Simple messaging changes can help transportation leaders win over residents who are skeptical of automated enforcement, a new study finds — and there's even more they can do to make those programs equitable, effective, and deserving of public support.

In a recent survey, a team of academic researchers asked 1,500 U.S. adults what they thought about camera-based traffic policing as it exists in their neighborhoods today, and test-drove an alternative framework that they hoped that would earn more support for the controversial policy.

Decades of evidence that technology like speed cameras reliably reduces car crashes on the corridors where they're sited — not to mention their potential to reduce dangerous encounters between BIPOC and human officers — but automated enforcement has become a flashpoint for legal and cultural battles across America. Today, roughly two-thirds of U.S. states don't allow speed cameras at all, while the one-third that does usually restricts the use of cameras to limited circumstances, such as near schools.

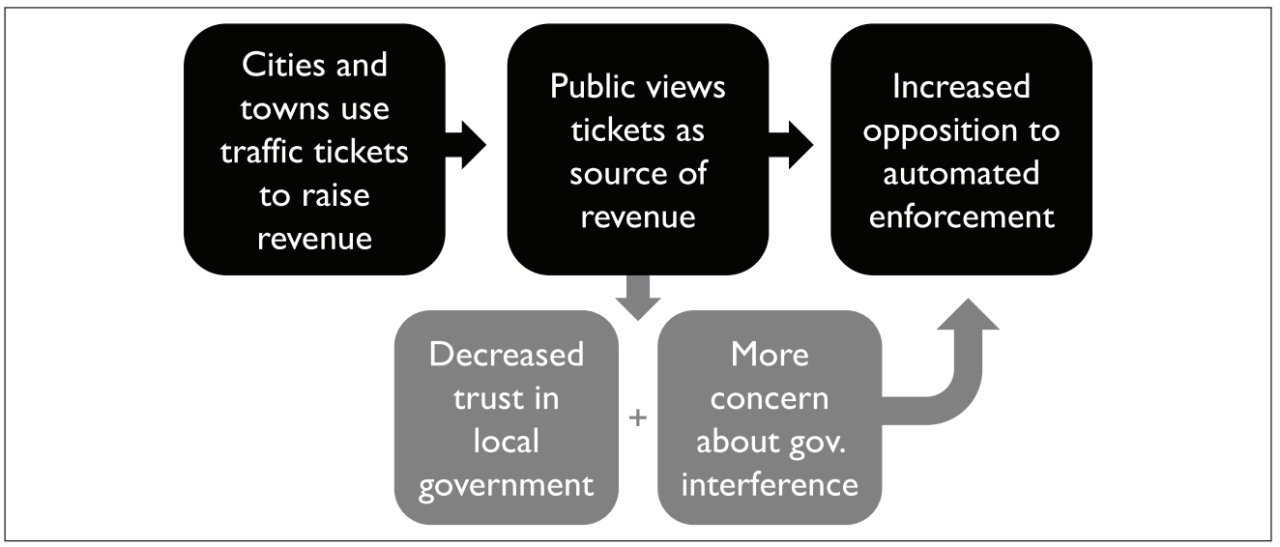

"Transportation safety folks have been banging our heads against the wall for what feels like decades trying to convince the public that automated enforcement is a good idea," said Kelcie Ralph, associate professor at Rutgers University and the lead author on the study. "People tend to say, 'This isn’t about safety; it's about raking in the cash.'"

A majority — 60 percent — of respondents shared that view, saying that automated enforcement was "mostly about raising revenue."

In some U.S. communities, that belief is justified, but also misdirected: A comprehensive literature review that accompanied the study, the researchers cited evidence that many municipalities do over-rely on traffic fines to make up for budgetary shortfalls, with more than 80 local governments of all sizes sourcing at least half of their revenue directly from law-breaking drivers — whether they're captured by cameras or flesh-and-blood cops. Cities with larger Black populations raise more money per capita from traffic violations than cities that are disproportionately White.

Ralph and her colleagues still believe, though, that automated enforcement can make streets safer and more equitable — if cities make structural changes to ensure that it's used to its highest potential as a life-saving tool.

Here are four key recommendations.

1. Use good messaging to bust myths

Despite evidence that traffic enforcement in general is being used to line city coffers, automated enforcement specifically isn't a very good cash cow — because local motorists quickly warn each other of the location of new stationary cameras and drive more carefully when they're nearby.

A 2017 study of New York City's automated enforcement program, for instance, found that only 20 percent of motorists that received a camera-issued ticket got a second one, and that total ticket volumes dropped a shocking 98.9 percent in the first year and a half of the initiative.

If the public knew stats like that about their local communities, Ralph and her colleagues argue, they might view something as humble as a red light camera as a powerful machine to fight government corruption, rather than a trap to steal their hard-earned money. And they even piloted a handy script to get that counterintuitive message across.

Here's an excerpt:

The purpose of [automated enforcement] is to improve safety, not catch unsuspecting drivers. With cameras, politicians cannot ramp up enforcement to raise revenue. In fact, camera revenues fall over time because repeat offenders are rare.

That language seems to have worked: respondents who read it before answering the other questions in the survey were an impressive two-and-a-half times more likely to express support for automated enforcement than those who were shown a control text that wasn't explicit about the benefits of well-deployed cameras.

2. Be careful with camera placement

Just because motorists are unlikely to get a ticket from the same camera twice, though, doesn't mean that they'll be exactly thrilled to get a first one — especially if the location of that camera feels more sneaky than safety-minded. And many of the study's respondents made that known in the survey's comment section.

"People were, understandably, frustrated when cameras popped up at places where the speed limit had recently changed, or at the end of a steep hill or, right at the edge of a school zone," Ralph said. "Instead, we think they need to be in places with known safety risks, and it should be a data driven process."

3. Set appropriate fines — including for the rich

Ralph acknowledges that placing traffic cameras where they'll have the greatest data-backed safety impact could lead to a lot of automated enforcement in communities of color and low income, where decades of racist and classist transportation policies have resulted in high concentrations of dangerous roads and reckless driving, as Streetsblog NYC reported earlier this year.

Whether or not that'd be a good thing, though, is a topic of hot debate among sustainable transportation advocates — especially considering the crushing burden that even the lightest traffic fines can place on people who can't afford to pay.

Or, as one of the survey respondents' elegantly put it: "When the solution to a crime is fine, then the only real crime is being poor."

To make sure cameras don't simply replicate the inequities of in-person enforcement, Ralph and her colleagues recommended that cities explore more progressive strategies, like taking jail time off the table for failure to pay, scaling fines to income, or replacing initial offenses with written warnings or a safety training requirement.

For the most egregious repeat offenders, though — which one survey respondent referred to as people who are "essentially paying to get permission to break the rules" — the authors recommended following best practices from other countries, where proven problem drivers eventually lose their licenses or have their vehicles impounded.

4. Spend most revenues on self-enforcing streets — not cops and contractors

At the end of the day, perhaps the best way to convince the public that traffic cameras are a great safety tool instead of a cash grab is simple: use the money they generate to build things that might someday make traffic cameras unnecessary.

The researchers emphasized that self-enforcing infrastructure — think narrowing roads to make it physically challenging for drivers to speed, even if no one's watching — are among the best uses of traffic fines, while some survey respondents said that public transit agencies and low-income housing initiatives (especially in walkable neighborhoods) also deserve a cut.

The study authors also discussed some of the worst ways to use camera revenues, many of which are, unfortunately, still common in U.S. cities today. Chief among them were extractive contracts with private firms that take home a hefty percentage of fines and sometimes a bonus per violation, creating an incentive to keep the dangerous drivers rolling in a way that charging cities a flat fee doesn't. Such contracts have been involved in prominent lawsuits against automated enforcement programs, and the practice continues today in communities across the U.S.

Other comments from the survey respondents made the researchers question whether even police should be paid to run automated enforcement programs, or whether there should be a cap on how much of their budgets can be sourced from camera revenues. One alternative, the researchers suggest, might be to hand control over to transportation departments, who are better equipped to analyze footage of motorists' bad behavior in a holistic way — and possibly, use that data to recommend infrastructural countermeasures that might deter dangerous driving before they get caught in the act again.