The future of Bay Area transit service is unclear as local elected officials struggle to agree on a framework for a regional funding measure. Many Bay Area transit agencies are facing large budget shortfalls starting in 2026-2027 when temporary state funding—passed in 2023—will run out. A Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) special committee is tasked with creating a plan for a regional ballot measure that would fund transit service, but their last meeting ended in deadlock.

In order for the MTC or another regional body to put a measure on the ballot they need authorization from the state legislature. Earlier this year Senators Scott Wiener (San Francisco) and Aisha Wahab (Fremont) introduced SB 1031 to authorize MTC to put a nine-county regional measure on the ballot as early as 2026, but in May it was pulled by the authors due to the lack of regional agreement.

In response the MTC set-up a “select committee” to create a framework for a bill to be introduced in 2025. The select committee, which includes elected officials from each of the counties alongside business, advocate, and labor stakeholders, kicked off their work in June with the goal of meeting once a month until October. At their meeting on September 23rd they took a strawpoll on two possible scenarios. On average both scenarios ranked between “neutral or abstain” and “disagree but will go along” and reflected a large divide between members. In response commissioners asked the transit operating agencies—led by BART—to present a proposal at the final scheduled select committee meeting on October 21st.

There are three interconnected variables at issue in the development of the framework: the revenue source and size, the spending plan, and the number of counties.

Revenue source and size

In order to maintain and improve transit service the measure needs to raise around $1.5 billion a year over the nine-county region. Since the funding is needed for operating service, not capital infrastructure, it can’t be raised from a bond. The initial plans for the authorizing legislation in 2024 had a list of revenue options including sales tax, per-square-foot parcel tax, payroll tax, and means-based income tax. The income tax was taken out of the draft legislation, with the explanation that it faces significant opposition from the legislature and governor.

Sales taxes face opposition from community and equity organizations because they are regressive and are already used to fund transportation. County transportation agencies are concerned a new transit sales tax will impact their ability to renew existing sales taxes that support all types of transportation projects. The expiration date of existing transportation sales taxes range by county from as soon as 2030 in Santa Clara to 2053 in San Francisco.

Parcel taxes can be a flat amount per parcel or a set amount by something other than the value of the property, for instance square footage of developed space. At the latest select committee meeting the MTC staff recommended taking a parcel tax out of consideration because it would compete with a property tax for a regional affordable housing bond measure. (The housing measure was planned for the November 2024 ballot, but pulled at the last minute; it is unclear when it will be on the ballot.)

Payroll taxes are used to fund transit in New York City and in Oregon. The rate could vary by the size of the payroll or exempt smaller entities. The Bay Area business community is expressing opposition to a regional transit payroll tax, regardless of the size, because they fear it will open the door to future regional payroll taxes.

The spending plan

Transit needs a sustainable long-term funding source for service. Some revenue lost during the pandemic will likely return over time, but with an increase in remote work it is unlikely that Caltrain’s and BART’s farebox recovery will return to their pre-pandemic levels; Muni’s fare and parking revenue might continue to lag. At the same time transit operating costs—including the need to raise wages to compete in the labor market—are increasing with inflation.

In order to address the competition with county transportation sales taxes, MTC staff has proposed spending plans where the amount dedicated to transit operations decreases over the life of the measure and the money reverts to the counties to replace their existing sales taxes. Transit agencies worry this will make it harder to pass another funding measure in 15 years when they are no longer getting dedicated funding from this measure and still face a deficit.

During the pandemic MTC and the transit agencies created a Transit Transformation Action Plan to improve transit to win back riders and make the regional system more integrated. The programs in the plan are also potentially good selling points with voters at the ballot box. They include investments in fares (transfers, low-income fares, regional passes), transit priority (projects to get transit out of traffic), wayfinding (similar transit signage), and access for people with disabilities. It is proposed that 10 percent of the measure be used to fund these regional programs. This money could also be used to fund new regional services being identified by the MTC currently in their connected network planning process.

A sticking point in the discussions at the MTC continues to be local elected officials wanting to make sure their county gets back benefits that correlate with the amount of funding their county contributes in taxes. There are many local benefits of a well functioning regional transit system, but it is hard to quantify them at the county level in a single agreed upon metric.

Number of counties

A fully regional (all nine counties) measure could raise enough funding to maintain and increase transit service and fund the regional programs. But not all of the counties have the same immediate needs, leading to different priorities by local officials.

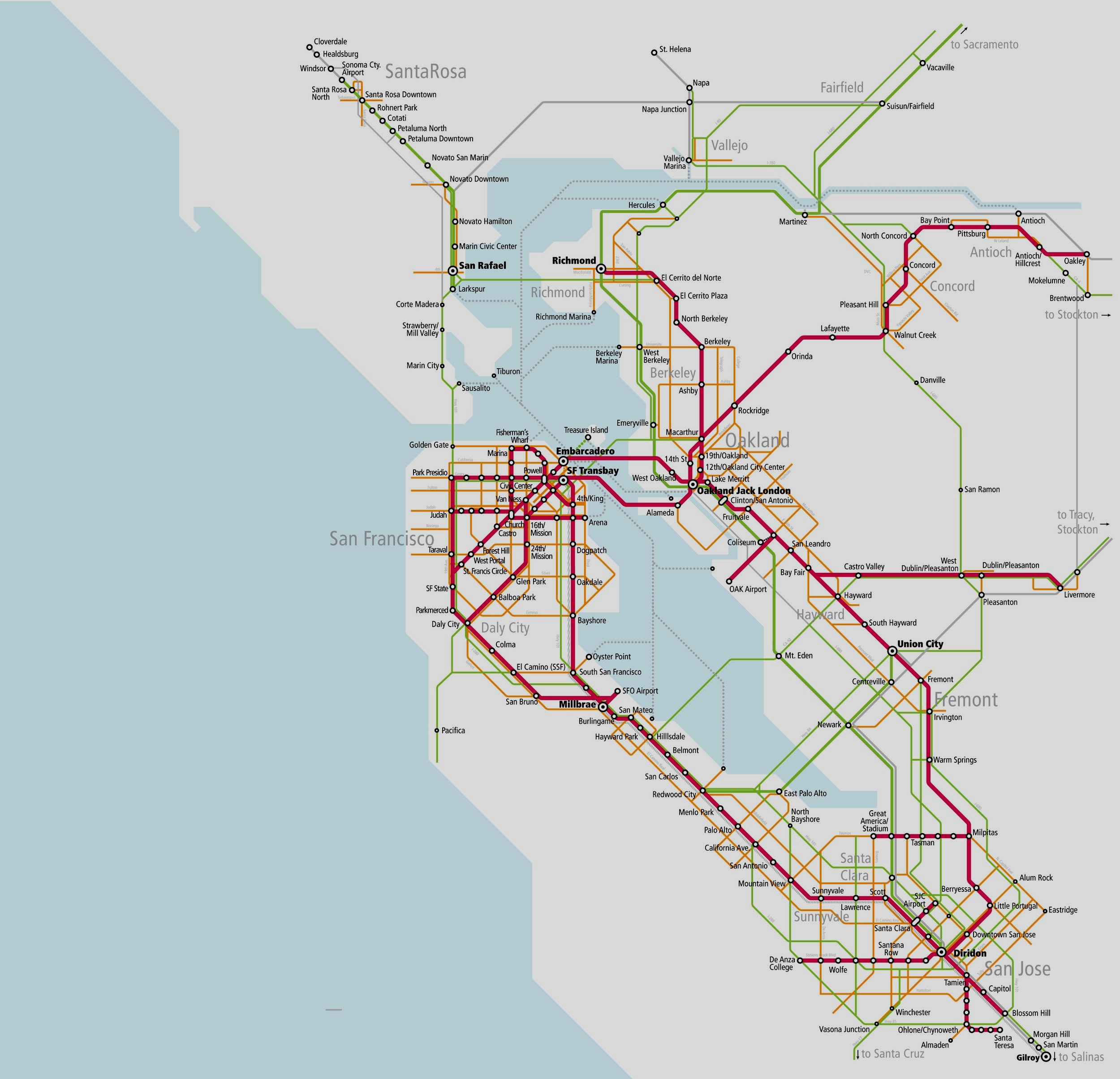

The biggest immediate transit operating deficits are for transit agencies serving Alameda, San Francisco, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties (BART, Muni, Caltrain, AC Transit). Santa Clara county has expressed concern over taxes collected in their county being used to fund transit in San Francisco (the county with the largest need and the most transit trips). Santa Clara has an existing agreement to pay for their share of BART and indicated they are willing to pay for their share of future shortfalls for Caltrain. The Santa Clara transit agency (VTA) doesn’t have a current deficit, but they do have lower service levels per capita than in San Francisco and the East Bay. A regional measure could fund service increases.

Sonoma and Marin agencies are facing fiscal cliffs, but for different reasons. Golden Gate Transit hasn’t recovered all their bridge toll funding and the one-fourth cent sales tax for the SMART train needs to be reauthorized within the next four years. The SMART measure failed in 2020 so there are concerns about competition with another measure. However, it could be incorporated into a regional measure that could benefit more voters. The North Bay counties also have limited local service and need better regional transit connections across the Richmond bridge and Highway 37.

The back-up plan is for multiple measures. This would create additional challenges since people and agencies cross county boundaries. If each county ran their own measure, BART could end up with funding from a subset of the counties it serves and service doesn’t stop at county lines. If each transit agency ran its own measure, voters in San Francisco could be asked to vote for funding for BART, Muni, and Caltrain potentially all in the same year. Advocates have termed this solution “the Hunger Games approach,” but transit agencies have started working on their back-up plan in case the regional approach fails again.

Transit is a regional issue. People need to be able to travel across the region and massive service cuts at any of the agencies would impact the entire region, and California, in terms of climate emissions, congestion, and economic opportunity and competitiveness.

Time is running out for the MTC to come up with a framework that has enough regional agreement to pass. The select committee is supposed to provide a recommendation in October to inform a decision by the full MTC board in December. Authorizing legislation needs to be drafted by early 2025 and approved in the 2025 legislative calendar, so a measure can get on the ballot in 2026. To be successful local elected officials need to put aside the “what is best for their community only” mentality and work together on what is best for the collective good.

***

Laurel Paget-Seekins is a Senior Policy Advocate for Transportation Justice at Public Advocates.