Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Narrow, crooked streets. Historic, medieval buildings. Older, legacy subway lines to go under. These are all good arguments for building a new subway line in very deep tunnels under a city. And that makes sense in cities such as Paris, Tokyo, or London.

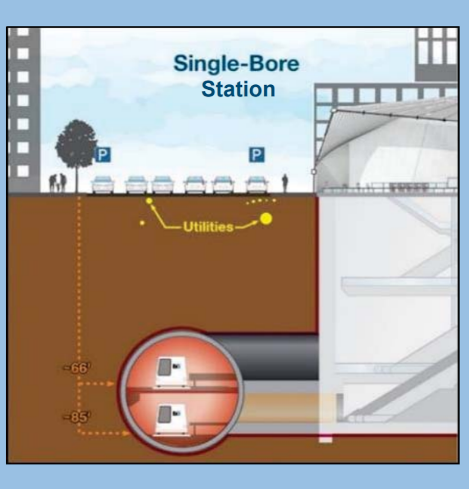

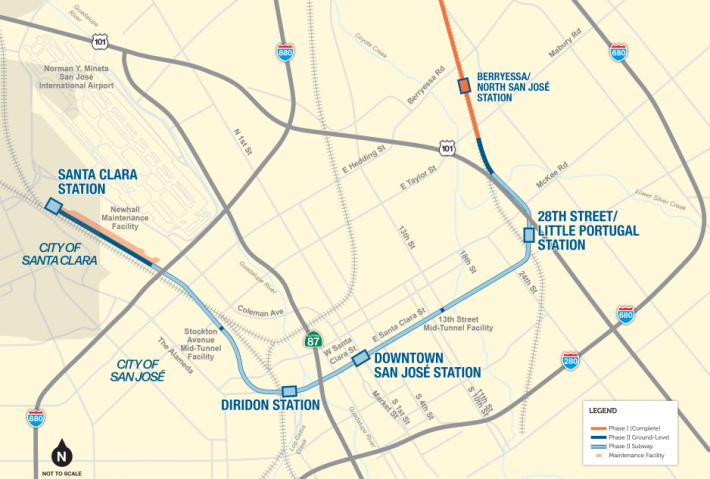

But San Jose has none of those things. With its wide, straight streets, it is precisely the situation where construction should be done as near as practical to the surface. And yet, according to a new report from the Federal Transit Administration, San Jose is now on track to building a six-mile subway extension that could cost over $9 billion--some $3 billion more than projected--in large part because they plan to put it in an enormous, single-bore tunnel constructed six stories under the street, one track stacked above the other, as seen in the lead image.

In 2018 the Valley Transportation Authority approved a deep, single-bore tunnel plan to appease merchants who were afraid of surface disruption from construction, as happens with light-rail or bus rapid transit (to some vocal merchants, everything should be built underground, and the deeper the better). The deep bore scheme was sold as a less disruptive, "cheaper" option, something that appears to be inaccurate. "The FTA did a conditional approval of VTA's phase 2, but in that approval, they said they're underestimating the cost," explained the East Bay Transit Riders Union’s Derek Sagehorn. "It's more like $9 billion instead of $6.5. The VTA is strenuously denying that cost."

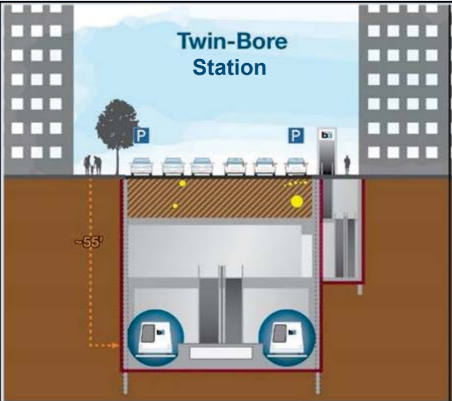

Cost projections are up in part due to the fact that such a deep, single tunnel subway requires more fire and other safety considerations. It's also more complicated to do transit-oriented development, because it's harder to have multiple entrances to the station and good integration with surface buildings. And the stacked configuration, with the tracks placed above each other, complicates single-tracking operations--trains can't switch back and forth to get around a disabled train or to allow for maintenance unless builders also include enormous ramps to get trains between the two levels.

The deep-underground scheme is also less inviting to users since several minutes will be wasted just getting up and down from the stations.

This is what San Jose City Councilmember Raul Peralez, who helped lead the drive for a single-bore project, wrote in an editorial in 2018 when the decision was made to go with a single tunnel:

...in a few weeks, both VTA and BART will either approve an innovative and safe single-bore project that will not require our public right-of-way along Santa Clara Street to be torn up, or surrender to the twin-bore status quo that could potentially cause reprehensible damage to our businesses and the demise of a downtown that has finally caught its stride.

Some may call me melodramatic but I have seen firsthand during my short time here in office how a public transit project gone wrong can ravage a business corridor. Three years ago, business owners were banging at my door, infuriated at how their businesses were plummeting due to the Bus Rapid Transit project that left the streets their customers depended on in complete disarray. Mind you, that project only encroached a few feet beneath the street surface. I cannot begin to fathom the damage a 40-foot deep by 1,400-foot long void would cause, just so we could accommodate twin-bore tunnels, when really we could achieve the same safe result with single-bore. Those who have invested time, talent and treasure into our downtown deserve better.

Streetsblog has reached out to Peralez to see if his views have changed or why he is conflating a subway project with Bus Rapid Transit, which is entirely on the surface. Streetsblog will update this post.

Meanwhile, Portland, Los Angeles, and other cities have set up funds to help offset disruptions to businesses during transit construction. L.A.'s Purple Line extension, which is similar to the BART extension in many respects and is being built with traditional, twin bores, has a fund of $10 million annually to offset merchant costs. Helping merchants, either with marketing, loans, and or grants makes way more sense than spending billions on a far less proven deep, single-bore method [note: merchant profits generally increase when new transit lines are finished and the stations open. If merchants ultimately profit from the subway, they should be required to return what they received to get through the construction period--that should be a condition of taking these funds].

Importantly, the shallower, twin-bore, with better access to the surface, will result in a better system for riders. That's something Peralez and others supporters of the deep, single-bore scheme don't seem to understand or value, perhaps because they don't ride transit themselves, except on rare occasions. But from a user perspective, you want a system that's as easy as possible to access from the surface; deep tunnel schemes run contrary to that goal.

"Now that they see the rider experience and urban design that they're missing, they have an opportunity to look back at the twin-bore design and see if that would do a better job," said advocate Adina Levin in a phone interview with Streetsblog. "The single-bore seemed attractive because it was innovative, only the second such design in the world. But innovation is good if it's delivering what you want. If it's new but not delivering the outcomes you want, then it's not the right thing to do."