to live. After testing a variety of treatments to calm traffic, the district administration has approved the plans and completed a transitional makeover, complete with removal of parking spots, temporary bike boulevard (see below), and an overhaul of traffic flow.

The next step is a complete removal of cars from the space, creating a pedestrian zone the likes of which does not exist in Berlin due to its historical destruction.

LESSON FOR SF: Empower neighborhoods to pilot the change that’s still too difficult at the city level.

REALLOCATING SPACE Better Transit Is Not Enough

Whenever I suggest to friends that we need to take space away from cars, a common response is, “I’ll be happy to switch to a bike or transit as soon as the former is safe and the latter is reliable.” Amazingly, you’re just as likely to hear this refrain in Berlin as in San Francisco, despite the fact that the U-Bahn comes every five minutes and you can grab a bike or scooter on nearly every corner and ride it on largely separated bike lanes.

What can we learn from this?

- There will always be an excuse. There are a million reasons why now is not the time to ask residents to accept major changes: inadequate transit frequency, incomplete bike network, the pandemic, financial hardship, mistrust of government, city finances, lack of adequate staffing, etc. No major city project is without its doubters when it’s first proposed.

- The situation will not improve without limiting car use. One of the most important ways to meet the needs of reluctant would-be bicyclists and transit riders is to improve these two experiences. Riding a bike or taking transit has to be the most convenient and/or fastest way to get to your destination. The only way to do that is to provide these modes enough space to allow for a safe, quick, and seamless travel experience. And that means removing vehicle lanes to create bulb-outs, bike infrastructure, transit lanes, and so forth.

- You just have to dive in. Mayor Hidalgo of Paris, as well as many other bold and brave city leaders in such places as Pontevedra, Ghent, Barcelona, and yes, the Netherlands, have shown us that citizens generally support efforts to make cities more livable once they see what a positive impact they can have on the ground. That’s why she was overwhelmingly re-elected to a second term. Had the Mayor backed off when the resistance first appeared, Paris would not be the much-improved city it is today.

In the case of Berlin, signs of the reallocation of space, which has gathered pace since the pandemic, are everywhere. The new district administration in Mitte has agreed to remove a quarter of the parking spots in the center of the city. Tempelhof-Schoeneberg is not far behind, with an initial ten percent cut. And the biggest shopping street in southwest Berlin, Schlossstrasse, is becoming car-free on Sundays and having parking spots replaced with a wider sidewalk and loading zones.

Back in Mitte, Friedrichstrasse has already been converted to a car-free shopping street:

Berlin has also discovered the beauty of parklets:

The aforementioned Bergmann Kiez has added a new, two-way bike lane:

Below is the entrance to a parking lot that has been repurposed as a mid-block cut-through for cycle traffic.

The famous boulevard Unter den Linden is losing two vehicle lanes.

And all around the city, streets have been handed over to citizens to hang out, shop, play, chat, eat, drink, or simply get from A to B.

LESSON FOR SF: Don’t stop at parking spaces, reprogram the whole darn street!

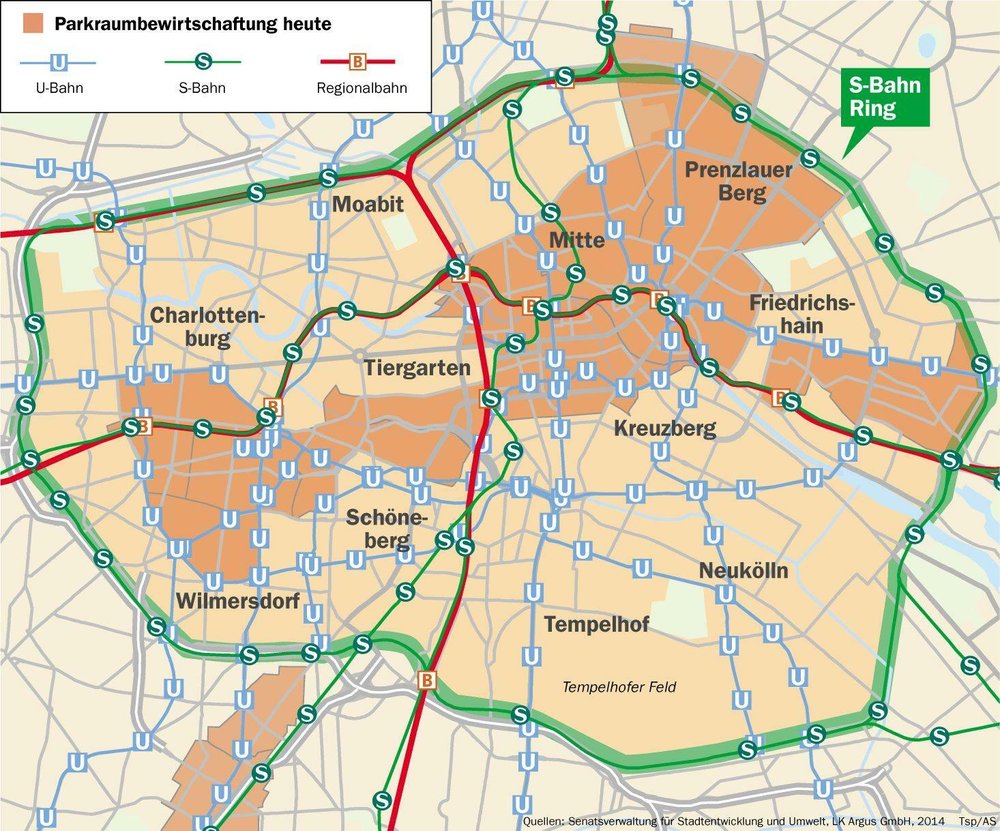

AUTOFREI BERLIN Largest Car-free Zone in the World?

Because of its postwar reconstruction and Soviet-style architecture, Berlin’s streets and sidewalks are generally wide enough to accommodate pedestrians, bicyclists, and cars. It is for this reason, perhaps, that the movement to re-imagine space allocation in dense, overcrowded cities has been slow to take hold here. But citizen activists have watched ambitious mayors in other European cities implement one innovative urban planning idea after the other and are launching an initiative that would create the largest car-free zone in the world, slightly smaller than the City of San Francisco or London’s zones 1 & 2.

The goal is to all but eliminate private vehicles within the Berliner S-Bahn Ring or, as organizers put it, to “ensure that the public streets in Berlin are fairly apportioned, healthy, safe, livable, climate- and environment-friendly.” After a transition period of a few years, the use of non-federal city streets would be limited to walking, cycling, and public transport (the so-called "Umweltverbund"). Persons with reduced mobility, public service vehicles (police, fire, sanitation, etc.), and commercial or delivery traffic would still be allowed to drive on city streets. Other users would have to plead hardship or be limited to twelve trips (vacation travel, runs to IKEA, picking up grandpa from the train station) per person, per year.

The initiative got underway in October 2020 and pro bono lawyers crafted a legal statute that was cost-estimated by city officials. At the end of April, organizers launched a three-month campaign that netted over 50,000 signatures in support of the ordinance. Now, the proposed law will be debated by the Berlin city council. If it chooses to adopt the bill or the majority of its provisions, as happened with the bike referendum in 2016, implementation of a car-free Berlin could start as early as next year. If, however, the city council is not convinced, organizers will have to collect another 175,000 signatures to put the initiative on the ballot in 2023.

LESSON FOR SF: Dream big. Oh wait, you already are. Now make it happen!

The pandemic has provided the opportunity for planners and city officials to reassess how their cities are organized. Slow streets have gone in, restaurants have spilled out onto sidewalks and parking spaces, and temporary bike lanes have been created. But the pace of change, as rapid as it has seemed, is not quick enough to meet our climate obligations for the next ten years. Even more radical thinking is needed, as is being proposed in New York City and Berlin, being implemented in Paris, and being dreamed up by Jan Kamensky!

Does San Francisco have the courage to follow in their footsteps?