Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Twenty-one people have been killed on the streets of San Jose since April 6. "This is just since the last meeting," said City Councilmember Raul Peralez, chair of the city's Vision Zero Task Force, a group of politicians, officials, and advocates, during its regular meeting last Wednesday. Despite the appearances and slogans, local advocates tell Streetsblog the city has abandoned any serious efforts to reduce these numbers.

At the start of the meeting, Peralez and another task force member read the names of the victims. In addition, some forty-five people have been killed this year so far. Sixty people were killed in 2021.

But apparently, San Jose officials think the solution is to go back to "shared responsibility" and victim blaming. For example, here's one solution offered to reduce those figures--handing out flashlights and reflective vests to un-housed pedestrians:

"It's kind of laughable," said the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition Diana Crumedy in a phone interview with Streetsblog. "What research data did they receive that this would be a game changer?"

"It's the ultimate pat-yourself-on-the-back move," said San Jose bike advocate Robert Gonzalez

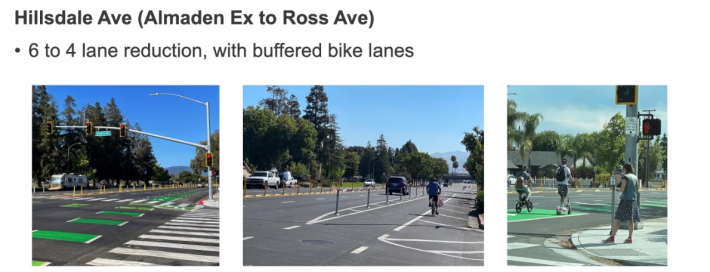

Crumedy and Gonzalez told Streetsblog that city officials are falling back on failed policies and educational campaigns while neglecting serious infrastructure changes that could actually make a difference. When infrastructure projects do happen, they're now soppy, paint-and-post installations that don't even try to force motorists to slow at corners. Case in point: at the Vision Zero meeting, San Jose DOT's Vu Dao talked about how on Hillsdale Avenue they have "completed 2.3 miles of quick-build enhancements." To illustrate, he showed pictures of the work (see the lead image and the pictures below from his presentation).

He referred to these as new and “high-quality” bike lanes. Note this is a four-lane road and cyclists are protected in these pictures by paint and little plastic posts that couldn't possible stop or even delay an errant motorist. Readers will also note there's no protection extending into the intersection, aside from paint. "It's a nice feel-good commentary, but it's just a buffered bike lane on a stroad with very fast traffic," said Gonzalez, shortly after riding it. "It's similar to what they did on San Antonio, with some parking-protected lane on a small stretch, but the rest of the stretch is just not protected. They're celebrating it as a huge deal, but it sucks."

He added that the reason it isn't fully protected is the same one Streetsblog readers hear over and over again: "Residents got rid of the parking protection," said Gonzalez, because it would have meant a loss of street parking.

"San Jose knows that protected intersections and bike lanes reduce fatalities and crashes, yet it has not implemented many corners and intersections for the last few years," said Vignesh Swaminathan, a consultant who helped design the city’s impressive quick-build network downtown, in an interview with Streetsblog. He also reports that the Dutch-style installations that he managed in 2019--which were supposed to be converted from quick-build to protective concrete by now--have been allowed to deteriorate (see images below from 2019 and 2022 below).

Committee vice chair and San Jose City Councilmember Pam Foley's asked Dao at the meeting why only short segments of Hillsdale's new bike lanes were protected by parked cars. "We can sandwich the bike lane between the curb and parking to protect the bicyclists" in only a few areas because on most of the street bus stops and driveways make protected bike lanes impossible, Dao responded.

Of course, that's complete nonsense. It's actually about the loss of parking required to make protected lanes, intersections, and bus stops, as Gonzalez pointed out.

As this post and video from the Netherlands clearly shows, protected bike lanes co-exist with driveways just fine, but, yes, it requires eliminating parking spaces to maintain sightlines. Bus boarding islands--which can also be installed via quick-build--solve the bus problem. There are now examples of such configurations with protected bike lanes on Telegraph in Oakland, Middlefield in Redwood City, or even in the historic core of downtown San Jose itself, as seen below in this shot from 2019 (Swaminathan reports that many of these installations have been removed):

As to the new project on Hillsdale, even if San Jose DOT didn't want to deal with the political issues of removing street parking, there was another option. "They could have done what you see on 10th and 11th, with a slow moving lane just for residents and cyclists. That's a solution that could work," said Swaminathan.

In that installation, a concrete curb is used to create a frontage, local lane that's shared by cyclists and motorists accessing the block. It's not ideal, but it separates the fastest traffic from people on bikes.

Meanwhile, in San Jose, some 23 different motorists have managed, over the years, to crash into a single house on Jackson Avenue. In Streetsblog's view, handing out reflective vests, painting lines (even in green), and gluing down more plastic posts is ridiculous given the typical width and designs of San Jose's streets, all of which encourage speeding and other forms of reckless driving.

San Jose officials need to build proper infrastructure to keep people safe. But that will require removing parking in places. If they aren't willing to do that and provide concrete barriers for bike lanes and intersections, they may as well disband their Vision Zero Task Force.