A SPUR panel to discuss the state's role in funding transit kicked off Tuesday afternoon with a bit of good news—the legislature and Governor Newsom's office announced that they will restore $1.1 billion in cuts from the state budget for transit operations. The state will also provide a $750 million loan to keep BART, Muni, Caltrain, and other agencies moving.

"This is essential bridge funding," said Sebastian Petty, SPUR's senior transportation policy advisor, who hosted the panel. "This will let them continue operating until next year."

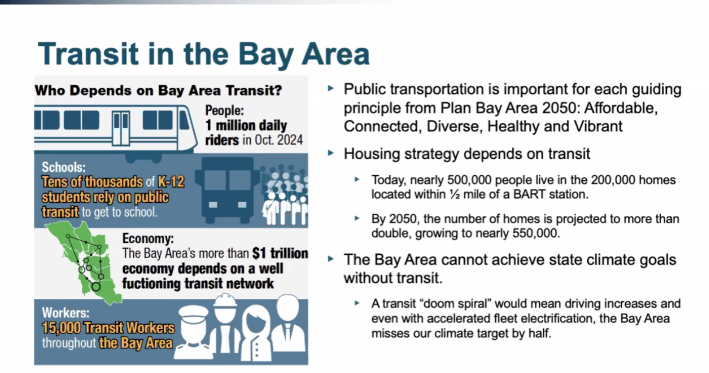

After that, the hope is for a new county-level measure to keep funding BART, Muni, AC Transit, and Caltrain operations, along with other operators in the region. Meanwhile, the state continues to fund seemingly unending road expansions, no matter how pointless. The question is, why is public transportation the forgotten stepchild of state funding, considering its importance to the overall economy?

"We have some champions in the legislature today," explained Michael Pimentel, Executive Director of the California Transit Association, another of the panelists. "But we’re only working with a handful of legislators who will actively go to bat for public transit."

Those names are familiar enough, such as Senators Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) and Jesse Arreguín (D-Berkeley), who are currently working on getting Senate Bill 63 passed, so the Bay Area can implement that sales tax. However, more often than not, lawmakers at the state level treat public transportation as a "subsidized" for-profit enterprise, rather than the essential service it's supposed to be.

"Is it a tool for mitigating climate change? Then the focus needs to be on mode shift," explained Georgia Gann Dohrmann, Assistant Director of Legislative Affairs at the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, and another of the panelists. "But many policy makers want transit to be there as an essential mobility answer for people who don’t have other options, akin to public schools, and libraries... in fact, they want all that, but they also want it to be self-sustaining?"

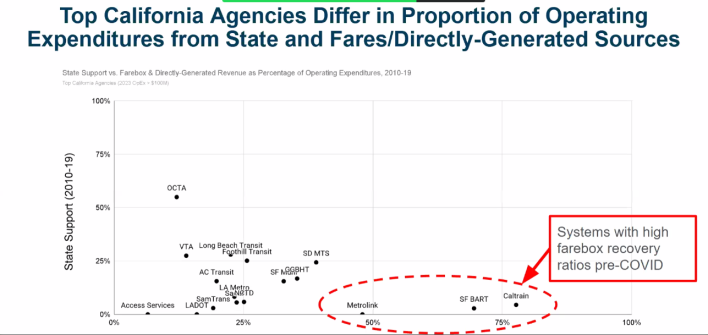

As Dohrmann explained, prior to the pandemic, transit agencies that maximized their "fare-box recovery," and were therefore the least burdensome on state coffers, were praised for their "efficiency." But that meant they geared themselves to downtown office workers. Think BART and Caltrain with their pre-pandemic focus on rush-hour services. Schedules could be as infrequent as once an hour in the evenings after most officer workers were already home.

As seen in the above chart from the presentation, Metrolink in L.A., BART, and especially Caltrain depended on relatively wealthy 9-to-5 commuters to fund operations from 2010 to 2019. Then the COVID pandemic and "work from home" changed everything.

"Systems that were serving a larger share of low-income before the pandemic have recovered more post-pandemic," explained Brian Taylor, Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy in the Luskin School of Public Affairs at UCLA, who was also on the panel. "Commute-oriented operators have struggled to win back more riders." Agencies that were once the considered poorer performers (because they required a higher "subsidy") are recovering more quickly.

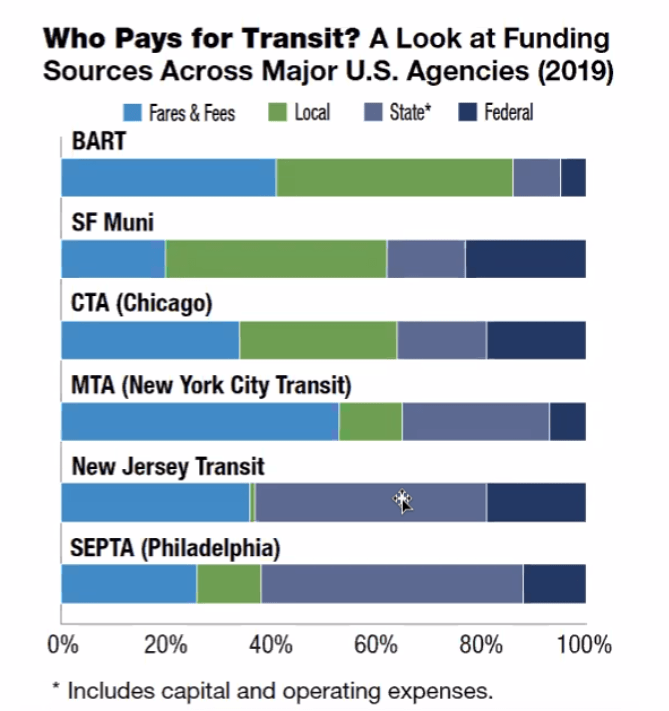

Meanwhile, states such as Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York always took more of a stake in funding transit generally.

"California has traditionally supported transit operators less than other high-transit states," said Taylor. All the panelists seemed to agree that California has to pick up a bigger portion of the bill, because of transit's benefits in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and underpinning so much of the economy. In other words, the state can't keep declaring goals but then not funding the systems that make those goals happen.

The good news, explained Taylor, is that the cities have already invested in building systems. Now they need state help for robust operations to make those systems really live up to their potential. Even if traditionally, it's "...harder to fund operations and maintenance and easier to garner support for major capital projects," he said.

The state also needs to get out of its own way, so lawmakers feel as if they're getting their money's worth. That means continuing to reform the California Environmental Quality Act, so "a single person can't stop an entire project," said Dohrmann. And operators need to keep adjusting service so it's frequent and reliable all day long, to get people on transit for errands, the doctor, or a show. In other words, the days of depending on office-commute trips are over. That's already starting. "Transit operators have done a ton to adjust service levels."

Taylor stressed that cities also need to continue working on ways to increase efficiencies in transit, so the money they receive from the state (and all coffers) goes further. That means more transit-only lanes and signal-priority, so buses (and trains) are more reliable and spend less time stuck in traffic.

He also urged cities to look at the success of New York's congestion pricing, which costs virtually nothing to implement. Cities also need to reform parking rules. "We have to get our arms around the cost of driving, which drivers impose on others," he said. "If we get to a point where we’re managing cars, and taking revenue from it, we’ll have a more stable future; otherwise, we’ll be in this constant struggle [to get funds from the state]."

For more events like these, visit SPUR’s events page.