Transit advocates have joined a broad coalition of opponents mounting a fight against California Pacific Medical Center's (CPMC) long range development plan for its San Francisco facilities, decrying the significant increase in parking being proposed, and the attendant impact that will have on traffic, transit and pedestrian safety. They argue the increase in parking supply will induce more driving to already crowded streets and will deteriorate Muni service and cause conflicts with pedestrians and bicycle riders.

They also say the DEIR fails to adequately address those concerns, in no small part because the Planning Department's guidelines still don't explicitly correlate parking supply with driving demand, the same argument brought against the City Place mall project on Market Street. Whether the advocates who appealed and are considering a lawsuit against City Place will do the same with CPMC is uncertain, though more will likely be known after the first Planning Commission public hearing on the project today.

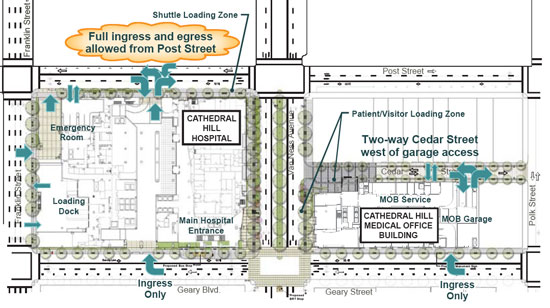

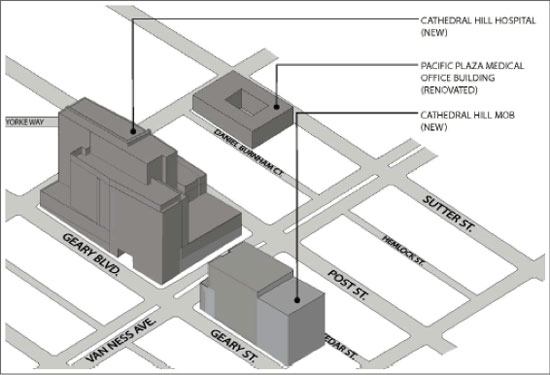

Of the five CPMC locations studied in the DEIR, the most significant net increase in parking will also be at the facility located in one of the most transit-rich and congested parts of the city. The enormous new Cathedral Hill complex will occupy two blocks of Geary Boulevard on either side of Van Ness Avenue, the future crossing point for the city's two planned bus rapid transit (BRT) corridors. During the first phase of construction between 2011 and 2015, when Cathedral Hill will open, CPMC plans to build a 555 bed hospital and a large medical office building (MOB) to complement an existing MOB it owns at 1375 Sutter.

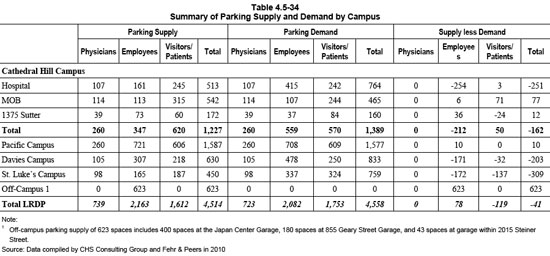

The combined facilities will have over 1200 parking spaces, with a net increase of 650 from current conditions. While the 513 spaces at the hospital are significantly more than code would allow (95 spaces), the 542 spaces at the new MOB are less than half the quantity that the planning code for MOBs mandates, so the MOB will "borrow" from the hospital spaces to make the entire facility compliant within a range that's allowed in code.

The increase in vehicle traffic accessing this facility, advocates argue, will have a tremendous negative impact on those two streets and the transit they carry, as well as numerous other streets and transit lines in the area. The additional parking will increase driving demand, according to Tom Radulovich, Executive Director of the transit non-profit Livable City and one of those who brought the appeal against City Place.

"It's troubling," said Radulovich. "On the heels of City Place, once again we have the SFMTA and Planning Department not sticking up or enforcing the Transit First policy. If you're going to maximize damage to Muni's network, that's where you would do it."

Radulovich argues the worsening of traffic due to the increase of parking is unacceptable. He particularly chastised the Planning Department and argued the Major Environmental Analysis (MEA) division had abrogated its duty to plan for the health of San Francisco's neighborhoods. Instead it was exacerbating traffic delays, inhibiting Muni and failing to adequately mitigate harm to pedestrians and cyclists around the facility.

The DEIR acknowledges traffic will get much worse (see Volume 3, Part 4, Transportation and Circulation) , but CPMC staff argue the only way to construct such a sizable hospital and reasonably expect to accommodate patients, medical staff, support staff and visitors is to build the proposed parking.

Geoffrey Nelson, CPMC's Director of Enterprise Development, said not only were the proposed parking spaces permitted squarely within the Planning Code, if CPMC were building as many spaces it projected it would actually need, the total would more than double. Nelson argued CPMC wasn't basing these numbers on suburban Institute for Transportation Engineers (ITE) estimates, but on extensive data collection of mode choice and trip generation at its other four facilities, which were then projected onto Cathedral Hill.

"We don't wake up and go, I need this much parking. Our calculus that we use is, I have a hospital with 555 beds that has a certain patient volume and has a mix of cases and those patients are seen by a suite of physicians and specialists," said Nelson. "If you look at our existing campuses, we typically have a ratio of twice as much non-hospital space to support hospital space than we have on this campus. This is about as lean as you can go in terms of physicians and specialty clinics and still have a rational availability of specialists to the hospital."

Where Nelson and Radulovich agreed was that the Planning Department's guidelines didn't correlate parking supply with trip generation and driving. "I don't think explicitly there is an assumption that if you ramp up or down the parking that it has an impact explicitly on the analysis," said Nelson. Instead, he noted, as part of the preparation for the DEIR, CPMC ran "sensitivity tests" to determine what level of parking wouldn't have an impact on traffic in the neighborhood.

"If you did half the MOB or half the hospital, would there be any meaningful reduction in peak period trips?" said Nelson. "The answer is basically, you have to get down to such a small, basically less than what the code allows on the site's proposal to really meaningfully reduce peak period traffic impacts."

"The Planning Department is like the White Queen in Alice Through the Looking Glass: 'if you practice believing impossible things, you can get so good at it, you'll believe six impossible things before breakfast.' They've become the White Queen of transportation planning." --Tom Radulovich

For Radulovich, the fact that all the extra parking is code compliant shows the code is out of step with a livable city. "They may be correct in saying this is by right, but that's not to say it's not too much. The whole purpose of the planning profession was to increase people's health and well being, but their planning tools don't account for them and they don't propose any effective mitigations."

Radulovich compared the Planning Department's view of parking with a fantasy novel. "The Planning Department is like the White Queen in Alice Through the Looking Glass: 'if you practice believing impossible things, you can get so good at it, you'll believe six impossible things before breakfast,'" he said. "They've become the White Queen of transportation planning."

Planning Department Director John Rahaim did not respond to requests for comment on this article.

Nato Green, a labor representative for the California Nurses Association (CNA) and a spokesperson for the Coalition for Health Planning, said the Cathedral Hill facility as planned would devastate the neighborhood with traffic. In addition to an array of complaints with numerous other pieces of the plan, Green said the Coalition for Health Planning was concerned with the affect traffic would have on health care delivery.

"There are significant things about the relationship between traffic and health care. The plan is expected to bring an extra 10,000 cars a day. This means that there will be babies born in traffic," he said. Green argued the plan inadequately analyzed how traffic impacts would affect patient transfers, let alone emergency and disaster response. Green said CNA had fought with Sutter Health, CPMC's parent company, across numerous counties in the Bay Area and said their "regionalization" plan was ultimately eliminating 1300 beds across the nine counties, which would require patients not only to drive more, but farther. According to Green, the DEIR scope of study fails to account for the larger changes.

"Are the health care benefits so overwhelming that it's worth destroying the central city and its neighborhoods?" asked Green. "The answer is no."

CPMC's Nelson acknowledged the long-standing riff with the CNA and said unfortuntely the Cathedral Hill hospital plan "hits every [third] rail in San Francisco, there's not an issue this project doesn't hit." Though he wasn't surprised by the initial uproar, he said he thought some of the opponents just wanted to see the project go away. He also defended CPMC's travel demand management (TDM) plan and said they would institute a significant shuttle system linking facilities to BART and other transit hubs with headways under five minute in many cases.

"Would I like it not to be a petri dish around all the issues on parking? I'd love it," said Nelson, but he noted the data behind the parking demand they presented in the DEIR was rigorous and he felt the proposed supply they hoped to build was consistent with their needs.

Both the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), which runs Muni, and the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA), the long term transportation planning body for the city and county, expressed reservations with the project, but resisted outright criticism. Both agencies have worked extensively with the project sponsors and generally felt CPMC was trying to ameliorate its environmental impacts.

"As a Transit First city, we have serious concerns about the project, however, we are committed to working with those involved to ensure that we identify innovative solutions to make this project work for everyone," said Paul Rose, SFMTA's spokesperson. "At this point, we are exploring all options as we move forward with identifying the appropriate solutions."

Tilly Chang, Deputy Director of Planning at the SFCTA, said they had been negotiating with CPMC to make changes to their initial plan to mitigate the impacts the driveway entrances to the MOB and the hospital on Geary would have for the future Geary BRT. In the first iteration of CPMC's proposal, for example, there would have been ingress and egress at both facilities on Geary, but SFCTA and the Planning Department had convinced them to eliminate egress (except for emergencies at the hospital) onto Geary.

"We feel like the on-street design and on-street concepts are getting there," said Chang. "The parking garage is a different issue. We've talked with them about parking and parking provision and they feel like this is what they need."

Nelson was reluctant to hypothesize how much less parking they could build and still keep the facility feasible, but he also expected the project dimensions and attributes to change throughout the approval process. "If we had to reduce the parking somewhat, is there some line that we would cross where we would go, "no más?" he said. "Yeah there is, but I couldn't tell you what it is."

"That said, I've deliberately not put a straw man in there for analysis. We've deliberately put a thoughtful approach for analysis and I hope it's not taken as a throw away option to then get us to some 'real' negotiation," said Nelson. "If there's change to be made, we need to do it on some rational basis."