Japan's famous bullet train, the Shinkansen, carries about 350 million passengers in a year. If a train is a minute late, it's considered a major malfunction. The system has survived several major earthquakes. And it has done all that with "no passenger injuries since it started operating in 1964," explained Tomoyuki Minami with Central Japan Railway Company, during a panel discussion held Friday as part of the American Public Transportation Association's high-speed rail day in San Francisco.

Despite its success, Minami assured the audience of rail professionals in the San Francisco Marriott conference room that they're still working on making things safer. Minami showed a video of a rig the Japanese use to test rail infrastructure. The Shinkansens already have technology that automatically stops trains if a sufficiently large earthquake is detected. Now they're adding guard rails that also assure the trains stay on the tracks as they come to a stop, even in the worst temblors.

Other takeaways from Japan's phenomenal success: "Frequency is actually more important for ridership than speed," said Minami, pointing out that many of Japan's bullet trains have services arriving every minute during peak periods, rivaling most metro systems. Of course, Japan's trains are fast too, regularly operating close to 200 mph.

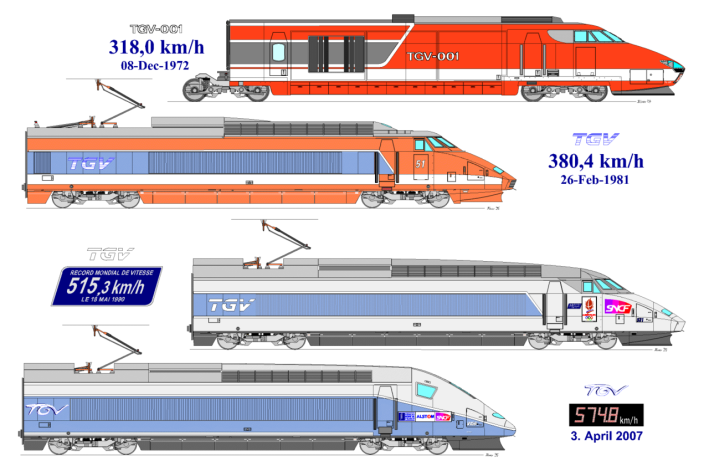

The Japanese presentation was followed by that other country famous for fast trains: France. Since their TGV system started carrying passengers between Paris and Lyon in 1981, they've made a point of holding press events every decade or so to demonstrate new record-breaking trains, shown in the pictogram chart below:

France still holds the speed record for the fastest steel-wheel-on-steel-rail train, a modified TGV that hit 357 mph in 2007.

Alain Leray, President & CEO of SNCF America, talked about the early development of France's TGV. "Back in 1966, [conservative] President Charles de Gaulle had a vision to develop high-speed rail in France," he said, with the "possibility of shrinking France's geography."

Construction of the first TGV set, the TGV-001 pictured at the top of the above chart, was completed in 1972. And while it smashed all speed records at the time by achieving speeds near 200 mph, it had a small problem. In 1973, the Yom Kippur War resulted in a surge in oil prices. When asked to support the construction of France's first TGV line, Georges Pompidou, also a conservative, turned to his rail people and said "it's an electric train, right?" According to Leray, SNCF apparently responded, "of course!"

In reality, the prototype train they'd built was powered by gas-turbine helicopter engines. But the engineers successfully modified the train to run instead on overhead wire (electricity in France is mostly derived from nuclear power). When the initial line was completed and service began in 1981, Leray pointed out that it was with the support of yet another president, François Mitterrand, a socialist. He said that underscores the problem in the U.S., where high-speed rail has gotten politicized, even though there's nothing inherently conservative or liberal about it. "There has to be political will," across the spectrum, he said. "If there had been political will in California, the state would have done something other than Prop. 1A," he said. Prop. 1A, the 2008 measure put before voters in California to build a high-speed train between San Francisco and Los Angeles, only authorized $10 billion, which, even at the time, was only a small fraction of what was required to see the project through.

He also stressed that even by the time France finished its first prototypes, the technology was relatively mature. "Let's not talk about 'innovations.' Just bring the trains to market," he said. And it's because France's TGV was based on conventional rail that it can slow down and use existing lines, immediately expanding the service and providing blended, one-seat rides throughout France. "Interoperability is a must," he said.

That was a point reiterated by Jean-Marc Kuntz, Executive Vice President

Colas Rail, and another of the panelists. He also highlighted the contrast between France's integrated transportation network and the U.S. "I'm living in Strasbourg," he said, describing his trip to California from France. "When I leave my home, I go to the train station and two hours later I'm at Paris Charles de Gaulle airport" (there's a TGV station inside the airport). From there, he transferred to a flight to Los Angeles. And when he landed at LAX, was there a train he could transfer to that would help him get to San Francisco—or anywhere else in the state for that matter? "Well, you know," he said to chuckles from the audience, explaining that, of course, his only options were to rent a car or transfer to another plane (or, yes, take a bus and sit in LA's notorious traffic anyway).

"The point is, you don't need a car on the French side," he explained. In France, high-speed rail is "part of a global system."

Germany, the relative latecomer to HSR on the panel, was represented by Thorsten Krenz, a senior Executive for Deutsche Bahn (DB)'s North America, which is working with California's High-Speed Rail project and planning for its operations. Echoing his French counterparts, he attributes the success of Germany's Inter City Express (ICE), which started running in 1991, to its deep integration with other transportation networks in Germany.

"Lufthansa and DB cooperate. So I can fly into Frankfurt, transfer to an ICE, transfer to a metro or a bus, all on a single ticket, with no car required." In Germany, he explained, "the operators serve the passenger, in the U.S. the passenger has to adapt to the systems." Successful rail systems, he said, "provide door-to-door mobility." That also includes bikes and buses at the stations. Ultimately, he explained, it's not just about high-speed rail tech, it's about "reclaiming time. Travel should not be a stress test." Pursuant to that, he said, American rail development should be focused on getting services going, getting tracks built and station platforms installed, and keeping it as simple as possible. "Not every station has to be the Taj Mahal," he said, stressing, as others on the panel did, that it's ultimately about frequency and interoperability, not tech and flash.

"That's how you turn drivers and flyers into train passengers," he concluded.

The APTA conference continues this week in downtown San Francisco.