When is a plan not a plan? When it’s “a policy foundation… [with] no… specific projects.”

But to tell this story, step into a time machine.

A long time ago, a bunch of folks (nearly all white men) in closed-off back rooms drew lines on maps. They made plans for freeways, homes to be torn down (nearly all in Black and Latino neighborhoods), parking, suburbs, street widths, etc. When many families protested that they didn’t want their homes torn down, the highwaymen largely responded, “You’re too late, it’s in the plan, and the plan is already approved.” This sort of planning had its U.S. heyday in the mid to late 20th century, from the 1940s through the ’90s or so. The reliance on approved plans to demean community opposition extends to the present day. Back in 2020, for example, the CEO of Metro claimed that Metro had to tear down hundreds of homes to widen freeways through Downey and Santa Fe Springs, because freeway widening “improvements” had already been approved “about three decades ago.”

States, counties, and cities used to make transportation plans, then they used to implement them. Because that’s what “plan” means.

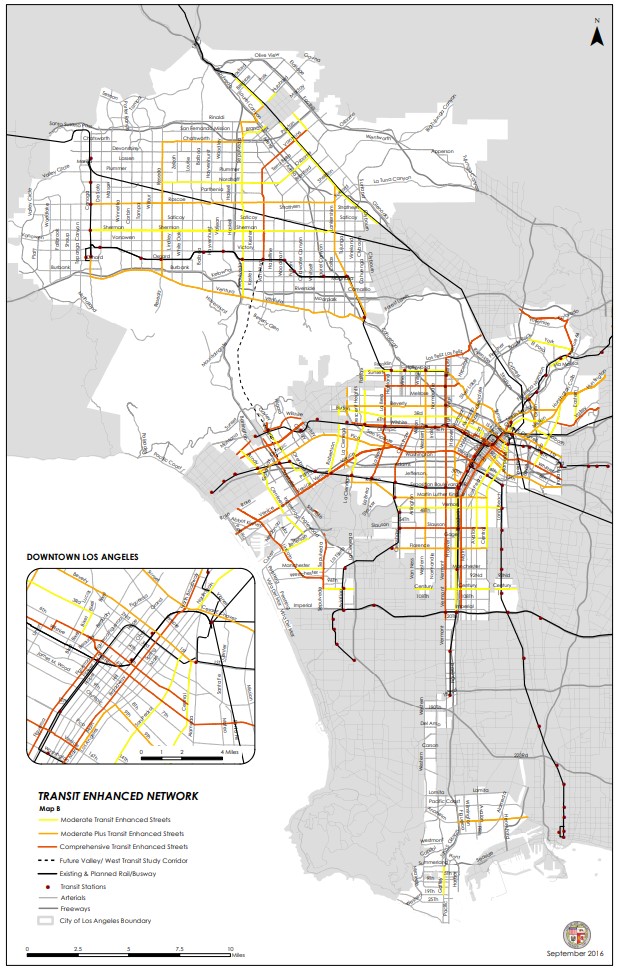

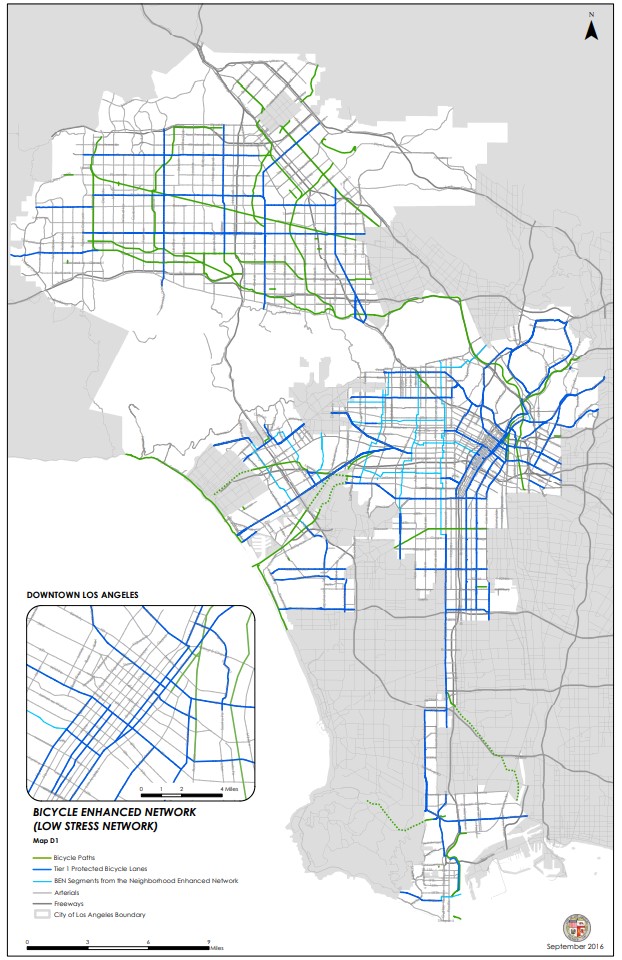

Jump to the more recent past, circa 2014-2015. Advocates fought tooth and nail to get the city of L.A. to make plans for a multi-modal city, with debates now focused on the kinds of lines drawn on the map – e.g. where bus lanes, protected bike lanes, and pedestrian priority zones would go. The city approved the plan, called Mobility Plan 2035, in 2015 and the approved it again in 2016 (because pro-car folks sued to cancel the original approval).

Now jump to the present day. As of 2022, seven years into a 20-year plan, the city has only implemented three percent of MP2035.

So, a coalition (led by Streets for All and including some of those same advocates that fought to get bus/bike/walk stuff into MP2035) decided to get the Healthy Streets L.A. initiative on the ballot in order to force the city to gradually implement those lines on the MP2035 maps. HSLA got the required signatures, and will appear on voters’ ballots in 2024.

A push to get HSLA approved outright resulted in the L.A. City Council entering a “look busy” phase.

Some promising concepts have come out of this phase. The council has affirmed that MP2035 implementation has been crappy, and that future mobility projects need to advance equity by centering investments that serve underserved communities.

But what has been disturbing has been the city’s wholesale backing off of the Mobility Plan as a plan. Instead city staff – from the Planning Department, Chief Legislative Analyst, Department of Transportation, and others – are casting doubt on the city’s approved plan. This occurred repeatedly in an October 6 CLA memo and a November 30 City Council Public Works Committee meeting [audio] discussing the city council’s alternative version of HSLA.

CLA staff repeatedly characterized MP2035 as just “a policy foundation,” “a working guide,” “not an implementation tool with specific projects,” and “street segments indicated on the network concept maps represent potential opportunities.” (emphasis added).

And what about the Department of City Planning? If anyone believes that plans are actually plans, it should be the planners who wrote the plan, right?

At the committee meeting, DCP Planner Emily Gable stated that MP2035 is “guidance” for a “general vision.” MP2035 network maps are “guides for decision-makers.” She called the plan “aspirational” and emphasized its “flexibility.”

It’s instructive to note the pernicious double standard of how the city is treating other aspects of the Mobility Plan.

Bus lanes? Guidance.

Bike lanes? Policy foundation.

Safe walking? Aspirational.

Car capacity? Build it exactly as the plan specifies.

In addition to the multi-modal stuff, MP2035 mandates hundreds of miles of street widenings. There are a bunch of color-coded lines on maps that correspond to just how wide streets should be. Wherever new development takes place the DCP requires developers to spot-widen streets.

Nobody in the city, especially the DCP, is saying that the city should back off on street widening approved in the Mobility Plan. They refer to the Mobility Plan, and use is a rule to tell developers exactly what is required of them.

(There is a motion that proposes ending L.A. spot-widening. Perhaps developers could end widening even sooner by letting city reps know that those street widening specifics are just aspirational policy guidance, no?)

Approved street widening – to increase car capacity – is treated as scripture. Like a… well… plan.

Approved bus, bike, and walk improvements should be afforded the same treatment, not mealy-mouthed excuses.