Amtrak is still struggling to emerge from the worst of the pandemic — and nowhere is it being felt more than on its long-distance service, whose long-distance capacity remains tight even as coastal intercity routes bounce back.

And the problem isn’t just competition from airlines and their comparatively cheap fares. Two derailments in two years have left a mark on Amtrak’s reputation, railroad strikes have nearly furloughed passenger rail nationally, and border closures have severed links to three Canadian provinces, to name just a few of the agency’s news-making challenges.

All hope is not lost for America’s rails, though. Federal and state-level infrastructure investments, a breakthrough court decision, and a new generation of social media savvy rail lovers all promise to bring Amtrak’s long-distance routes onto sturdy footing in coming years — and ridership is already beginning to follow.

Here are three core reasons why long-distance Amtrak routes are having a hard time, and some signs of hope.

An aging fleet

To understand Amtrak’s present requires a little history. When President Richard Nixon signed the legislation that created the quasi-governmental agency in 1970, the Rail Passenger Service Act, he seemingly threw a lifeline to a patchwork of private railroads whose fate had been thrown in doubt by the rise of increasingly-affordable air travel…but in reality, he hoped the whole enterprise would fail.

Nick Stockton of Wired summed it up well:

“[Nixon’s] design approach to Amtrak was mercenary. Nixon had his ombudsman rate the different national route proposals on how likely they were to fail. Then the ombudsman ranked how likely it would be for Nixon to catch the blame for each failure scenario. Nixon didn’t seem to have any personal qualms against passenger rail (at least, Amtrak wasn’t on the enemies list), he just didn’t see it going anywhere. He apparently wanted to expedite Amtrak’s demise so it wouldn’t be a long term burden on taxpayers.”

In the decades since, though, Amtrak has defied the odds, and it even approached the cusp of profitability for the first time in its history in 2019. The fleet it’s running, though, still dates as far back as Watergate — and it’s only getting older.

Marc Magliari — Amtrak’s Senior Public Relations Manager who spoke with Streetsblog while he was aboard an Amtrak train — said that the agency is looking forward to more Siemens ALC-40 Charger series engines hitting the tracks over the coming years. It’s also ordered over 100 Charger locomotives, which began service earlier this year and are far more fuel efficient than the Genesis series.

“They’ll be new and under warranty,” Magliari noted excitedly.

An aging workforce

Amtrak, of course, is going to need a lot of workers to staff and operate all those new trains — and they might be harder to find if the national labor shortage drags on. Since the onset of the pandemic, Amtrak has shed over 1,500 employees from its 20,000+ person workforce.

Magliari explained that a significant portion of Amtrak’s workforce is retirement-eligible, or close to it, meaning the agency will have to act fast to hire and train legions of new employees. At the moment, it’s looking to hire about 4,000 or more new employees.

To help them get there, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded Amtrak $8 million to launch large-scale mechanical training programs, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has money earmarked to mend the personnel shortage. Advocates are hopeful it’ll be enough to keep the trains running.

Track ownership

Pretty much every long-distance rail passenger has at least one story about her train stopping out of the blue — sometimes for multiple hours. That inconvenience, though, often has less to do with Amtrak itself than the private freight rail companies who lease usage rights to the agency and maintain a right-of-way over passenger trains.

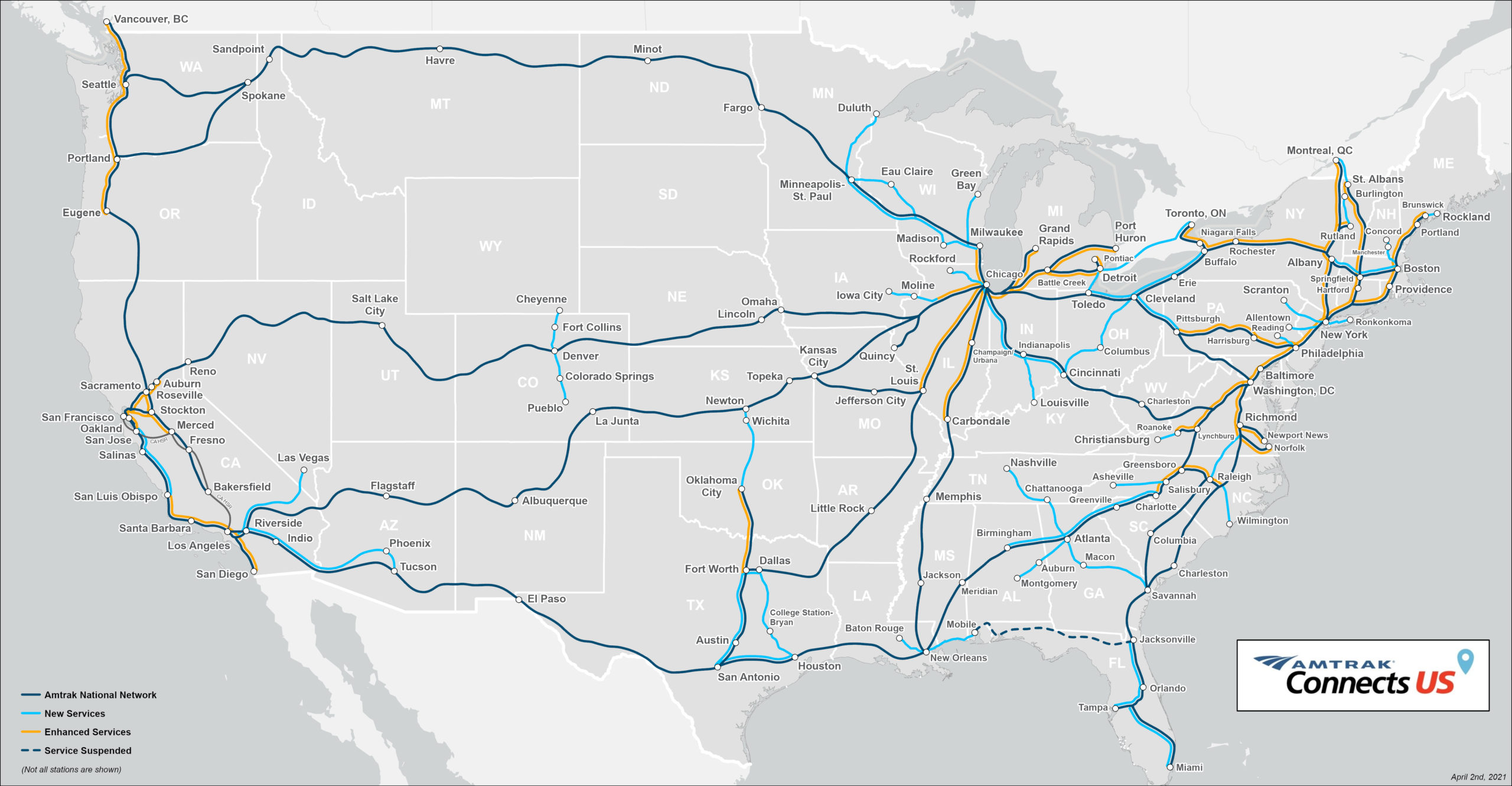

Magliari explains that while Amtrak’s entire network has a footprint of over 21,000 miles, the agency only owns about 620 route miles of that track, the vast majority of which is located in the Northeast Corridor. On a network where much of the railroad is single-tracked, this can mean serious delays if even a single freight train needs to pass an Amtrak vehicle.

Litigation between Amtrak and the Association of American Railroads — a trade organization representing the freight railroads from which Amtrak leases — almost made its way to the Supreme Court in 2019. Thankfully, the justices declined to reconsider the decision of a lower court that effectively allows for the passenger rail outfit to sue freight railroads for violating its right of preference.

Magliari expressed muted optimism about the decision, saying he was glad that Amtrak’s scheduling now “has teeth.” And as for whether it will impact on time performance going forward, his answer was also muted: “We’ll see.”

A New Chapter

Nixon may have thought he was euthanizing the railroads by creating Amtrak, but half a century later, it’s obvious that he underestimated the practicality and the appeal of America’s passenger trains. And today, a certain young man from Delaware who was elected to the Senate just two years after the Rail Passenger Service Act was signed into law is positioned to deliver Amtrak its biggest breakthrough to date.

In one of his most consequential accomplishments as president, Joe Biden guaranteed $66 billion in federal funding to America’s railroads via the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This money will touch just about every inch of Amtrak’s web of operations, including Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) funds designated specifically for service enhancement and research to reactivate defunct and underutilized segments of the network.

The Sunset Limited route, for example, currently only runs three times per week between New Orleans and Los Angeles by way of Houston, San Antonio, El Paso, and Tucson. The Cardinal is another three train-per-week service connecting Washington, D.C. and Chicago by way of Indianapolis, Ind. and over a dozen Appalachian communities between Charlottesville, Va. and Cincinnati, Ohio. Making these routes (and others like them) more frequent would bring enormous change to the communities they serve, not to mention the nature of Amtrak’s long-distance services itself.

The road to a profitable, efficient, and relevant Amtrak may be long and bumpy. Still, all signs point toward a bright future for long-distance trains, bolstered by a young and growing fan base that Nixon never dreamed of.

John Besche is a DC-based writer who reports on religion, urbanism, the confluence of the two, and a little bit of everything in between. He holds a degree in Urban Studies from Yale University. Follow him on Twitter @JohnBesche.