After four years of an agonizing bicycle injunction that prevented the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) from adding any significant improvements to the city's bike network, a judge earlier this year finally freed the SFMTA to begin building out the city's long-promised Bicycle Plan.

In short order, the SFMTA made some very noticeable improvements, adding protected bike lanes on Mid-Market Street, installing thousands of sharrows on bicycle routes, striping ten miles of new bike lanes in a year and placing hundreds of new racks around the city. However, the game changing transformation that will elevate San Francisco into the upper echelon of world-class bicycling cities has yet to happen.

Those of us on the streets every day know the city can't settle for six-foot lanes that leave cyclists straddling the perils of speeding traffic on one side and car doors swinging open on the other. Why should the only truly dignified bicycling space be a handful of blocks on Market Street, the Duboce Bikeway and the Panhandle? To bring San Francisco up to date with Copenhagen and Amsterdam, or even Portland and New York, the city must embrace the infrastructure that makes those cities safe and inviting to people who ride bikes.

Given how long it took to get this far, you might reasonably wonder if San Francisco will ever get to a point where cycling is a safe mobility option and welcoming for people of all ages. Maybe, though, if you consider the strong advocacy community we have here, elected officials who really do want to change the streets and the projected population growth that will stir a greater demand for bike facilities, it won't take as long as you think.

Perhaps all the city needs is a new bike plan.

In its most ambitious undertaking to date, the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition (SFBC) has launched an initiative it calls "Connecting the City," where bicyclists of any age and ability would be able to comfortably pedal across the city on a network of continuous bikeways from the Ferry Building to Ocean Beach, Park Merced to Downtown or Mission Bay to the Golden Gate Bridge.

"Connecting the City's priority crosstown routes would take routes that are already being used and elevate it to 8 to 80 standards that feel comfortable and inviting for someone who is 8 years old or 80 years old," said Renee Rivera, the SFBC's acting executive director, borrowing a page from Gil Peñalosa.

"Connecting the City's priority crosstown routes would take routes that are already being used and elevate it to 8 to 80 standards that feel comfortable and inviting for someone who is 8 years old or 80 years old," said Renee Rivera, the SFBC's acting executive director, borrowing a page from Gil Peñalosa.

The three crosstown routes in the plan are not a revolutionary idea. Bicycle advocates have been talking about similar concepts for years. This time, however, the SFBC, one of the city's most influential advocacy organizations, is pouring its resources into Connecting the City and luring some of the Bay Area's most talented transportation planners, designers and architects to fashion a plan that would be shovel-ready.

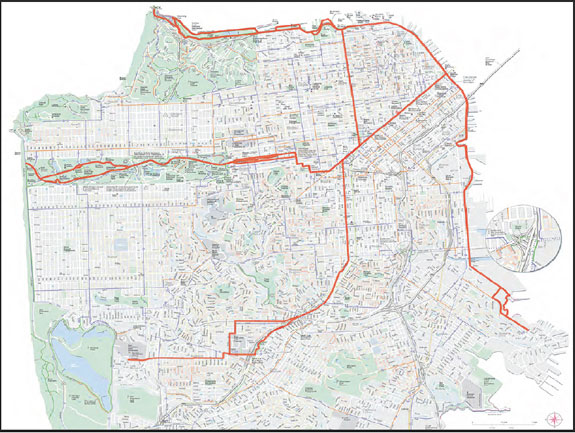

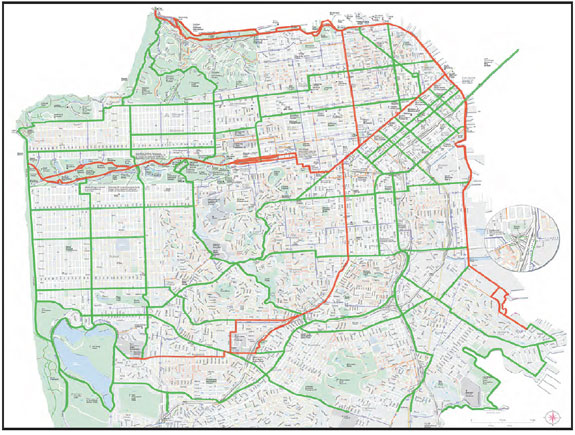

The 27 miles of crosstown bikeways are laid out over some of the city's most important bicycle routes and would connect current gaps in the network. The SFBC is focusing first on getting those priority routes in place within 5 years, but it is also advocating for growing the current 55 miles of standard bike lanes to 128 miles of "next generation" bikeways in 10 years, a dramatic increase reflective of New York City's recent expansion. The early estimate for what the whole plan would cost is about $100 million.

“Peanuts,” said Rivera, when you compare it to the cost of adding transit capacity.

Segments of each route might feature different treatments depending on the neighborhood, but the theme is comfortable and continuous, whether it's a cycletrack with safe-hit posts, a green bike lane along the curb with buffered parking or a bike boulevard. As the SFBC's Andy Thornley describes it, each route must produce the "aaah" effect, the sensation you get when you're liberated from the anxiety of threatening auto traffic.

"Our design vehicle is the 60-year-old woman with two bags of groceries. How does that user look when you set her down on these various points?" Thornley explained during a recent presentation to Streetsblog. Connecting the City, he pointed out, is as much about calming bicycle traffic as it is about calming auto traffic and making the streets more pleasant for transit riders and pedestrians.

"What [San Franciscans] want is a neighborhood where they don't have to live in the back of the house and can live up front, where you can take the dog for a walk and not worry about running across the street," he said.

"This is not just bicyclists advocating for more street space. This is many groups coming together to advocate for a city that's going to work better for everybody," said Rivera.

"Bay to the Beach," "Bay Trail," and "North-South Backbone"

The Connecting the City "Bay to the Beach" crosstown route would provide a comfortable, continuous bikeway from the Great Highway to the Ferry Building, with protected lanes spanning the entire 8-mile route on JFK Drive, Fell and Oak streets and the Duboce Bikeway and Market Street. Parts of the Wiggle may not need separated bikeways, but streets would be traffic calmed. The route would feature a smooth ride for the entire length of Market Street, which is scheduled to be repaved in 2015, and continue through Harry Bridges Plaza to the Ferry Building.

Cars would have limited access to Market Street, transit would run in the two middle lanes and cyclists would pedal along a wide dedicated bikeway with high-visibility European-style treatments at intersections. A multi-modal trip from the Richmond District on the Bay to Beach route might include dropping your bike off at a new bike station near Market and 8th, a former boarded up storefront, and taking BART to work in Oakland.

The 11-mile Bay Trail route would begin in Indian Basin and end at the Golden Gate Bridge. You could start in Hunter's Point and continue on to Hudson Street, the Indian Basin Pathway, Heron's Head Point, Cargo Way, Illinois Street and Terry Francois Boulevard. Crossing the Lefty O'Doul Bridge would be a lot easier thanks to a two-way path that would become a two-way protected bikeway along the Embarcadero. If grandma and grandpa were visiting, you could check out a few bikes from a bike share pod along this route and ride peacefully to a pedestrianized Jefferson Street in Fisherman's Wharf, where you could drop off the bikes near the Hyde Street Pier.

The 8-mile North-South Backbone ride would take you from Park Merced and San Francisco State University all the way to Aquatic Park. The continuous bikeway would run along Holloway Street, Lee Avenue, San Francisco City College, Ocean Street, Balboa Park, Tingley Street, the Still Street pathway, Phelan, Judson, Gennesee, Monterey/Hearst, Arlington, San Jose, 29th Street and Tiffany. When you get to Valencia Street you wouldn't have to worry about double parked vehicles and delivery trucks blocking the bike lane: a protected cycletrack would be installed in the center of the street.

You could then pedal onward to Market Street and Polk Street, where a counter-flow bike lane would take you north on Polk. Curbside bikeways protected by buffered parking would run on both sides of Polk. When you reach Aquatic Park, and want to head toward the Golden Gate Bridge, you'd no longer have to huff and puff your way up the MacDowell Road hill before Fort Mason or to the bridge itself.

One of the signature elements of Connecting the City would be a causeway that would circle around Black Point (see the first image in this story). The Brian O'Neill Memorial Peopleway, named for the late superintendent of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, would set off at Pier 4 and stretch over the water to the old Fort Mason firehouse, akin to Portland's Eastbank Esplanade. The SFBC's Rivera said funding for the bridge could be folded into the waterfront improvements that may come if San Francisco wins its bid for the next America's Cup.

Moving along the route would take you past the Marina, Crissy Field and Fort Point, but what happens when you or your mom needs to climb yet another hill to get to the Golden Gate Bridge? Borrowing an idea from Norway, the SFBC is proposing a bike lift that would take you from the Fort Point parking lot up to the visitor center.

"This is basically using cable car technology but on a smaller scale," said Rivera. "You put your foot on a foot pad and then it goes about three miles an hour and carries you right up the hill."

The three priority routes and all of the city's bikeways would include simple wayfinding signs so any tourist or bicyclist unfamiliar with the city wouldn't need a map to get around.

From Conceptual Design to Implementation

The SFBC has a "plausible conceptual design" for the routes, but Rivera stressed that realizing the vision would take outreach and much more feedback from the public. The organization plans to present more information in 2011, but for now is working behind the scenes to vet Connecting the City with key agencies like the SFMTA, the San Francisco Planning Department, the Department of Public Works, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority (SFCTA) and elected officials.

"We're gathering the input and the conceptual framework and then we're going to be out there meeting with neighborhood groups, with merchant groups and getting that level of input," said Rivera. "I want to emphasize it's not a baked cake. It really is going to be a constant process of refining to make sure that it really does work for everybody."

Wanting to avoid the mistakes of the past, the SFBC is also thinking ahead about the CEQA process, so that projects don't get stuck in environmental review or sidelined in court. Rivera said some bikeways could be done on a reversible trial basis, carrying a much lower environmental review threshold that would also speed the process "because it actually allows you to gather some real data." Another question yet to be decided is whether the majority of projects could also fall within the scope of the current EIR since they are on the existing network.

"I think we're mindful that it isn't just about showing the vision and building the appetite. We really do have to fix the process and that notion that CEQA review is a big challenge," added Thornley. "There's no point in doing something that is going to set us back."

Rivera also hopes an update of federal bike facility standards in the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) will help put Connecting the City and all innovative bike projects on a faster track.

For now, the SFBC is setting a near-term timeline for what's most realistic. For the rest of this year, it will conduct further outreach and identify funding. In 2011, the coalition wants to see trials of innovative bikeways on the ground and "3 miles of continuous 8 to 80 bikeway." By the end of 2012, it wants the city to complete its first crosstown route and reach a mode share target of 10 percent of all trips being made by bicycle.

Though currently 6 percent of trips are by bicycle, Connecting the City would help propel San Francisco toward achieving the SFMTA's 2030 mode split goal of 20 percent of trips by bike.

Supervisor David Chiu, who recently returned from an inspirational trip to Amsterdam, thinks we can do better than the SFMTA's goal. Today, before the SFCTA Plans and Programs committee, he announced the introduction of a resolution[pdf] before the Board of Supervisors that would set a goal of 20 percent of bicycle trips in San Francisco by 2020. Connecting the City, he said, will help get us there.

"If we want to grow as a city, if we want to ever get denser, if we want to protect our environment and make sure that our residents are healthy and make us a more livable city with a higher quality of life, I think this is a goal that we need to adopt," he said.