Nica Cave was rolling along in her wheelchair on one of Denver, Colo.'s busiest corridors — five-lane Sheridan Boulevard at 17th street — in the middle of the afternoon on February 9, just inches from oncoming traffic. Cave, 25, uses a wheelchair due to a lifelong disability, and frequently makes journeys like this to get from A to B.

But on that day, she was not alone: she was on a walk organized specifically to draw attention to the dangers experienced by people who walk and roll on Denver's streets, alongside state transportation engineers, city planners, and youth advocates curious to see what her daily experience as a car-free wheelchair user was really like.

Cave co-hosted the event with Jonathon Stalls, creator of the popular TikTok account “Pedestrian Dignity,” along with Phyllis Smack, Alejandra X. Castañeda, and Max Leal-Gomez.

“It is important to be clear about how profoundly unsafe our route is,” Stalls wrote in a planning email.

@pedestriandignity ✨ SO proud of @phyllissmack all the youth/student voices (Nica, Max, Justin, Sam) that moved w/our walk, roll & transit event yesterday w/state & city transportation staff/directors. 🗣 Inspire & pressure YOUR agencies to walk/roll/bus YOUR streets! #pedestriandignity #urbanplanning #publichealth

♬ Forever - Labrinth

In his work, Stalls, 39, focuses on highlighting the “lived experience” of the most vulnerable people on our streets. In his previous activism, he often hit (figurative) road blocks, struggling with “too much conceptual convincing.”

But TikTok — which he said “is not natural to me in any way” — gives him a fresh approach. He says the platform helps his viewers to more directly experience what it's like to navigate car-dominated streets on foot, or using an assistive device like a wheelchair. He also maintains a YouTube channel; in 2021 he submitted a video of a particularly arduous trek to a Littleton, Colo. bus stop to Streetsblog's Sorriest Bus Stop contest.

“I want them to be engaged with their senses,” he said.

And Stalls says young people are responding — not just by clicking "follow," but by becoming activists, joining planning commission meetings, sending videos to city council members, and organizing events. He notes an earlier video that he filmed on Sheridan, which prompted "at least 100 or more" emails to the Colorado Department of Transportation urging the agency to make the road safer.

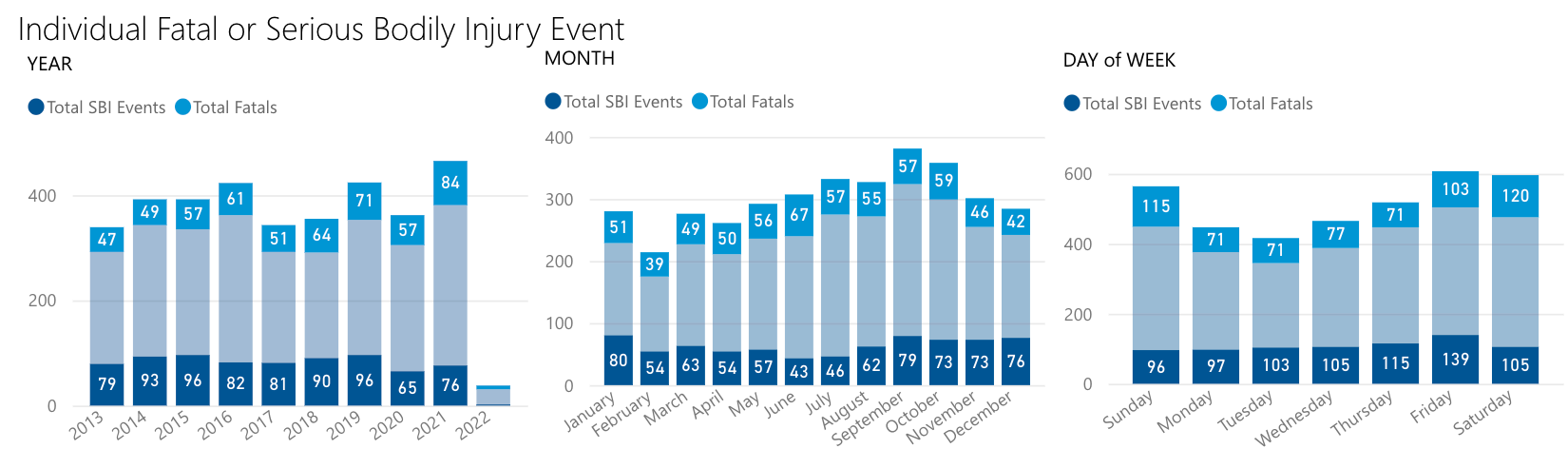

With Denver's roadway deaths on the rise, the Mile High City needs new street safety advocates more than ever. A staggering 73 people died in traffic crashes last year, more than any other since the city first adopted its Vision Zero plan in 2015.

Those numbers caught the attention of state transportation authorities — as did the flood of emails from Stalls' Tik Tok followers. But when Colorado DOT leaders reached out to discuss his work, Stalls' response was unconventional: “I would prefer if we actually...go out and move on these arterial streets together while we think about and co-create and think through solutions, and not just talk about it,” he said.

The state officials agreed, and Stalls and his co-hosts invited them to spend an afternoon on one of the busiest corridors in the city, to experience its missing sidewalks for themselves.

“There are muddy hills that slope and spill right into a high-speed arterial street where cars move 40 to 50 miles an hour,” he said, adding that the thoroughfare runs adjacent to grocery stores, public housing, and mixed-income housing.

At the event, Cave introduced her co-hosts and facilitated conversation with DOT officials. Her goal was simple: to help others “witness my experience being a pedestrian in the roughest parts of Denver.”

Cave said wheeling down the road so close to oncoming traffic “was a little terrifying...[but] I do experience that on a daily basis.” Being with the group “amplified the experience,” she added, because it helped others to see what things they'd normally miss from the car window.

“Going from A to B is not as simple as looking at the bus routes and the times,” she explained. “It’s going on Google Street View and looking at the crosswalks, looking at the sidewalks, looking at entrances in the buildings, looking at bus stops – and making sure that I can verify that they're actually going to work for me.”

Sometimes, even those exhaustive efforts fail her, forcing Cave to adapt on the fly. She jokingly calls herself a "logistics expert,” because of all of the planning involved in getting where she needs to go.

Denver transportation leaders are taking some steps to improve conditions for walkers. In 2018, a citywide plan called “Denver Moves: Pedestrians and Trails,” offered a blueprint for improving crossings, sidewalks, and trails throughout the city. And the Elevate Denver Bond, includes $47M in funding to help fix sidewalk gaps – including for sidewalks along Sheridan Blvd from I-70 up to 52nd Avenue, where the Feb. 9 walk occurred.

A 2021 RISE bond offers another $12M to construct missing sidewalks and $42M for safety and mobility improvements, according to the department. Additionally, the department hiked parking rates from $1 to $2, and the additional revenue will go towards implementing a Vision Zero Action Plan to build more bike lanes, fill sidewalk gaps, and make intersections and pedestrian crossings safer.

Those efforts will help, but keeping all those new walkways in good working order will be a challenge. Cave says there are inconsistencies in who is responsible for sidewalk maintenance under Denver law, and that she thinks placing ownership in the hands of the city would be the best solution, “because they are public spaces.”

She also thinks DOT leaders should make walking Denver roads a regular practice — and Stalls agrees. He says the experience of “being in a hostile environment” should be at the forefront of the minds of city planners as they plan initiatives, too, rather than “an afterthought.”

“We don't need a fucking study,” Stalls said. “People are dying.”

Hope Reese is a freelance journalist based in Budapest whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Vox, The Atlantic, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @hope_reese.