Downtown San Francisco is just starting to see an economic recovery, as companies are requiring employees to come to the office again. Now imagine if BART and Muni undercut that recovery by cutting service by 80 percent. What hope would there be for that fragile economic turnaround if people can't get to and from downtown anymore?

That doomsday scenario was outlined by SPUR transportation policy director Laura Tolkoff and director of special projects Annie Fryman during a press briefing Wednesday afternoon on the looming financial crisis facing Bay Area transit.

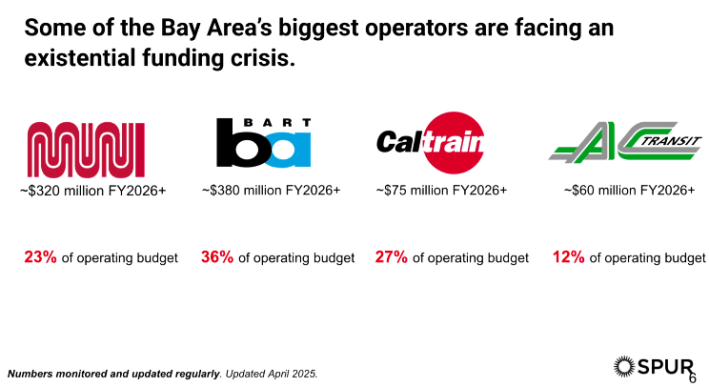

"Some of the Bay Area’s biggest transit operators are facing an existential crisis," explained Tolkoff during the virtual meeting. "For Muni, they're facing a $320 million shortfall starting in fiscal 2026, roughly 23 percent of their operating budget."

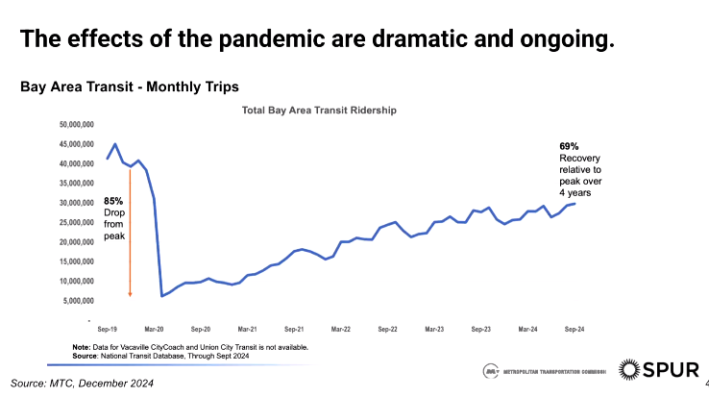

The agencies are in this situation because ridership, while it's been continuing steadily up, still isn't back to pre-pandemic levels. All transit agencies require a mix of state and local funding in addition to fares. Until ridership is fully recovered, state and local entities have to make up for an ongoing shortfall or it will lead to a "vicious cycle," as Tolkfoff put it, of reduced service and reduced ridership revenue. SPUR is working with advocates and lawmakers to try and prevent a "death spiral."

This isn't just about office workers who commute to the downtown core. BART and Muni have actually seen more ridership growth on weekends and evenings as people use transit to get to bars, the theater, restaurants, and museums. Drivers will be hurt from significant transit cutbacks too.

If BART is forced to make these cuts, "expect an extra 12 hours per week in traffic on average," said Tolkoff. "It goes as high as 19 hours from some commutes."

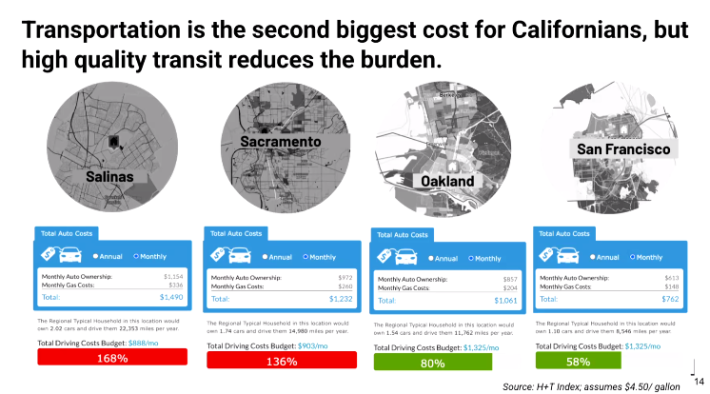

Major cutbacks will have an even more deleterious effect on the poor. "Transportation is the second biggest household cost," said Fryman. "High-quality transit reduces that burden."

Fryman compared regions with quality transit and regions with no transit. "Life without transit is just more expensive," she said. "People will have to spend more money on cars and gasoline."

The Bay Area's notorious housing and inequity problems will just get much worse if it loses good BART, Muni, and Caltrain service, because it will end the possibility of living car-free or car-light, explained Fryman.

So what's the solution to preventing this looming disaster? Fryman explained that BART, Muni and other operators have already worked hard to get more efficient. "Fare evasion is actually 30 percent lower," she said, noting the installation of new fare gates at BART and more fare inspectors at Muni, making sure fare-revenue is maximized.

That means the state and region have to step in with long-term operating funding to BART, Muni, and the others so they can continue to provide a frequent, clean, and reliable service. Lawmakers are working on getting more short-term funding from the state, but ultimately it will depend on SB 63, a transit funding sales tax measure that, they hope, will be on the 2026 ballot. The bill to get it on the ballot, sponsored by Senators Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) and Jesse Arreguín (D-Berkeley), would enable San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa voters to approve at least a 1/2-cent sales tax for transit. San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties might also join the measure.

Ultimately, the hope is to provide even more frequent and reliable service to work with other recovery efforts to bring the city economy back to its pre-pandemic level. "Public transit is the scaffolding for our region," said Tolkoff. "Our fragile recovery is tied to the health of transit."